The Rise and Fall of the Responsibility to Protect

Sovereignty is sacred. But when lives are in danger, does that principle still apply?

At the end of World War II, the world was desperate to avoid such horrific conflict in the future. After an unsuccessful attempt to drive multilateral cooperation through the League of Nations after World War I, national leaders came together to create the United Nations (UN). Designed as a forum for international engagement, the UN was founded to defuse international conflicts and to stop aggression from escalating into a full scale war. Underpinning this new world order was a respect for sovereignty—the principle that no country can interfere in the domestic affairs of another.

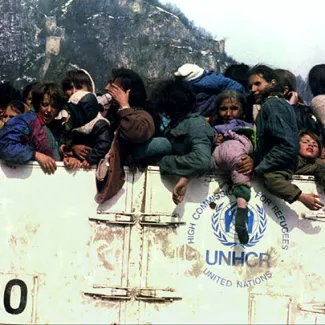

To preserve peace and defend human rights, the United Nations created multinational peacekeeping forces, ideally to work in coordination with local governments. Ideally, such forces were to work in coordination with local governments. But problems quickly emerged: how would these peacekeepers respond if a local government was the one committing violence against its own people? Could preventing a mass atrocity justify violating a country's sovereignty?

For decades, the United Nations maintained that sovereignty must be respected. But after the Rwandan genocide and wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, scholars and diplomats reevaluated this thinking. In 2005, UN members endorsed the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine. This idea asserts countries have a fundamental sovereign responsibility to protect their citizens. If they fail to do so, the UN has the responsibility to protect vulnerable people. R2P gives the UN (and its member countries) the right to violate another country's sovereignty if needed to protect innocent and engaged people. In other words, countries acting within the UN system can use all means necessary—including military intervention—to prevent large-scale loss of life.

The R2P doctrine was tested in 2011 amid Libya’s civil war. The UN's initial humanitarian intervention quickly evolved into a regime-change operation. This development led to divisive debates among world leaders over the delicate balancing act between respecting sovereignty and protecting human rights. This timeline traces the evolution of humanitarian intervention and R2P. It also looks to the doctrine's uncertain future after its controversial implementation in Libya.

United Nations Creates New World Order

Birth of United Nations Gives Rise to New Peacekeeping Forces

United Nations Creates Human Rights Canon

UN Peacekeepers Help Bring Stability to Congo

Peacekeepers Unable to Keep Peace in Egypt

Responsibility to Protect Doctrine Emerges After Tumultuous Decade

Peacekeepers Come Under Fire in Somalia

Peacekeepers Fail to Intervene in Rwandan Genocide

Massacre in Srebrenica Unfolds Before UN Peacekeepers

NATO Undertakes Armed Intervention in Kosovo

United Nations Embraces Responsibility to Protect

Responsibility to Protect Invoked in Libya With Destabilizing Consequences

Libyan Revolution Begins in Benghazi

United Nations Invokes Responsibility to Protect in Libya

NATO’s Goals in Libya Shift to Regime Change

Qaddafi Killed, But Libya Descends Into Chaos

After Libya Crisis, UN Security Council Refuses to Act in Syria

R2P Sidelined as World Splits on Balance Between Sovereignty and Human Rights