The Rise and Fall of the Responsibility to Protect

Sovereignty is sacred. But when lives are in danger, does that principle still apply?

An Indonesian peacekeeper waves a UN flag on the border between Lebanon and Israel in the southern Lebanese village of Adaisseh on November 30, 2009.

Source: Ali Dia/AFP via Getty Images

Teaching Resources—Building Blocks: Challenges (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

At the end of World War II, the world was desperate to avoid such horrific conflict in the future. After an unsuccessful attempt to drive multilateral cooperation through the League of Nations after World War I, national leaders came together to create the United Nations (UN). Designed as a forum for international engagement, the UN was founded to defuse international conflicts and to stop aggression from escalating into a full scale war. Underpinning this new world order was a respect for sovereignty—the principle that no country can interfere in the domestic affairs of another.

To preserve peace and defend human rights, the United Nations created multinational peacekeeping forces, ideally to work in coordination with local governments. Ideally, such forces were to work in coordination with local governments. But problems quickly emerged: how would these peacekeepers respond if a local government was the one committing violence against its own people? Could preventing a mass atrocity justify violating a country's sovereignty?

For decades, the United Nations maintained that sovereignty must be respected. But after the Rwandan genocide and wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, scholars and diplomats reevaluated this thinking. In 2005, UN members endorsed the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine. This idea asserts countries have a fundamental sovereign responsibility to protect their citizens. If they fail to do so, the UN has the responsibility to protect vulnerable people. R2P gives the UN (and its member countries) the right to violate another country's sovereignty if needed to protect innocent and engaged people. In other words, countries acting within the UN system can use all means necessary—including military intervention—to prevent large-scale loss of life.

The R2P doctrine was tested in 2011 amid Libya’s civil war. The UN's initial humanitarian intervention quickly evolved into a regime-change operation. This development led to divisive debates among world leaders over the delicate balancing act between respecting sovereignty and protecting human rights. This timeline traces the evolution of humanitarian intervention and R2P. It also looks to the doctrine's uncertain future after its controversial implementation in Libya.

After World War II—the deadliest conflict in human history, during which six million Jews were killed in an act of genocide—world leaders created the United Nations to prevent any similar fighting from occurring. As envisioned by its founders, the United Nations would mobilize a multinational force to assist countries in defending against external hostility and internal violence. But what would happen if those governments rejected UN intervention? The United Nations had no answer to this dilemma. Though a conflict might be unavoidable, the United Nations pledged first and foremost to respect the sovereignty of its member countries.

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum

United Nations

In the final days of World War II, representatives from forty-nine countries met in San Francisco. There they drafted the Charter of the United Nations, the founding document for a new international organization dedicated to world peace. The charter defined the United Nations’ mission: to protect countries’ sovereignty. Representatives also laid out the organization’s powers, including the ability to create a multinational military force armed to maintain peace and deter interstate aggression. These forces became known as UN peacekeeping units, who worked to enforce cease-fires, monitor elections, and protect the sovereignty of vulnerable countries with the express permission of local governments.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

The United Nations created new laws that protected human rights globally. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognized that all people are entitled to equal, inalienable rights—namely life, liberty, and security. Meanwhile, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide criminalized the deliberately harming a specific group of people for the first time under international law. Never before had the world come together to declare that all people were entitled to certain freedoms and rights. Moreover, the violation of these rights was now against international law. To this day, those documents serve as the standard by which governments are expected to treat their citizens.

United Nations

In July 1960, the United Nations deployed its largest peacekeeping operation yet—almost twenty thousand troops—to the Democratic Republic of Congo. The purpose of this operation as to assist the newly established Congo in expelling illegally stationed Belgium troops that refused to acknowledge its independence. Over the following four years UN peacekeepers worked with the local government to prevent civil war. When the peacekeepers left Congo in 1964, the United Nations had successfully facilitated an end to the violence in partnership with the Congolese government. Despite this success, the Soviet Union criticized the United Nations’ involvement in Congo and feared it would set a precedent for interfering in countries’ domestic affairs.

United Nations

UN peacekeepers can only operate with the permission of local governments. In Egypt, for example, the government allowed UN peacekeepers to patrol its tense border with Israel for over a decade. However, when Egypt began preparing for war with Israel in 1967 the Egyptian government demanded the UN peacekeepers withdraw. Although war was clearly imminent, the peacekeepers were forced to comply to avoid any violation of Egyptian sovereignty. One month later, the UN stood powerless as war erupted between Egypt and Israel.

Since 1945, the United Nations has worked to defend and respect the sovereignty of its member countries. But in the 1990s, a wave of mass atrocities shocked the global conscience. The UN repeatedly failed or refused to intervene in widespread human rights abuses and the massive loss of life in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. Recognizing that granting countries absolute sovereignty within their borders could lead to atrocities such as genocide and ethnic cleansing, experts strove to balance national sovereignty and the need to protect human rights.

Kevin Weaver/Getty Images

Kevin Weaver/Getty Images

Scott Peterson via Getty Images

In 1991, a military coup left Somalia without a functioning government. In response, the United Nations deployed peacekeepers to monitor a tenuous cease-fire among warring factions and to deliver aid to a starving population. Despite their humanitarian mandate, UN peacekeepers often became the target of attacks from local militias. To curb this violence, the United Nations authorized the United States to capture militia leaders in the Somali capital in 1993. The operation—later popularized by the book and movie Black Hawk Down—was met with fierce resistance, resulting in the deaths of eighteen American soldiers, one Malaysian soldier, and hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Somalis. As televisions across the world showed images of fallen servicemen being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu, countries became increasingly wary of committing their troops to future peacekeeping missions.

Scott Peterson via Getty Images

In January 1994, UN peacekeepers were monitoring local elections in Rwanda. But when simmering ethnic tensions erupted into genocide later that year, those same peacekeepers were repeatedly ordered not to intervene. Following conflict in Somalia, the UN was wary of intervening a domestic conflict and overstepping the narrow scope of their mission. However, as UN peacekeepers stood on the sidelines, more than eight hundred thousand Rwandans were killed in just three months. This staggering death toll prompted an extensive UN investigation, which concluded that member countries had ordered their peacekeepers to stand down. The UN decided to prioritize their own safety after incurring mass casualties previous missions.

Reuters

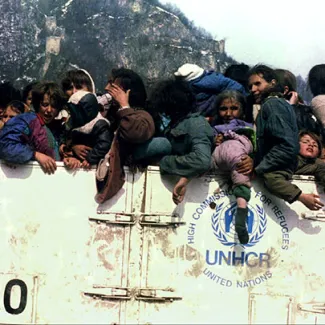

In 1995, just one year after eight hundred thousand people died in Rwanda, peacekeepers faced another violent civil conflict. Following the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, a civil war in the Balkans pitted Bosnian Muslims against Bosnian Serbs. UN peacekeepers were protecting the Muslim town of Srebrenica, but when the Bosnian Serb army began advancing in their direction, UN peacekeepers were ordered not to fire. The peacekeepers were inadequately armed, and UN leaders feared that conflict could endanger ongoing peace negotiations with the Serbian authorities. After the UN peacekeepers stood down, the Bosnian Serb army methodically executed some eight thousand Bosnian Muslim men and boys. An international tribunal later designated the massacre a genocide.

Oleg Popov/Reuters

In 1999, violence surged yet again in the former Yugoslavia, as Serbian authorities persecuted Kosovar Albanians (ethnic Albanians living in Kosovo, a region within Serbia) who called for an independent country. Despite the immediate threat of ethnic cleansing, the United Nations could not agree whether to intervene. This time, however, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) refused to tolerate mass violence on the European continent. Led by the United States, the alliance launched an extensive bombing campaign in an effort to end the conflict. NATO concluded that attacking Serbia was justified in order to end ethnic cleansing and prevent mass atrocities. This decision remains controversial. On the one hand, it pushed the Serbians to negotiate an end to hostilities. But the campaign also lacked UN authorization, violated Serbian sovereignty, and caused widespread damage and displacement. The bombing campaign contributed to thousands of deaths and displaced over a million Kosovar Albanians. NATO's actions demonstrated that there was interest among some world leaders in undertaking humanitarian interventions. However, it was made clear that guidelines for such interventions were necessary.

Ray Stubblebine/Reuters

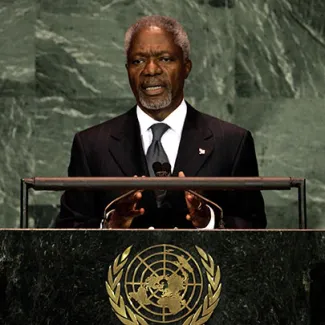

After the violence in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, the United Nations sought to ensure such tragedies never again occurred. World leaders were compelled to revisit the question of whether a country’s sovereignty could be justifiably violated in order to stop a mass atrocity. In 2005, UN members endorsed the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine. This doctrine states that countries have a fundamental responsibility to protect their citizens. If countries failed to do so, then the rest of the world would be forced to intervene. In other words, countries can use all means necessary—including military intervention—to prevent large-scale loss of life. The R2P doctrine represented a radical shift from previous decades. Prior to 2005, unilateral humanitarian intervention was considered an unlawful violation of a country’s sovereignty. Applying this doctrine, however, would prove tricky.

The United Nations invoked the R2P doctrine in 2011 after Muammar al-Qaddafi, Libya’s longtime dictator, responded to local protests with extreme violence. Fearing a massacre, the United Nations authorized NATO to breach Libya’s sovereignty in order to protect civilians from Qaddafi’s forces. The mission was intended to be narrow in scope, but it quickly evolved into a destabilizing regime-change operation. In the end, the Qaddafi regime was toppled, but civil war still rages in Libya. Today, the country is arguably more unstable and violent than ever. As a result, countries that were already wary of R2P, such as China and Russia, are unlikely to green-light future humanitarian interventions.

Jessica Rinaldi/Reuters

Jessica Rinaldi/Reuters

Suhaib Salem/Reuters

Sparked by protests throughout the Arab world that became known as the Arab Spring, the Libyan revolution started in the city of Benghazi on February 17, 2011. Hundreds of protesters organized a “Day of Rage,” demanding the fall of the country’s longtime dictator, Muammar al-Qaddafi. As protests spread across the country, Qaddafi’s security forces responded with violence, leaving hundreds dead. In the following weeks, fighting escalated as Qaddafi’s government began launching air strikes on opposition cities. During a televised speech, Qaddafi called rebels “cockroaches” and vowed to cleanse Libya “house by house.” Those threats sparked concerns of an impending humanitarian catastrophe and prompted Arab leaders to call for military intervention in Libya.

Monika Graff/Getty Images

Amid the growing crisis in Libya, the UN Security Council—the United Nations’ most powerful decision-making body—debated whether to invoke the R2P doctrine. Authorizing such an operation requires majority approval from the Security Council; however, any one of five permanent Council members—the United States, China, France, Russia, or the United Kingdom—can single-handedly veto a resolution. On this occasion, China and Russia abstained, allowing the vote to pass. Resolution 1973 granted NATO permission to implement a no-fly zone over Libya to protect the country’s civilians from Qaddafi’s air force. The United Nations had invoked the R2P doctrine, authorizing the deliberate violation of a country’s sovereignty on humanitarian grounds.

Paul Hanna/Reuters

The United Nations authorized NATO to conduct a limited humanitarian intervention in Libya in order to protect the country’s civilians. But on March 25, 2011, President Barack Obama stated that Libya would not be safe until Qaddafi’s forces stopped attacking protesters. He promised that the NATO mission would continue until Qaddafi stepped down. This speech signaled a fundamental shift in NATO’s mission: rather than simply grounding Qaddafi’s air force through a no-fly zone, NATO would now undertake a broader political mission of regime change in Libya. This shift infuriated China and Russia, which accused NATO of overstepping its UN mandate. In the following months, rebels took over most of Libya with extensive NATO military support.

Goran Tomasevic/Reuters

Rebel forces captured, tortured, and executed Qaddafi in his hometown of Sirte on October 20, 2011. NATO leaders hoped Qaddafi’s ouster would end violence in Libya, but the country soon spiraled into even greater chaos. Rebel forces splintered into competing militias, which continue to fight a civil war that has killed thousands and displaced many more. Today, Libya is a failed state, a haven for extremist groups like the self-proclaimed Islamic State and al-Qaeda. Libya is also the site of an international proxy conflict that further destabilizes the nation. Recognizing NATO's role in unleashing this instability, President Obama called his administration's failure in Libya the worst mistake of his presidency.

Paulo Filgueiras/United Nations

China and Russia vowed to never again allow the United Nations to violate the sovereignty of a member country after humanitarian intervention in Libya evolved into a regime-change operation. On January 31, 2012, as nearby Syria descended into civil war and Arab leaders requested UN intervention to prevent mass civilian casualties, China and Russia vetoed the usage of R2P. To this day, China and Russia have used their veto power on the UN Security Council to block more than fifteen attempts by the United Nations to intervene in Syria.

In Syria, over four hundred thousand people have been killed with millions more displaced since the start of the country’s civil war. In Yemen, a civil war has produced the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. And in Myanmar, human rights advocates accuse the government of committing genocide against the Rohingya minority. But in each of these crises, the United Nations’ response has been limited. Despite the imminent threat to several civilian populations across the world, the UN is once again divided on the appropriate balance between respecting sovereignty and protecting human rights. For a brief moment, countries agreed that preventing a mass atrocity justified violating a country’s sovereignty. But the 2011 Libya intervention shattered international consensus on the R2P doctrine. Since that destabilizing intervention, China and Russia in particular have used their veto power on the UN Security Council to block other such interventions. As a result, the United Nations has been unable to use military action to mitigate some of the world’s most violent conflicts.

Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters

Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters