People and Society: Middle East and North Africa

The Middle East is the birthplace of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism and is a region of immense diversity.

The Middle East is the birthplace of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism and is a region of immense diversity. While Arabs compose the majority of the Middle East’s population, the region is also home to Berbers, Kurds, Jews, Persians, Turks, and a vast array of other ethnic and religious minorities. But such diversity does not necessarily translate into equality, as minorities often face legal discrimination within their own countries. Women, too, fight for equal rights in a region with some of the lowest rates of female political participation in the world. Despite the region’s many challenges, political leaders often capitalize on society’s divisions to advance various, competing agendas throughout the Middle East.

Religion Runs Deep in Middle East

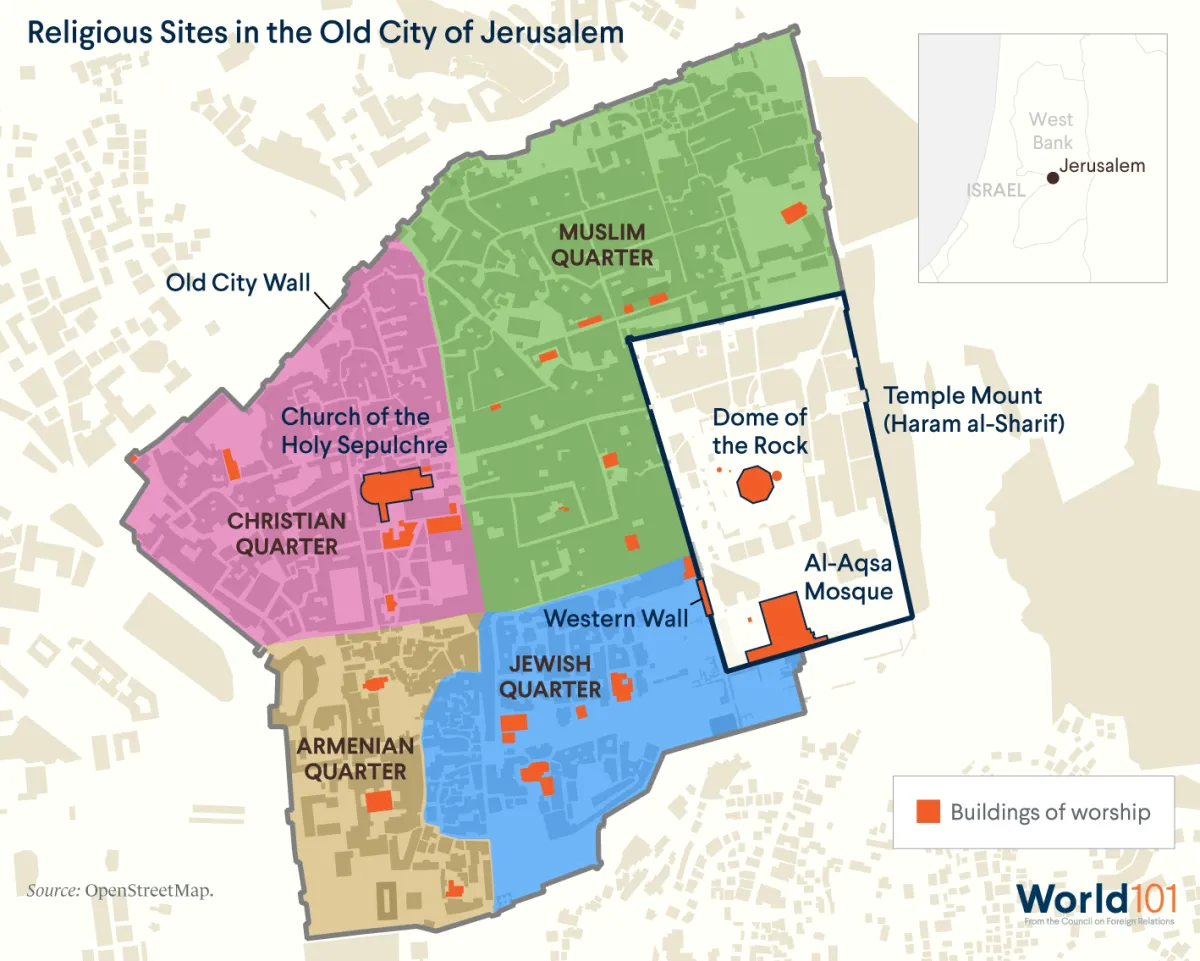

For many residents of the Middle East, religion is a source of great strength and social cohesion. The region is the birthplace of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, all of which trace their roots back to the same founding patriarch, Abraham. Today, there are around 2.3 billion Christians, 1.8 billion Muslims, and 14 million Jews around the world, and every year pilgrims visit the Middle East’s holy places, including the Church of the Nativity (believed to be Jesus’s birthplace) in Bethlehem and the Western Wall (a Jewish holy site) in Jerusalem. In 2018, over two million Muslims traveled to Saudi Arabia for Hajj, a pilgrimage to the city of Mecca that Muslims are required to make at least once in their lives. But, as in other parts of the world, religion can fuel competition and unrest. The Old City of Jerusalem is even divided along religious lines, and Palestinians and Israeli police have repeatedly clashed at one of its most-venerated (and contested) holy sites—known as the Temple Mount to Jews and the Haram al-Sharif to Muslims.

Politicians Exploit Sunni-Shia Divide to Advance Agendas

In the seventh century, Muslims were divided over who should become Islam’s next political and religious leader after the Prophet Mohammed’s death. They split into two groups—Sunnis and Shias—and although they shared basic principles like a belief in the Quran (Islam’s holy book), they built unique identities around their specific religious practices that diverged over the following centuries. Today, roughly 85 percent of the world’s nearly two billion Muslims are Sunni and about 10 percent are Shiite, with Muslims from smaller sects making up the remaining percentage. While Sunnis and Shias have lived peacefully side by side for much of Islamic history, the past century has seen a rise in religious conflict that has killed thousands in places like Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Political leaders have often exploited such divisions to advance political agendas in the region. Saudi Arabia—one of the most powerful Sunni-majority countries—backs Sunni governments and armed groups in places like Bahrain and Yemen while Saudi Arabia’s rival, Iran—the Middle East’s largest Shia-majority country—has supported Shiite groups like the Lebanese organization Hezbollah as well as Shiite militias in Iraq and Syria.

Kurds Face Historical Oppression Across Region

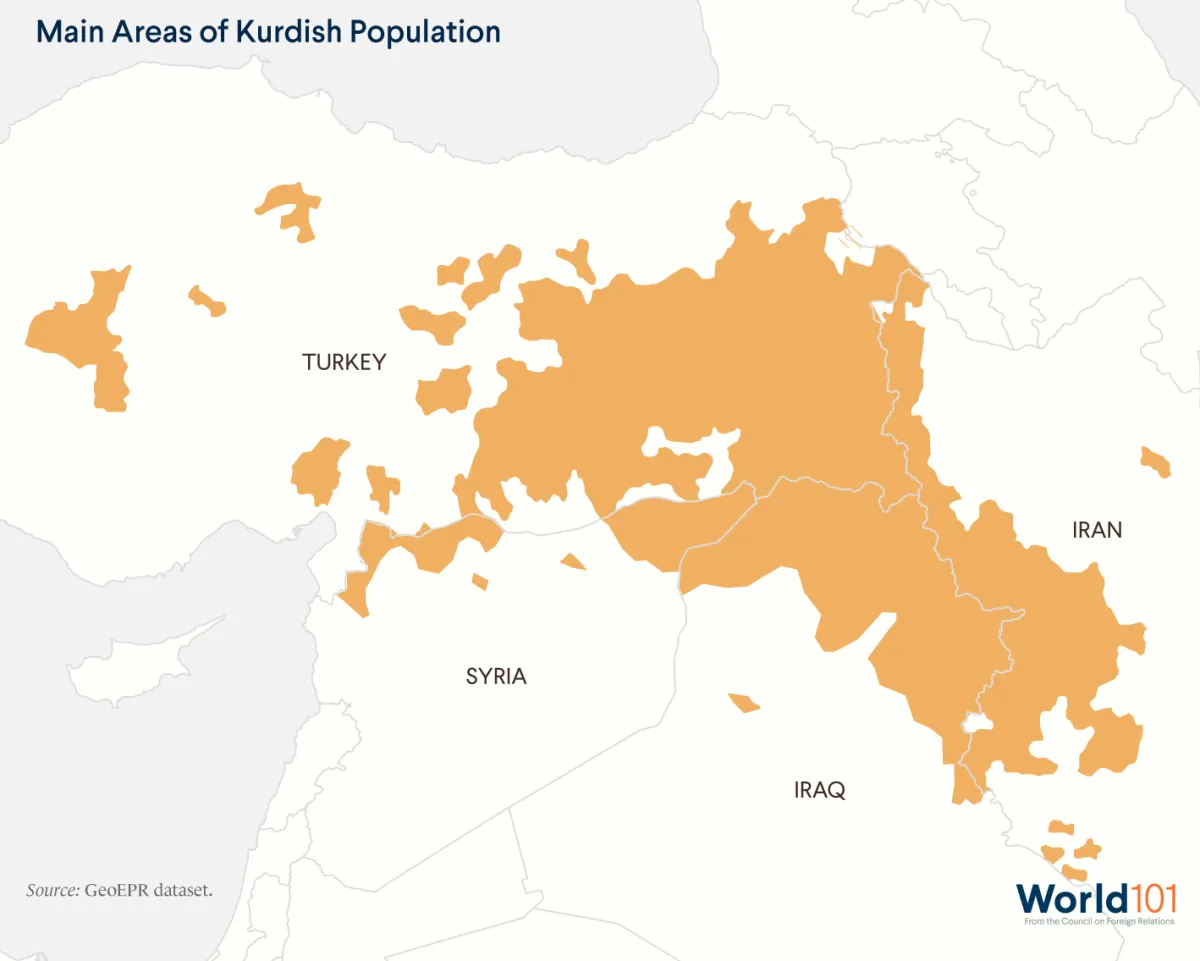

Approximately thirty million Kurds live in Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, forming one of the world’s largest ethnic groups without a country. Since the end of World War I, when the Kurds were denied independence following the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, they have been refused basic rights and freedoms such as the right to start Kurdish-language schools and newspapers. They have also been the target of state-sponsored violence. In Iraq in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein’s regime repeatedly used chemical weapons on Kurdish villages, infamously killing five thousand civilians in the town of Halabja in 1988. In Turkey, the government frequently conducts raids and mass arrests in Kurdish-majority areas, targeting the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (also known as the PKK), an insurgent group that has killed thousands of Turkish forces and civilians over more than thirty years in its quest for an independent Kurdistan. In Syria, approximately eleven thousand U.S.-backed Kurdish fighters have died battling the Islamic State. Moreover, the recent U.S. withdrawal from large parts of Syria has exposed these same Kurdish forces to violent clashes with the Turkish military.

Female Political Participation Among Lowest in World

The Middle East has the unflattering distinction of having some of the lowest female political participation rates in the world. With the exception of Israel, no country in the region has ever had a female head of state.And in 2019, only 17 percent of lawmakers in the Middle East were women, behind every other region. (The United States is not much higher at only 23 percent.) Women make up less than 1 percent of Yemeni lawmakers, and in Saudi Arabia women only received the right to vote and run for municipal office in 2015. In countries like Iraq, Jordan, and Morocco, a certain percentage of parliamentary seats (known as quotas) is reserved for women, yet female politicians are often still excluded from important economic and national security policymaking. Frustrated at their lack of a political voice, women across the Arab world played a prominent role in the 2011 Arab Spring protests. However, this participation rarely translated into political inclusion.

Lack of Gender Parity Extends to Legal Discrimination

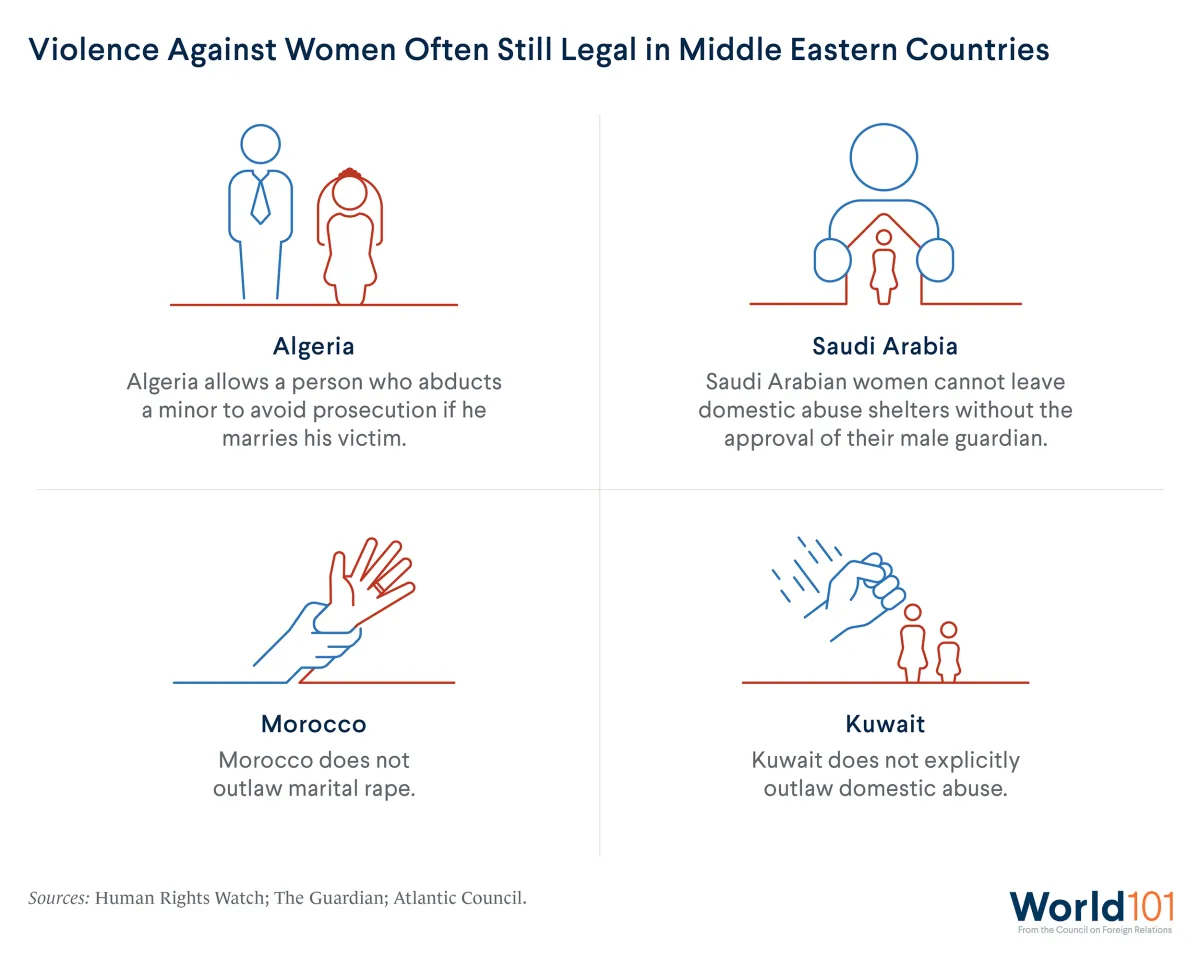

Laws in the Middle East are often discriminatory against women. Unlike most countries around the world, where children automatically acquire their parents’ citizenship, twelve countries in the Middle East restrict a woman’s right to confer nationality. That means, for example, that a person with a Kuwaiti mother and foreign father would not automatically become a Kuwaiti citizen. Discrimination also extends to inheritance rights where many women in Arab countries receive half as much as their male relatives. And in Saudi Arabia, the government requires women to obtain a male guardian’s permission to marry, receive certain healthcare, and be released from prison. In recent years, however, there have been some promising developments. Tunisia drafted a new constitution in 2014 that afforded women equal rights before the law. In 2018, Saudi Arabia granted women the right to drive, and in 2019 the Saudi government relaxed—but did not eliminate—its guardianship laws, allowing women to get passports and travel abroad without approval from a male relative.

Enrollment Rates Rise, But Schools Underperform

School enrollment rates in the Middle East have soared over the past fifty years, surpassing global averages. Students are more than three times as likely to be in secondary school (high school) and more than seven times as likely to be in tertiary school (university, college, trade school) compared to 1970. However, the region struggles to translate high enrollment into high-quality education. Arab countries, for example, have consistently scored well below global averages on standardized tests for reading, science, and mathematics. Additionally, the emphasis on rote learning (repetition-based memorization), rather than critical thinking skills, at many of the region’s schools and universities leaves young adults ill equipped to join the professional workforce in a region with a 40 percent unemployment rate for university graduates. While the Middle East has a long history of higher education—including the world’s oldest university, which is in Morocco and dates back to 859—today, very few of the region’s universities rank among the world’s top higher education institutions.

Humanitarian Crises Prove Extremely Deadly

Over the past decade, wars in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen have resulted in tremendous loss of life. These conflicts are so deadly not only from the violence, but also because of the humanitarian crises that result when civilians lose access to food, medicine, and shelter. Yemen, for example, is experiencing the world’s “worst humanitarian crisis” as a result of the ongoing civil war between Iranian-backed Houthi rebels and the Saudi-backed Yemeni government. More than one hundred thousand people have died from violence, while eighty-five thousand children under the age of five are believed to have died from starvation between 2015 and 2018. Ten million Yemenis (more than a third of the country’s population) are at risk of food shortages, hunger, and starvation amidst potentially the worst famine in a hundred years. These challenges are exacerbated by the Saudi-led coalition’s naval and air blockade, which prevents humanitarian aid from entering the country, and by Iranian-backed rebels who hoard the limited remaining resources in what is already the Middle East’s poorest country.

Region Home to Millions of Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons

Recent conflicts in the Middle East have caused millions to flee their homes. Over ten million people are internally displaced within their countries. More than seven million people have relocated around the world as refugees, the vast majority of whom have fled to neighboring countries, including Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Jordan, a country of 10 million people, hosts more than 750,000 refugees from Iraq, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. Jordanian authorities put that figure as high as 1.3 million. (Jordan is also home to 2.2 million Palestinian refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1967 Six Day War—the vast majority of whom are now citizens.) Over the past decade, Jordanian officials have struggled at times to provide public services with the influx of so many people. Some public schools have implemented a two-shift system—teaching different groups in the morning and afternoon—in order to accommodate Syrian refugees, and hospitals have had to raise fees for medical services due to growing numbers of patients and a lack of funds.

Palestinian Refugees Unable to Return to Former Homes

Palestinians are one of the world’s largest groups of refugees, and their continued displacement is a leading reason why Israeli-Palestinian peace remains so elusive. Around seven hundred thousand Palestinians became refugees mostly in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria by the end of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and another three hundred thousand Palestinians fled their homes during the 1967 Six Day War. Today, there are some five million Palestinian refugees around the world, including generations of descendants. The United Nations has an entire agency (UNRWA) exclusively dedicated to providing humanitarian aid and support for this large community. Palestinian leadership demands that refugees be allowed to return to their former homes in what is now Israel (commonly known as “the right of return”), arguing that any final Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement had to address this issue. While Israel allows any person (or spouse of a person) of Jewish ancestry to immigrate to Israel and acquire citizenship, Israel has consistently rejected extending such rights to displaced Palestinians, fearing that it would turn the Jewish state into a binational state.

Demographics Complicate Israeli-Palestinian Relations

Israel has occupied the Palestinian territories since the 1967 Six Day War. Since then, Israel has established Jewish housing complexes known as settlements in the West Bank and set up security checkpoints and border walls throughout these areas to control the population and reduce instances of terrorism. Despite controlling the Palestinian territories for over fifty years, Israel has never formally annexed most of this land. Why? Officially claiming Palestinian lands as part of Israel would require extending Israeli citizenship to millions of Arabs, which Israel opposes for demographic reasons. Israel was founded as a Jewish, democratic country, and Jews have historically composed around 80 percent of the population. But if Israel annexed Palestine (or if most countries concluded that Israel’s occupation effectively amounted to annexation), Jews would compose just over 50 percent of the population and could conceivably become a minority in the future. In such a scenario, Israel would be left to decide whether it wants to be a Jewish country (by denying Arabs citizenship) or a democratic country (by granting Arabs citizenship but losing its Jewish majority). Lately, right-wing parties in Israel have vowed to annex select parts of the West Bank, specifically the Jewish settlements and the geostrategically important Jordan Valley.

Health Outcomes Improve, but New Challenges Emerge

The Middle East has made dramatic improvements in its health outcomes over the last fifty years. Life expectancy has increased by over twenty-two years and is now higher than the global average. Maternal mortality rates have similarly improved, dropping to just one quarter of the global average. These health gains coincide with the Middle East’s economic development and an overall reduction in the region’s poverty rates. However, the region faces new health challenges. The Middle East, for example, has the world’s highest rates of diabetes, with total incidences projected to double over the next twenty-five years. And obesity—particularly among women—is yet another concern, with rates higher than 40 percent in countries like Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Oil Fuels Rise of Gulf’s Megacities

Throughout the early twentieth century, Dubai was a sleepy, pearl-diving town, home to only a few thousand residents. That changed in 1966 when oil was first discovered offshore. Revenue poured into Emirati coffers, transforming Dubai in just a few decades into today’s booming metropolis and global financial capital. Throughout the Gulf, countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have used their discoveries of oil to finance the development of skyscraper-lined megacities out of the literal desert. This explosion of wealth has also fueled something of a cultural arms race, with Gulf countries competing to build more and more expensive pillars of art, entertainment, and architecture. The United Arab Emirates recently opened a second branch of the Louvre in Abu Dhabi, Qatar is preparing to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup in air-conditioned stadiums, and Saudi Arabia has begun construction on what’s set to become the world’s first kilometer-high skyscraper.

Opportunities and Exploitation for Gulf’s Migrant Workers

Behind the creation of the Gulf’s megacities is a massive workforce of predominantly South Asian migrant workers who frequently face exploitative and unsafe working conditions. Millions of Bangladeshis, Filipinos, Indians, Nepalese, and Pakistanis work in the Gulf, where migrant workers comprise over 95 percent of the construction and domestic workforce. In several countries they form a majority of the total population. Qatari citizens, for example, compose just 12 percent of their country’s population. Migrant workers travel to the region in search of higher-paying jobs and sent over $100 billion from Gulf countries back to their families in 2017. But in what is known as the kafala (“sponsorship”) system, low-skilled migrant workers in the Gulf require local sponsors to oversee their visa and legal status. This often results in exploitation, where employers deprive vulnerable migrant workers of their passports, trapping them in dangerous and underpaid (or entirely unpaid) labor.

Climate Change Threatens Middle East

The Middle East is highly vulnerable to the global threat of climate change. In 2016, Kuwait and Iraq saw record-setting temperatures that reached 129 degrees (54 degrees Celsius), while a heat wave in the United Arab Emirates the following year resulted in cars catching fire. Soaring temperatures and increasingly dry environments have also exacerbated forest fires, notably in Lebanon, which in 2019 experienced its most destructive blazes in decades. And droughts have worsened in the world’s most water-scarce region, threatening the Middle East’s extremely limited arable land and forcing countries to rely more heavily on food imports to sustain their growing populations. Meanwhile, rising sea levels put coastal countries, including Egypt, Kuwait, Libya, Qatar, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates, at risk of floods. Such climate events have the potential to fuel mass displacement and increase competition over limited resources like water in an already tumultuous region.