What Is the UN Security Council?

In this free resource, learn more about the United Nations’ most powerful body working to maintain international peace and security. Explore the security council’s failures and successes, and why the UN Security Council’s veto power is so controversial.

History of the UN Security Council

World War I revealed the terrible consequences of global conflict. No one wanted to repeat its cataclysmic violence.

And so, in the final year of fighting, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson shared his idea for ensuring the world never again descended into such destruction. In a 1918 speech, he advocated for the creation of an “association of nations” that would respect one another’s borders and independence. By 1920, the League of Nations was born.

The league was staked on the idea of collective security, meaning the invasion of one country would be treated like a threat to the entire group.

But the league’s big dreams for world peace crashed into harsh realities. For all of Wilson’s advocacy, the U.S. Senate voted against joining the league. Following World War I, American leaders and their constituents feared the entanglements and obligations of membership. The league’s requirement for unanimous agreement before acting further weakened the organization. In the two decades after its founding, it failed to stop Japan from invading China, or halt Italy from invading Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). Furthermore, the League of Nations was unable to counter the rise of Nazi Germany.

The League of Nations ultimately fell down on the job. However, the organization laid the groundwork for what came next: the United Nations. World leaders created the United Nations after World War II in yet another attempt to promote global security and peace. But for this new organization to succeed, it had to be stronger than its predecessor.

What Is the UN Security Council?

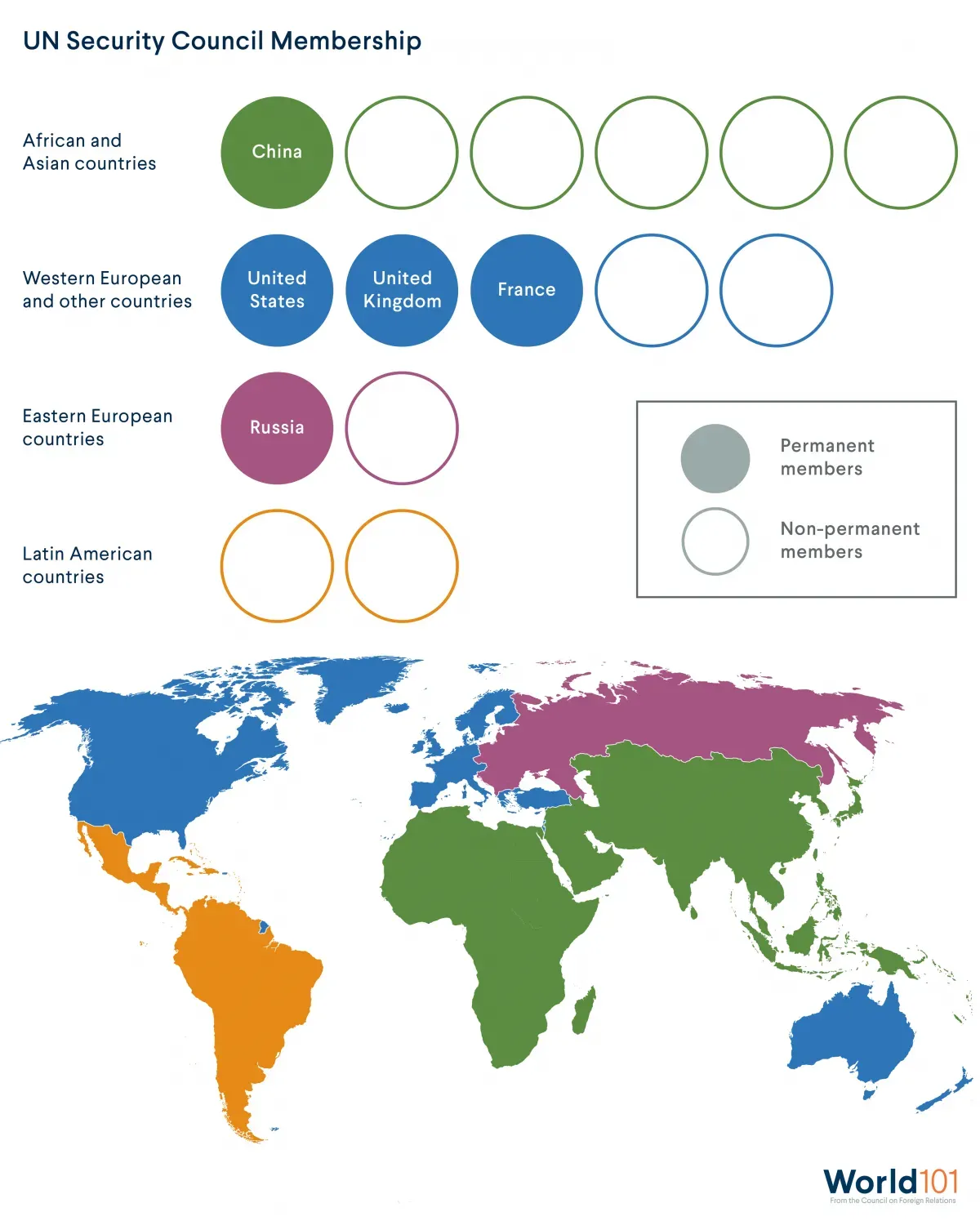

Along with the founding of the United Nations, the UN Security Council was established in 1945. The Security Council is the organization’s most powerful body responsible for maintaining international peace and security. It can issue sanctions and even authorize military force. Five countries—the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom—helm the Security Council as permanent members (known as the P5). In addition to their permanent status, each P5 nation has the power to veto any resolution with which it disagrees. Ten other UN members, each elected for a rotating two-year term and without veto power, round out the Security Council.

That construction tethers decision-making authority to those with significant power in the international system (the P5 members, for example, all hold nuclear power). Though controversial today (see CFR Education’s mini-simulation UN Security Council Reform), the Security Council has persisted since 1945 as a major force in global affairs despite the geopolitical shifts since the United Nations formed.

This resource explores the inner workings of the Security Council. It will examine its successes, its failures, and call for its reform at a time when the P5 no longer reflects the world’s balance of power.

This resource explores the inner workings of the Security Council, looking at its successes, its failures, and calls for its reform at a time when the P5 no longer reflects the world’s balance of power.

How does the UN Security Council authorize action?

International institutions are often only influential when their most powerful members agree to work together. The Security Council, for instance, can’t act when any of the P5 countries uses its veto to block resolutions that threaten its national interests or those of its allies.

However, cooperation between the P5 countries can have significant consequences. Security Council resolutions have legitimized multinational forces defending invaded countries. The Security Council has also supported military interventions to protect civilians from mass violence.

The United Nations can also build and deploy its own multinational military force consisting of personnel, called peacekeepers, supplied by member countries. It has sent peacekeepers to conflict zones to protect vulnerable people. Peacekeepers can also be deployed to enforce cease-fires and safeguard elections, among other missions. Since the United Nations’ founding, over one million peacekeepers have been deployed in more than seventy operations around the world.

To understand more about the variety and record of those operations, let's explore how the Security Council responded to four international crises.

The Korean War

The Security Council can turn the tide of war when it agrees on a course of action.

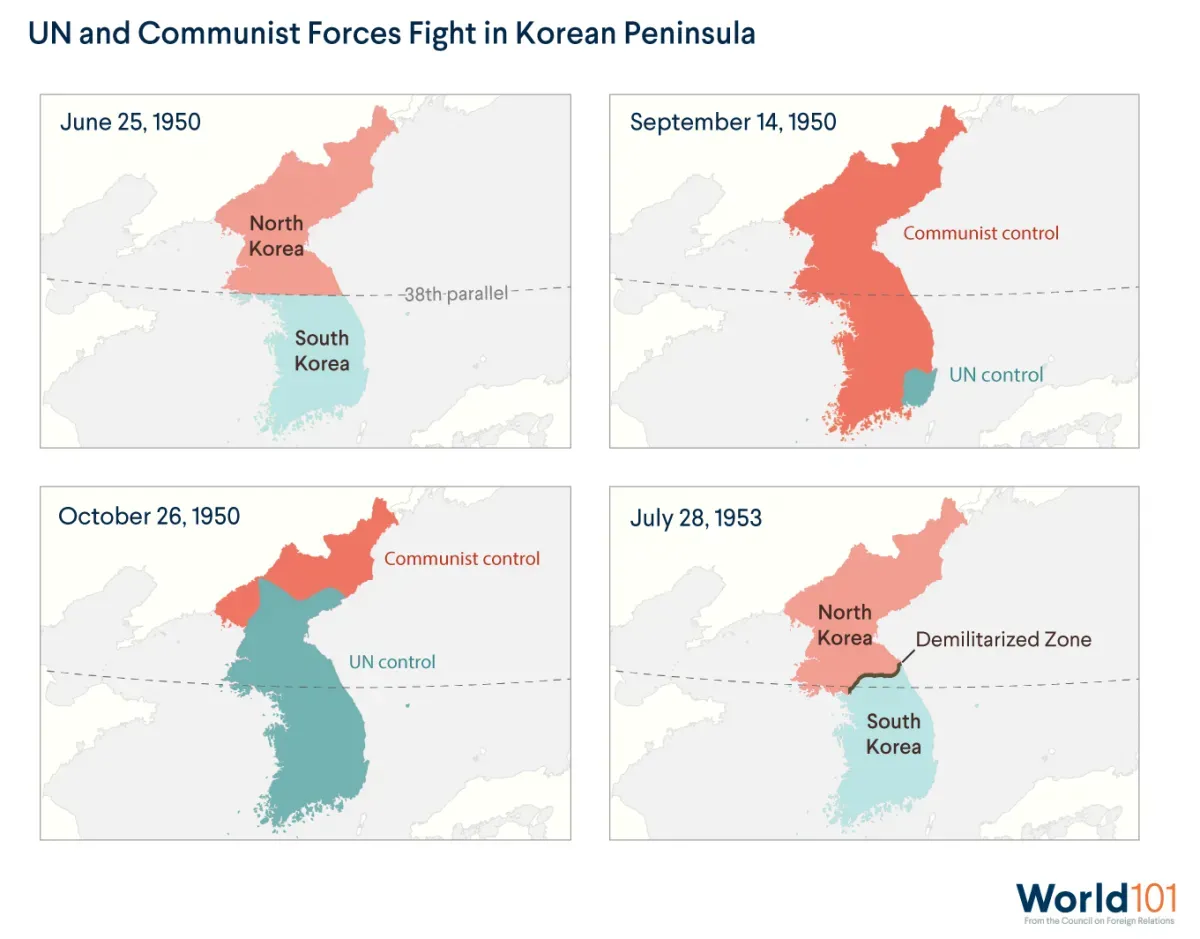

By the end of World War II, Japan had lost most of its colonial empire, including Korea. In turn, the United States and the Soviet Union—victors over Japan—moved in, jointly occupying the Korean Peninsula. They divided the former Japanese territory into two spheres of influence. The Soviets supervised the communist north, the United States oversaw the south, and the boundary known as the thirty-eighth parallel divided the peninsula.

But that line was not to hold. In a bid to unite the Koreas in 1950, North Korean Premier Kim Il-sung sent North Korean troops south with Soviet and Chinese backing. Just three days later, North Korean soldiers seized the South Korean city of Seoul.

When news of the invasion reached the United Nations, Secretary-General Trygve Halvdan Lie reportedly said, “This is war against the United Nations.” At the urging of the United States, the matter was brought before the Security Council. However, the young organization was already roiling with controversy. China had recently undergone a communist revolution but was represented on the Security Council by a government that had been exiled to Taiwan. In response, the Soviet Union was boycotting the Security Council. The Soviets were outraged that China’s communist government did not occupy the Security Council seat.

With the Soviet Union abstaining, the Security Council authorized force to counter the North Korean invasion. A UN command furnished with multinational troops led by the United States soon made its way to Korea. After back-and-forth advances, three years of fighting ended in a stalemate, with a demilitarized zone at the thirty-eighth parallel. To this day, the United Nations monitors the area.

The Invasion of Kuwait

One of the Security Council’s top responsibilities is to protect the sovereignty of the United Nations’ members.

After Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990, U.S. President George H.W. Bush announced that Iraq’s aggression would not stand.

What followed has been hailed as a high point for cooperation among the Security Council’s P5. The UN response to the invasion of Kuwait is an example of how the governing body can effectively advance collective security.

With the United States playing a leadership role, the Security Council passed several resolutions imposing economic sanctions on Iraq. The United Nations also set a deadline for Saddam’s forces to withdraw from Kuwait. After Saddam refused to comply, the United States spearheaded a UN-approved air and ground campaign comprising around 750,000 soldiers from dozens of countries. The goal of this operation was to push back Iraqi forces and restore Kuwait’s sovereignty. Working through the United Nations provided legitimacy to the military intervention, helping the United States drum up support from Congress and its international partners.

After just seven weeks, Bush announced that the multinational coalition had liberated Kuwait.

Kosovo

The Security Council does not always agree on how to respond to crises. In such instances, countries often seek action from other multilateral organizations—as was the case in Kosovo in 1999.

At the time, Serbia controlled Kosovo, but calls for independence were stirring among the region’s ethnic Albanian population. Serbian authorities responded with violence—even threatening ethnic cleansing.

The Security Council instituted an arms embargo. However, Russia and China threatened to veto any authorization of military action. With the Security Council gridlocked, the United States and its allies staged a humanitarian intervention through a security alliance known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The NATO intervention pushed the Serbians to negotiate an end to hostilities. But the campaign also lacked UN authorization, violated Serbian sovereignty, and caused widespread damage and displacement. The humanitarian intervention also contributed to thousands of deaths and the displacement of over a million Kosovar Albanians. NATO’s action revealed that countries can take many approaches to address international crises—with or without UN approval.

Peacekeeping in Haiti

The Security Council can also pass resolutions, when nine or more members vote to pass a measure and no P5 member vetoes it, to establish peacekeeping operations in places where it sees threats to international peace and security. However, sending in peacekeepers—also known as the Blue Helmets—has a mixed record of success. On the one hand, experts suggest UN operations lead to shorter wars and fewer civilian deaths; on the other, such interventions do not stop civil wars from reigniting. More often than not, peacekeepers can do little to lessen violence in conflict zones.

In 2004, the Security Council voted unanimously to authorize a peacekeeping mission in Haiti amid violence and political turmoil. More than eight thousand UN troops, police, and other personnel moved in. The mission’s goals included political stabilization, disarmament, and police reform. But serious problems—including reports of UN personnel committing sexual violence—plagued the mission. Additionally, after a 2010 earthquake killed hundreds of thousands of Haitians and further destabilized the island, an outbreak of cholera spread, likely from a contingent of peacekeepers. Thousands of people perished from the disease.

The United Nations had originally authorized a six-month mission, but the intervention lasted thirteen years. (The United Nations concluded a follow-up mission in Haiti in 2019.) Haitians’ experience under the mission reveals how the Security Council’s decisions affect ordinary people. The impacts of UN intervention are especially felt in developing countries—and not always for the better.

The Pros and Cons of the UN Security Council Veto

Since the United Nations’ founding in 1945, P5 countries have cast approximately three hundred vetoes. These votes have prevented the institution from acting in many politically charged crises.

The United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom cast vetoes at different rates and for different reasons. Russia (formerly the Soviet Union) has cast nearly half of all vetoes in the United Nations’ history. Two-thirds of all vetoes occurred during the Cold War, when East-West tensions hamstrung the Security Council. France and the United Kingdom, meanwhile, have not cast vetoes since 1989.

P5 members veto resolutions that they believe threaten their national interests, security, or foreign policy goals. The United States, for example, often uses its veto to defend its close partner Israel. Meanwhile, Russia has used its veto fourteen times in the past decade to prevent the United Nations from intervening in the Syrian civil war.Russia is protecting its close ally, the Syrian government in the wake of UN intervention in Libya. In that conflict, a limited mission to protect Libyan citizens escalated into a push to overthrow the country’s leader. This intervention left Russia indignant. Russia has even vetoed an investigation into the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

UN Security Council Reform

Political infighting among the P5 has frequently immobilized the Security Council. It has struggled to act even amid major world events, such as wars in Syria and Ukraine and the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. Such disagreements have led to calls for reform. Many UN member countries want to abolish the veto and redesign the Security Council.

Countries have also called for expanding the number of permanent Security Council members. They argue that the P5 under-represents several regions, including Africa and Latin America. Reform advocates also suggest that Germany (or the European Union), India, and Japan should have permanent-member status. Such a makeup would better reflect today’s global balance of power. Additionally, a 2010 Council on Foreign Relations report [PDF] notes that “the lack of perspectives from the global South [on the Security Council] reinforces perceptions that the UNSC is a neocolonial club, determining questions of war and peace for the poor without their input.”

However, chances of overhauling the Security Council are slim. The P5—as well as two-thirds of the United Nations’ entire membership—would have to agree to changes. Moreover, permanent members are unlikely to agree to have their power diminished.

With U.S.-China relations rapidly deteriorating and Russia’s relations with the United States, France, and the United Kingdom also highly contentious, the Security Council will likely continue to struggle to address today’s most pressing and politically polarizing issues.