What Is Peacekeeping?

In this free resource on the successes and failures of peacekeeping, learn about the UN missions tasked with transitioning countries out of war.

The world lacks a global police force capable of stopping violence in its tracks. However, it does have UN peacekeepers, who can help wind down conflicts and prevent them from recurring.

Take the case of El Salvador. Amid endemic inequality, repression, and political violence, the country descended into civil war in 1980. The conflict consumed the Central American nation for more than a decade. During the civil war, at least seventy-five thousand people were killed; a million more were displaced.

Despite the United Nations’ commitment to global peace and security, it refrained from direct intervention. This was due to the organization’s abiding respect for sovereignty—the principle that countries get to control what happens within their borders. As a result, the United Nations did not involve itself in El Salvador’s internal affairs.

The United Nations only interceded in 1991, after the Salvadoran government and the opposing insurgent group appealed for outside support to end the fighting. With both parties’ consent, the United Nations deployed a multinational force that helped monitor a cease-fire. Additionally, this force investigated war crimes and oversaw reforms of the country’s governing institutions. The United Nations later celebrated its peacekeeping mission. El Salvador transformed “from a country riven by conflict into a democratic and peaceful nation.”

Peacekeeping is not the same as peacemaking—much less warfighting. As the El Salvador mission illustrates, the United Nations struggles to prevent violence when wars are raging. However, the organization can help countries transition out of conflict when there is a peace to keep.

In this resource, we’ll explore peacekeeping operations, examining both their effectiveness and significant limitations.

Peacekeeping definition

Wars can technically end when fighting stops, but that doesn’t necessarily mean countries have achieved either peace or stability. In the aftermath of conflict, countries often experience economic dysfunction and mass displacement. Moreover, a deep sense of mistrust among former combatants is likely to exist. As a result, peace can easily backslide into violence, a phenomenon known as recidivism. Indeed, 60 percent [PDF] of intrastate conflicts in the early 2000s relapsed within five years.

UN peacekeepers can help countries avoid recidivism by promoting the rule of law, monitoring elections, and reintegrating fighters into society, among other functions. They accomplish those goals not just with a military or police presence but also by providing advisors, including economists, humanitarian workers, governance specialists, and legal experts.

For the United Nations to deploy a peacekeeping operation, it must clear two hurdles: First, it must have the warring parties’ consent.This condition is often difficult to achieve when governments do not want others interfering in their internal affairs. (However, sometimes both sides of a conflict embrace UN support as a way of advancing their legitimacy. Parties will also embrace UN involvement to secure a prominent seat at the negotiating table.) Second, the operation must be approved by the UN Security Council (UNSC). Overcoming this hurdle requires passing a vote by the fifteen-member body without a single veto from one of its five permanent members (the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom).

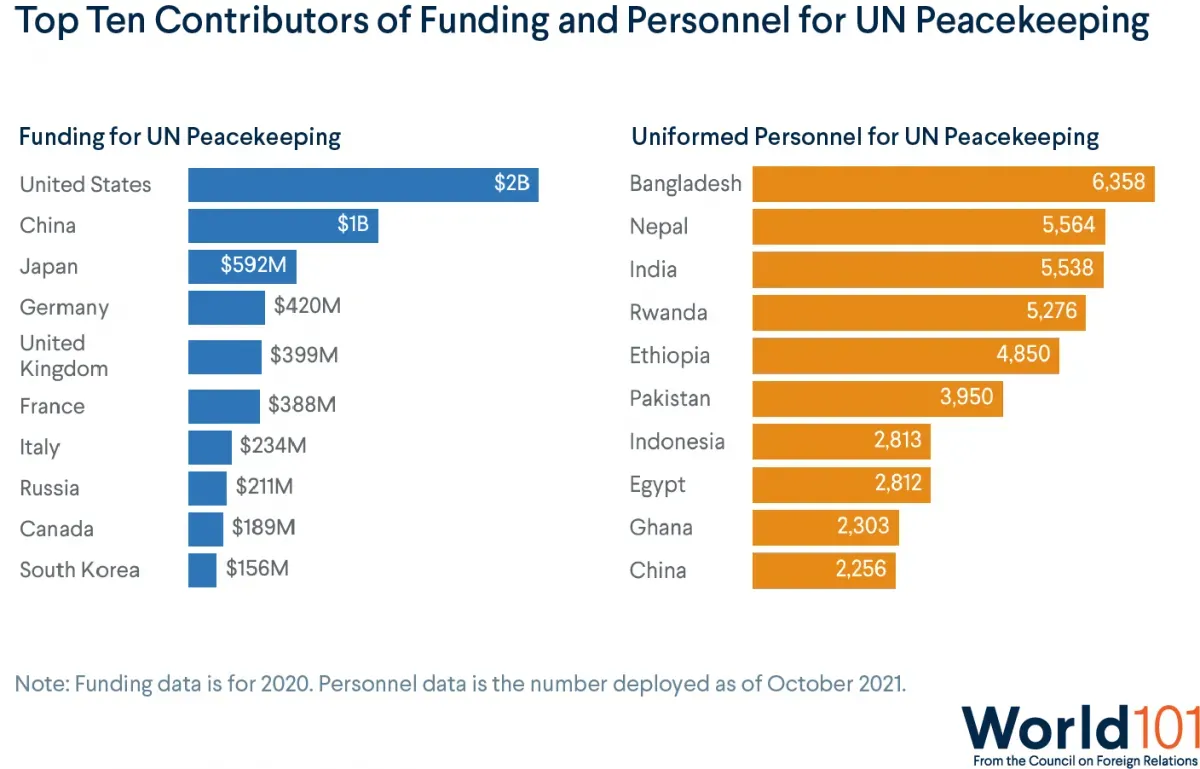

If an operation is approved, the UN General Assembly splits up the financing and equipping costs among UN member states assessed according to UN rules. As of 2021, the United States, China, and Japan contributed the most toward funding peacekeeping missions. Meanwhile, Bangladesh, Nepal, and India provided (at each country’s discretion) the greatest number of military and police forces [PDF] for UN missions.

UN peacekeeping missions

Since the organization’s founding in 1945, the United Nations has deployed more than one million peacekeepers from over 120 countries on more than 70 missions worldwide.

Guiding each mission is a specific mandate set by the UN Security Council. The directives range from limited ones, such as ceasefire monitoring, to broad and ambitious undertakings, like overhauling a national government. The mandate also dictates a mission’s size, which varies from a few hundred specialists to tens of thousands of peacekeeping troops.

The UN operation in El Salvador—which consisted of military, police, and civilian officers from seventeen countries—combined many different elements of peacekeeping. The operation supervised peace agreements between the Salvadoran government and a leftist insurgent group. Peacekeepers also oversaw amnesty guarantees and disarmament programs, like clearing over four hundred minefields throughout the country. Additionally, the mission supervised major overhauls to El Salvador’s electoral, judicial, military, and police institutions. Those efforts included training judges and court officials and developing curricula for military academies that emphasized human rights. Finally, peacekeepers established a commission to document the war’s atrocities. This documentation came in the hopes that an honest accounting would help facilitate reconciliation. The operation officially ended in 1995 and is generally regarded as a qualified success. Despite the end of the political conflict and the establishment of democratic processes, El Salvador today remains one of the world’s most violent countries.

As of December 2021, the United Nations operates twelve peacekeeping missions around the world. Six of those missions are located in Africa, where more than fifty thousand troops facilitate UN operations. Tens of thousands more operate peacekeeping or security missions under the auspices of the African Union, European Union, and other regional blocs.

What are the challenges for peacekeeping?

When the proper conditions exist, peacekeeping operations can lessen the severity of fighting and help countries emerge from conflict. Some experts suggest UN operations lead to shorter wars and fewer civilian deaths.

But, peacekeeping operations face numerous hurdles and limitations that undermine their effectiveness:

Consent requirement: The United Nations can only authorize peacekeeping operations with permission from the warring parties. In the absence of such consent—especially common when governments are the ones perpetrating the violence—civilians suffer while the United Nations is sidelined. The Syrian government, for instance, has expressed no interest in allowing the United Nations to intervene in the country’s ongoing, decade-long civil war.

Consent can also be withdrawn. When Egypt began preparing to go to war with Israel in 1967, the Egyptian government demanded that UN peacekeepers leave the country. Although war was clearly imminent, the peacekeepers had no option but to comply. If the UN had remained in Egypt without the government’s consent, they would be violating Egyptian sovereignty. As feared, war erupted between Egypt and Israel less than one month later.

Failure to protect civilians: Commitments to non-aggression and an inability to react to changing circumstances that fall outside their mandate can also hinder peacekeeping operations. In 2014, UN investigators found [PDF] that peacekeepers only responded to one in five cases in which civilians were threatened. Perhaps most infamously, UN peacekeepers monitoring local elections in Rwanda in 1994 were repeatedly ordered not to intervene as simmering ethnic tensions erupted into genocide. Peacekeepers were urged to stand down so as not to interfere in a domestic conflict and overstep the narrow scope of their mission. However, as UN peacekeepers stood on the sidelines, more than eight hundred thousand Rwandans were killed in just three months.

Such failures led to UN members endorsing in 2005 what became known as the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine. This principle states that countries have a fundamental sovereign responsibility to protect their citizens from genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and ethnic cleansing. If they fail to do so, that responsibility falls to the United Nations system, particularly the UN Security Council, which may take steps to protect those vulnerable people. Under such conditions, the United Nations can violate the sovereignty of the relevant country if needed. In other words, countries acting under UN auspices can use all means necessary—including military intervention—to prevent large-scale loss of life or displacement. The R2P doctrine was put to the test in 2011 amid Libya’s civil war. But the destabilizing effects of that humanitarian intervention and its evolution into a regime-change operation have made countries that were already wary of R2P, such as China and Russia, unlikely to green-light future humanitarian interventions.

To learn more about R2P, check out The Rise and Fall of the Responsibility to Protect.

Record of misconduct: Peacekeepers have repeatedly been accused of human rights violations, including sexual abuse. In the early 2000s, reports of UN personnel committing sexual violence plagued the United Nations’ efforts to conduct political stabilization, disarmament, and police reform in Haiti. In 2021, the United Nations withdrew 450 peacekeepers from the Central African Republic, following similar sexual abuse allegations. Although the United Nations has increasingly investigated such reports, none has led to a public conviction. (UN peacekeepers are heavily shielded from prosecution in the countries where they serve). UN peacekeepers have also been accused of corrupt practices—such as bribery and extortion—and gross misconduct. For example, peacekeepers were likely the source of a deadly cholera outbreak in 2010 that killed thousands of Haitians.

Budget constraints: In 2019, more than one hundred thousand peacekeepers were active in fourteen countries, constituting the second-largest military force deployed abroad, trailing only that of the United States. However, UN peacekeeping operates on a limited budget, accounting for less than 0.5 percent of global military expenditures in the 2021 fiscal year. With ambitious mandates and severe financial constraints, peacekeeping missions often struggle to fulfill their goals. For example, fewer than eighteen thousand UN personnel are tasked with protecting civilians in the Democratic Republic of Congo—a sprawling, mountainous country of ninety million people.

Peacekeeping: an imperfect tool

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan once said that UN peacekeeping is “the only fire brigade in the world that has to wait for the fire to break out before it can acquire a fire engine.” Indeed, the United Nations has no standing peacekeeping force; every operation must be established on an ad hoc basis. This reality compounds peacekeeping’s already significant challenges. As a result, peacekeeping is a largely ineffective foreign policy tool for stopping violence when war is raging.

However, proponents maintain that when the conditions for peace exist, peacekeeping can help shorten wars, protect civilians, and keep temperatures cool in the aftermath of conflicts.

Now that this resource has covered the fundamentals of peacekeeping, put these principles into practice with CFR Education’s companion mini simulation on Peacekeeping.