Politics: East Asia & The Pacific

Some of the world’s most successful democracy stories come from East Asia and the Pacific.

Some of the world’s most successful democracy stories come from East Asia and the Pacific: South Korea and Taiwan transitioned from military dictatorships to vibrant democracies in the 1990s, and millions there participate in free and fair elections. However, elsewhere in the region, the opposite trend is taking place. Democracies in the Philippines and Thailand are backsliding, as their leaders impose restrictions on free press and punish political opponents. Meanwhile, one of the world’s most repressive governments is in North Korea, where 90 percent of television airtime is devoted to propaganda. China has expanded internet censorship and surveillance systems, eroded Hong Kong’s democracy, and forcibly detained over one million Muslims in so-called reeducation camps. Singapore has charted its own path, implementing a political system that combined authoritarian rule and economic modernization, inspiring similar models around the world.

Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan: Democratic Success Stories of Northeast Asia

Though Northeast Asia is home to authoritarian governments like North Korea’s and China’s, it also includes some of the most successful stories of democratization of the twentieth century. Japan transitioned from an imperial monarchy to a democracy after its defeat in World War II. South Korea had a rocky start following the Korean War, with several decades of military dictatorship before eventually turning to democracy in the 1980s. Taiwan went along a similar trajectory: its one-party dictatorship finally ended in the 1990s with the island’s first multiparty elections, beginning Taiwan’s transition toward becoming one of the world’s most vibrant democracies.

Southeast Asian Countries at Risk of Democratic Backsliding

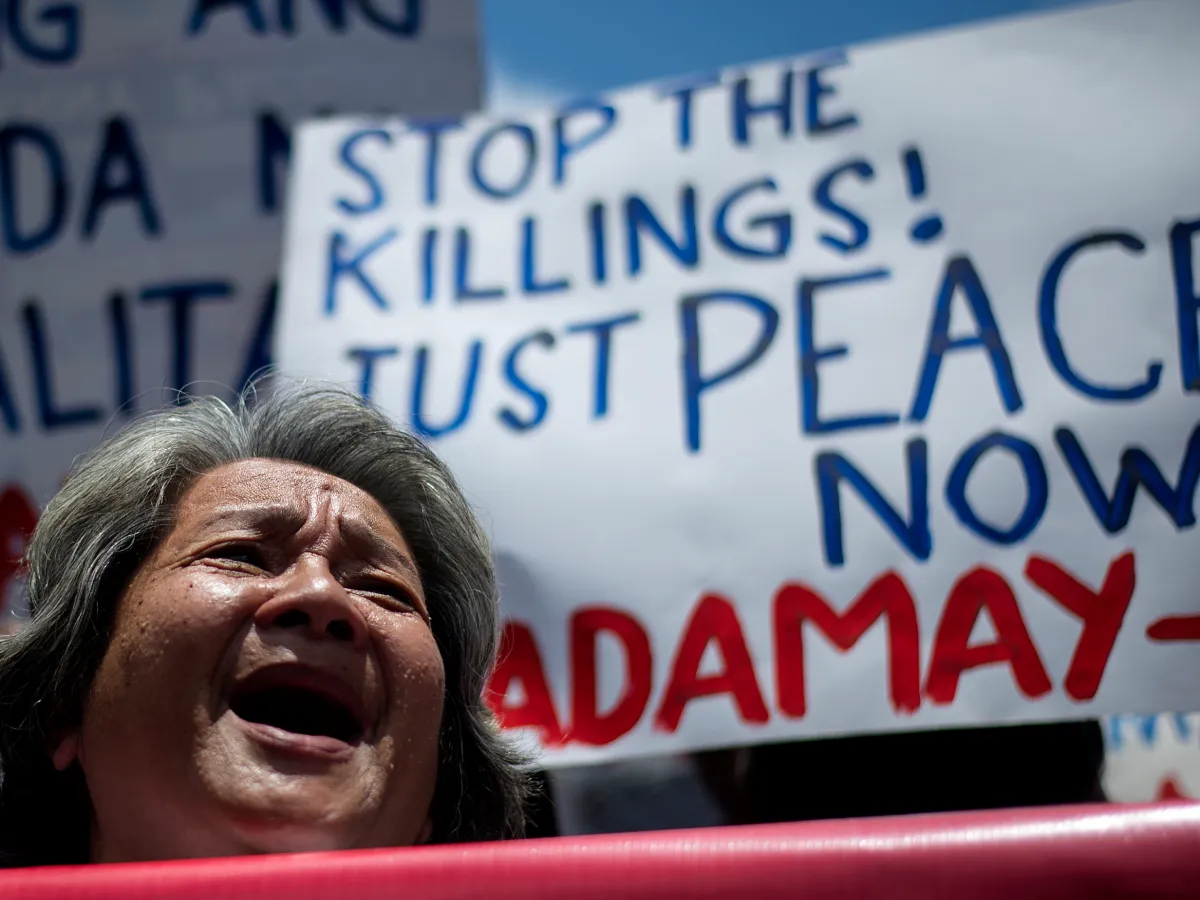

Southeast Asia is in the throes of rising populism and democratic backsliding, part of a troubling global trend. After a period of democratization in the 1990s and early 2000s, many Southeast Asian countries are now regressing into more authoritarian regimes. Cambodia’s government banned the main opposition party before the 2018 election, turning the country into a one-party state. In the Philippines, formerly one of Southeast Asia’s most dynamic democracies, President Rodrigo Duterte has eroded democratic foundations through extrajudicial killings, a crackdown on the press, and increased political meddling in the judiciary. And in Thailand, the military ousted a democratically elected government through a coup in 2014, the country’s twelfth since 1932.

Singapore Implements Model of Successful Economy, Limited Freedoms

While liberal democracies like the United States, Germany, and Japan have experienced enormous economic success, Singapore has achieved prosperity through a different style of government. It implemented a model that combined authoritarian governance and economic modernization, transforming the natural resources–lacking country into one of the world’s most competitive economies. After independence, in 1965, Singapore faced a lack of infrastructure, concerns of ethnic and racial tensions, and threats from its much larger neighbors. Nevertheless, Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew delivered a high quality of life for Singaporeans by growing the economy and maintaining political control. The government invested over 20 percent of the national budget into education, paid politicians high salaries to attract the best talent to government, and provided universal, low-cost public housing and health care. But at the same time, the government suppressed opposition parties, banned protests, and routinely censored the press. Many experts view China as following Singapore’s model of development.

Under Xi, China Opens Investments Abroad, Tightens Grip at Home

Few of today’s world leaders loom larger than China’s Xi Jinping. Since coming to power in 2012, he has dramatically changed his country through several signature policies. Under Xi, China has continued to expand economically, built military bases in the disputed South China Sea, embarked on an ambitious global project called the Belt and Road Initiative, and introduced a plan for China to become the leader in technologies like artificial intelligence. But at home, Xi has overseen an aggressive and controversial anticorruption campaign; increased internet censorship and domestic surveillance; planned a national system of “social credit,” which will reward and punish monitored citizen behavior; and persecuted minorities. Xi’s influence is not likely to wane any time soon. In March 2018, the Chinese government removed the constitutional limit on presidential terms, paving the way for Xi to remain in power indefinitely.

“One Country, Two Systems” Erodes Hong Kong’s Identity and Democracy

When Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997 after more than one hundred years of British rule, China implemented a “one country, two systems” policy. Hong Kong became part of China, and in return Beijing promised to allow Hong Kong to keep its democracy, freedom of speech and press, and distinct culture for at least another fifty years. But Hong Kongers have accused China of trying to erase their identity through a “mainlandization” campaign—promoting Mandarin Chinese over the native Cantonese dialect and building giant infrastructure projects linking Hong Kong and the mainland. More worrying, many Hong Kongers accuse China’s Communist Party of eroding Hong Kong’s democracy by ensuring that only pro-Beijing politicians can run for office. While China continues to tout “one country, two systems” as a viable model, including for eventual reunification with Taiwan, many Hong Kongers argue that the policy has already failed. Many observers view the case of Hong Kong as a litmus test for whether China will honor the international commitments it has made as its power increases.

Region Home to Ethnic Conflicts and Separatist Movements

Even though the region has seen rapid economic growth, many countries continue to face domestic conflicts, which usually have a religious or ethnic dimension. In southern Thailand, a Muslim separatist movement is seeking greater autonomy, claiming the government is imposing Thai-Buddhist culture on the predominantly Muslim region. Nearly seven thousand civilians have died in the conflict since 2001. In neighboring Laos, an insurgency led by some members of the Hmong ethnic minority has flared up intermittently since 1975. Meanwhile, the Indonesian government has killed hundreds of thousands of ethnic Papuans over the past fifty years in an ongoing struggle for Papuan independence. And in the Philippines, a bloody conflict over autonomy in majority-Muslim provinces has endured for decades. Although the government passed a law in 2018 granting these provinces control over their own resources and customary laws, there’s no guarantee the conflict will end.

Myanmar Military Commits Genocide Against Rohingya Minority

In 2017, the Myanmar government committed acts of genocide, according to the United Nations, against a Muslim ethnic minority known as the Rohingya, forcing more than seven hundred thousand people to flee the country. Myanmar’s military killed at least 6,700 Rohingya between late August and September 2017 alone, with the estimated death toll as high as 40,000 as of 2019. World leaders have sharply criticized Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Myanmar’s civilian leader, for ignoring the claims of genocide in her country and essentially condoning the military’s actions against the Rohingya. Since August 2017, almost the entirety of Myanmar’s Rohingya population has crossed the border into neighboring Bangladesh, where government officials are struggling to accommodate them in the world’s largest refugee camp.

Repressive Kim Family Rules Isolated North Korea

North Korea is one of the world’s most repressive countries. The Kim family, which has been in power since North Korea’s creation in 1948, bans independent media and tightly controls all information. As a result, society is completely closed off from the world. North Korean state media enforces a cult of personality around its leaders. On its three TV channels, 90 percent of airtime is propaganda devoted to praising the country’s founder, Kim Il-Sung, and misleading North Koreans into thinking their country has a favorable international reputation. North Koreans who challenge these messages face severe consequences, including being sent to secret labor camps that hold as many as tens of thousands of prisoners. The “three generations of punishment” rule then ensures that their children and grandchildren will also face repercussions. The government prohibits leaving the country without permission, but some North Koreans have escaped by crossing the border into China. However, China, which has close ties to North Korea, often sends these defectors back to North Korea, where many face death sentences for attempting to flee.

The Grass Really Is Greener: South Korea’s Vibrant Democracy

South Korea’s vibrant democracy, where people can assemble and protest freely, stands in stark contrast to the North Korean dictatorship. This democratic energy was on full display when South Koreans pressured the president to step down in 2016 in protests known as the Candlelight Revolution. It all started when South Korean media learned that a woman named Choi Soon-sil was acting as then President Park Geun-hye’s close advisor without an official title. Apparently, Choi and Park had accepted bribes from major companies like Samsung, changed university admissions policies to admit Choi’s daughter, and blacklisted academics deemed to be anti-government. (It turned out Choi and her father were members of a spiritual cult and gained this access by convincing Park they could channel communication to her dead mother.) When South Koreans learned about the bribery and corruption, millions poured out into the streets to demand Park’s resignation, lighting candles to symbolize their anger. Park was impeached, and Choi and other complicit officials received lengthy prison sentences.