Geopolitics: Europe

In the aftermath of the Cold War, East-West relations had a chance at a reset.

In the aftermath of the Cold War, East-West relations had a chance at a reset. In a move that remains controversial, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) offered membership to some former Soviet republics and satellite states that sought to join the alliance. Opponents argued the move alienated Russia, but others countered it accelerated countries’ paths to democracy. At one point, Russia itself expressed interest in joining the alliance, but that ultimate concession to the West never materialized. Today, Russian actions in Europe and around the world are again a source of tension. Meanwhile, the European Union (EU) has grown into an influential political bloc with twenty-seven members (excluding the UK, which voted to leave in 2016). It leverages this strength in numbers to drive its agenda on global challenges, like data privacy and climate change, though its members diverge on some foreign policy areas, like their willingness to cooperate with China.

Russian Interventions in Georgia and Ukraine Reignite Tensions

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the end of the Cold War. But tensions between Moscow and Western Europe returned in just a matter of years. In 2008, Russia invaded the country of Georgia to the sharp rebuke of the West. And in 2014, Russia moved troops into eastern Ukraine and seized the Crimean peninsula soon after the country ousted its Russia-friendly president. The move marked the most significant annexation of territory in Europe since World War II, defying the global norm that military force should not be used to change borders. In response, the EU—along with the United States, Japan, and several other countries—imposed economic sanctions on Russia. These sanctions, along with falling oil prices, cost the country billions of dollars, and plunged its economy into a financial crisis. Russia responded with counter-sanctions against Western food imports. Much of those sanctions remain in place to this day amid deep mistrust between Russia and Western Europe.

European Countries Attempt to Save Iran Nuclear Deal

In 2015, six of the world’s most powerful countries signed a landmark deal with Iran that dismantled much of Iran’s nuclear development program in exchange for the lifting of international sanctions. The agreement aimed to slow down Iran’s progress toward building a nuclear weapon, but critics argued that it gave Iran too much in return. President Donald J. Trump—one of the deal’s leading critics—removed the United States from the agreement in 2018 and reimposed sanctions on Iran. European countries objected to this move and in response, created a barter system that allowed companies to skirt U.S. sanctions and continue conducting business with Iran. It’s unclear whether that will be enough to keep the deal alive. Iran has declared its intentions to once again pursue nuclear weapons if the original terms of the deal are not met, a position re-emphasized following the January 2020 U.S. killing of a top Iranian general. Were the Iran deal to collapse altogether, it could ignite a nuclear arms race in one of the most unstable parts of the world.

Emboldened Russia Intervenes in Syrian Civil War

Russian warplanes bombarded several towns across the Syrian countryside in 2015. The airstrikes—Moscow’s first military foray into Syria’s devastating civil war—targeted rebel forces who opposed the country’s oppressive ruler, Bashar al-Assad. The intervention fundamentally shifted the course of the war in favor of the Assad regime. It also marked Russia’s first military intervention in a conflict outside former Soviet borders since the Cold War. Coming just a year after the Crimean annexation, Russia’s involvement in Syria is consistent with a recent trend of Russia reasserting itself in geopolitical affairs. Over the past decade, Russia has backed governments and armed groups in Syria, Ukraine, Venezuela, and elsewhere, often those that oppose the United States and Western Europe. In 2016, the Russian prime minister went as far as to say the world had slid into a new cold war.

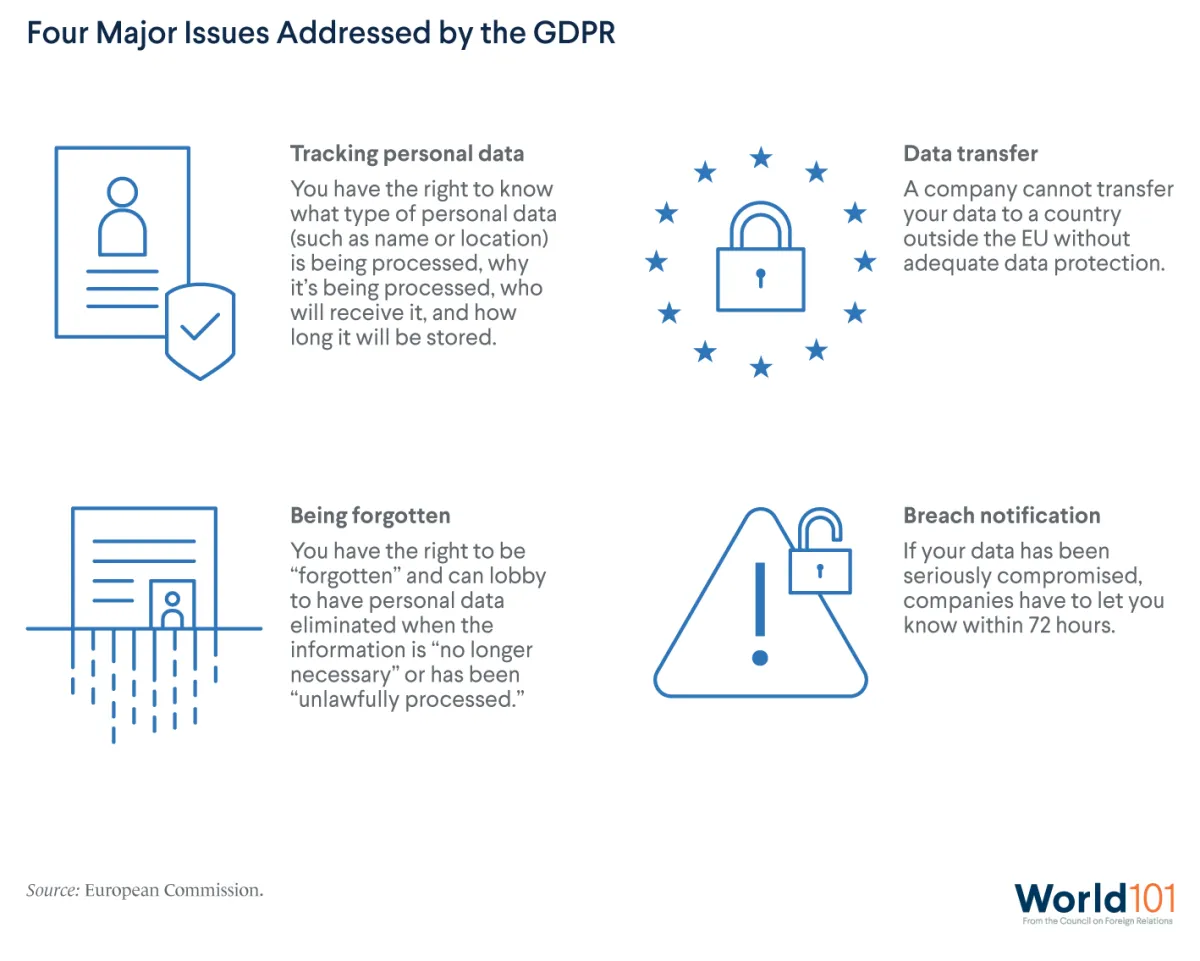

European Union Writes Global Digital Standards

In 2018, the EU implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a sweeping data privacy measure that gives individuals greater control over their personal data. The law applies to all companies that process the data of EU citizens, regardless of whether the company is based in Europe. But the EU hopes to extend these rights to more than just its citizens by limiting access to its market of five hundred million consumers if countries do not meet Europe’s standards. The EU is also standing up to U.S. tech giants like Apple, Facebook, and Google, levying more than twenty billion euros in penalties since 2016 for violating EU competition, tax, and antitrust rules. Their success, however, may be somewhat limited—Google is just too big to be seriously affected by even a multi-billion-dollar fine.

Russia Interferes in National Elections

Since 2015, Russia has interfered in elections in the United States, France, Germany, and the UK, among other countries. This meddling has taken several forms, including promoting disinformation on social media, hacking into campaign email accounts, and channeling funds to select candidates. In so doing, Moscow has sought to promote its preferred candidates and influence the results of national elections. In the UK, for example, Russian Twitter bots allegedly interfered to support the “leave” faction before the Brexit vote. Russia also funds far-right parties in Europe, including a neo-Nazi party in Germany. Although it is unclear just how much Russian interference has swayed these elections, its intentions are incontrovertible and troubling for European—and global—democracy.

Independence Movements Challenge Europe’s Borders

In 2017, millions of Catalans (residents of the semi-autonomous, northeastern corner of Spain) voted to secede and thus become an independent country. The Spanish government in Madrid, threatened by the potential breakup of their country and the loss of a major economic hub in Barcelona, nullified the referendum and arrested the region’s political leaders. Though many think of Europe as a static entity with defined borders, the Catalan independence movement is one of a handful of efforts to redraw those borders. Some movements are entirely peaceful; Scotland held a referendum in 2014 on whether it should leave the United Kingdom. (It decided not to.) Others are more volatile; for years, violence rocked the Basque region in France and Spain. While several of those movements aim for independent territory, many simply seek more autonomy.

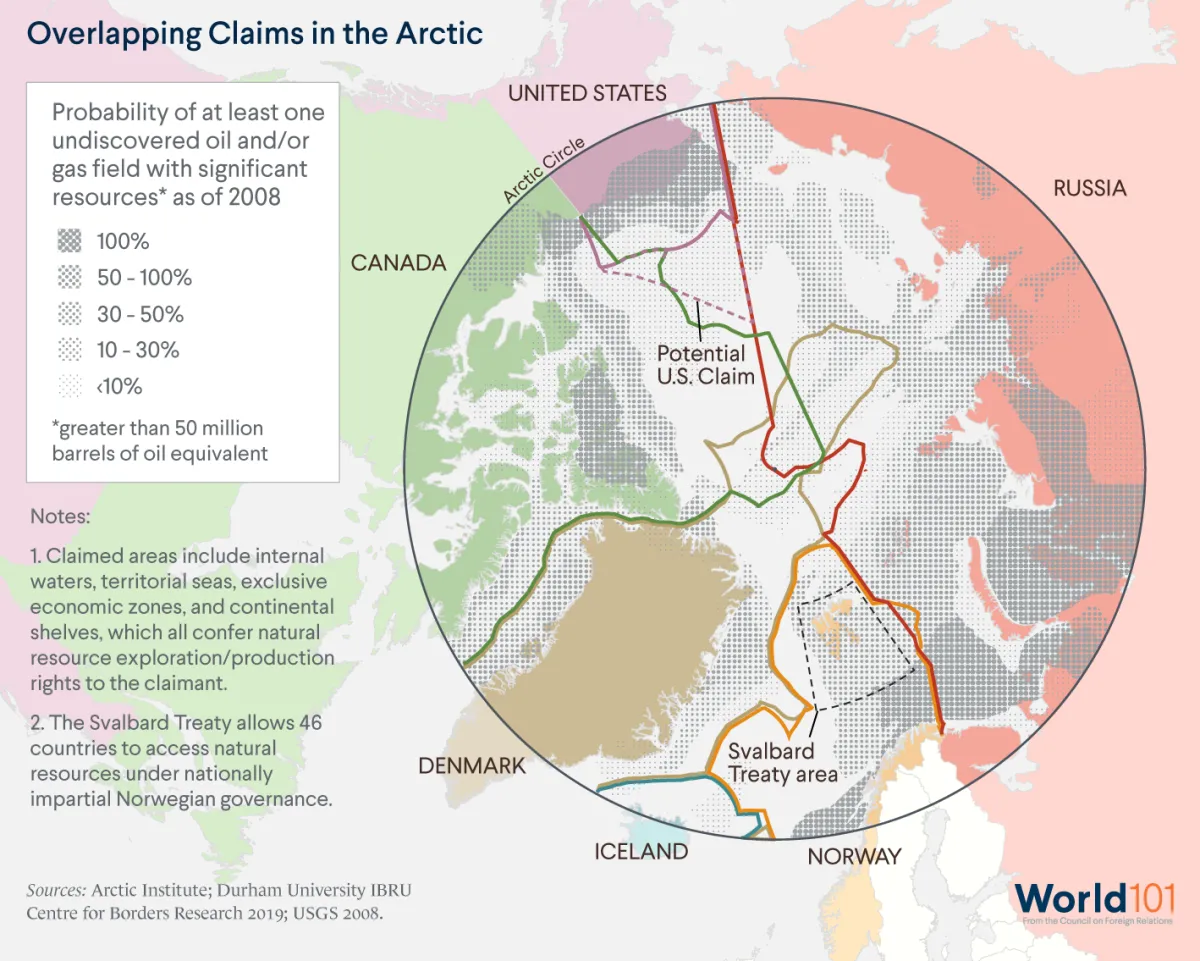

Europe, China Race to Exploit Changing Arctic

The United States, Canada, and six European countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden) control land in the Arctic Circle. For centuries, this largely uninhabited tundra provided little strategic value. But as global temperatures rise and the Arctic remains unfrozen for longer and longer each year, these countries are now racing to establish Arctic shipping routes and extract the region’s potentially vast natural resources, including gas, oil, and rare earth minerals. Moreover, China—despite not actually bordering the Arctic—is investing heavily in energy exploration and infrastructure development in the region. Some, like Russia, welcome China’s outside presence. China needs energy sources, Russia needs buyers for its reserves (especially in light of Western sanctions), and both stand to gain from the relationship. Meanwhile, others—like Denmark and Iceland—view China’s growing presence in the Arctic with more caution, concerned that it could provide Beijing with economic and even military leverage over their countries.

New Geopolitical Circumstances Drive Calls for Unified European Security

Changing conditions within and outside the EU have created a new geopolitical reality. Since 2014, a wave of terrorism has swept Western Europe, Russia boldly annexed Crimea, and the United Kingdom, the EU’s second largest military power, voted to leave the bloc. Meanwhile, U.S. President Donald Trump has criticized Europe’s contributions to NATO, threatening the seventy-year-old security alliance’s continuation. In 2017, in response to these developments, the EU revived its efforts to forge a common defense policy--attempts that date back to the 1950s --through the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) initiative. PESCO would not give the EU power over national armed forces, a level of control that countries have historically resisted. Instead, it creates incentives to pool research and coordinate defensive equipment and technology (European countries use 17 different types of tanks, for example, while the United States uses one). Europe insists it’s not seeking to alienate NATO by stepping up its own defense efforts, but rather to complement it: any PESCO returns can be made available to NATO and UN operations.