Politics: South & Central Asia

South and Central Asia is home to the world’s largest democracy: India.

South and Central Asia is home to the world’s largest democracy: India. Over 600 million people voted in the country’s most recent elections. But large democracies do not necessarily translate into healthy democracies. In India, corruption and a rising trend of religious nationalism threaten the country’s democratic and secular foundations. Next door, Pakistan—nominally a democracy—struggles to balance power between the elected civilian leaders and the military and intelligence agency. Meanwhile, Central Asia’s governments are mostly autocratic and some of the most repressive regimes in the world. Leaders there have ruled for decades by locking up political dissidents and leaving no room for civil liberties like freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

India: The World’s Largest Democracy

India is the world’s largest democracy with nine hundred million eligible voters, more than three times that of the United States. Compared to the United States, which has just two parties in Congress—and a handful of independent members—India has more than thirty parties with seats in its parliament and another 2,300 vying for representation at the local and state levels. Most Indians say they are satisfied with their democracy, but Indian democracy has its share of problems. Although elections are generally well run, free, and fair, politicians are frequently accused of corruption and bribery. Almost half of India’s newest members of parliament in 2019 face criminal charges. The large number of parties in India’s parliament also makes decision-making slow, and many rank the country’s bureaucracy as one of Asia’s most excessive and sluggish.

Hindu Nationalism Challenges a Secular India

The drafters of India’s constitution envisioned a diverse, multicultural country where religious minorities like Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians would be treated equally. Early Indian governments passed laws to protect minority rights and promote this Indian version of secularism, but those who disagree with this multicultural view have gained power in recent decades. These Hindu nationalists believe the government should prioritize the interests of Hindus, who make up 80 percent of the Indian population. These nationalists oppose what they view as government concessions to Muslims, like banning books deemed offensive to Islam and allowing Muslims to use Islamic law for marriage and inheritance. And their tactics have sometimes been violent. Extremist Hindu nationalist mobs demolished a mosque said to be built on the site of a Hindu temple and have beaten to death Muslims accused of illegally slaughtering cows, which are sacred in Hinduism. They also lobbied the central government for years to revoke the special status of Kashmir—India’s only Muslim-majority state—that has allowed the state to remain relatively autonomous and largely prevented non-Kashmiris from buying up land in Kashmir. After sweeping recent elections, pro-Hindu nationalist lawmakers finally revoked Kashmir’s autonomy in 2019 and passed a law making it easier for non-Muslim immigrants from certain countries to become citizens, placing the country’s secularism at risk.

Pakistan: A Democracy, or One in Name Only?

In Pakistan, the people elect the politicians, but the country’s military holds the real power. The military’s intelligence agency, known as the Inter-Services Intelligence, is particularly influential: it has consistently manipulated elections and staged coups under the pretext of protecting the country’s national interests. This, in turn, has eroded the public’s faith in its democratic institutions in addition to rampant corruption and frequent scandals. What’s more, it was not until 2013 that Pakistan had its first transfer of power between two civilian leaders. This tense civil-military relationship makes Pakistan unpredictable and a difficult strategic partner for countries such as the United States.

South Asian Democracies Are New and Fragile

The twenty-first century has seen a wave of democratization in several South Asian countries. Both Bhutan and Nepal—former monarchies where kings ruled with absolute power—introduced democratic elections over the past two decades. The Maldives, likewise, held its first competitive elections in 2008, following thirty years of dictatorship during which torture and arbitrary imprisonment were commonplace. Even Afghanistan now holds presidential elections, just years after the Taliban government was overthrown. But persistent challenges threaten to unravel these fragile democratic achievements. Afghanistan’s elections are frequently marred by violence and accusations of fraud. The government in the Maldives still requires its citizens to be Muslims, barring religious minorities from holding political office. And in Bangladesh, a once-vibrant democracy is giving way to single-party rule as the government arrests journalists, restricts free speech, and silences political dissent—all while the party swept recent elections with over 80 percent of the vote.

Autocracies Hold Strong in Central Asia

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, many experts in the West expected democracy to take hold in the former communist countries. But things did not exactly turn out that way. Today, Central Asian countries are some of the world’s most authoritarian and are making little progress toward becoming open, democratic societies. Elections are either nonexistent or blatantly rigged. For example, in Turkmenistan’s 2017 presidential election, the incumbent president won 98 percent of the vote. And although Kazakhstan’s president of twenty-nine years stepped down in March 2019, he handpicked his successor, who received over 70 percent of the vote in the election that followed. Kyrgyzstan is bit of an outlier among the Central Asian countries, with a freer and fairer election than those of its neighbors in 2017.

Central Asian Governments Suppress Civil Rights and Liberties

Central Asia has practically no room for political dissent or activism. Leaders in almost every Central Asian country have intimidated, imprisoned, and exiled political opponents. In Uzbekistan, for example, the government has jailed at least ten thousand political prisoners over the last decade. Meanwhile, in Kazakhstan, a man decided to test free speech in his country in 2019 by conducting a social experiment: He went to a town square and held up a completely blank sign. He was immediately arrested. Governments also tightly control media and are quick to ban platforms like Facebook and Twitter on the rare occasion that protests do break out. But this control is not all about security: Tajikistan’s president temporarily banned YouTube in 2013 after an embarrassing video of him poorly singing karaoke at his son’s wedding went viral.

Authoritarians in Central Asia Tighten Control Amid Health Crisis

Authoritarian governments across the world have used the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity to consolidate their power. In Central Asia, leaders have targeted journalists, activists, and other political opponents under the guise of essential emergency pandemic measures. In Kazakhstan, activists have criticized the parliament for rushing through new legislation further limiting the right to protest, while in Kyrgyzstan the government has been able to hold hearings on an anti–nongovernmental organization law without demonstrations from the affected groups due to COVID-19 restrictions on gatherings. Several leaders in the region have also downplayed—or outright denied—COVID-19 infection and death rates in their countries in an effort to minimize public unrest, which could challenge their authority. Tajikistan, for example, did not confirm its first case until April 30, 2020, while Turkmenistan, an authoritarian country with a long record of government censorship, has yet to report a single infection as of September 2020.

A Region Wracked by Terrorism

Over the past decade, more terrorist attacks have happened in South and Central Asia than anywhere else in the world. Pakistan is at the center of much of the region’s terrorism. It’s both one of the worst-affected countries in the region (its Shia and Ahmadi religious minority groups are particularly vulnerable) and home to the leadership of many Islamic extremist groups, including the Afghan Taliban, which has killed tens of thousands of civilians in Afghanistan. Security experts believe that the most likely scenario that could trigger the use of nuclear weapons in South Asia would involve a terrorist attack in India traced back to or claimed by a Pakistan-based group. Terrorists from Pakistan are India’s gravest security threat from abroad. A few years ago, a former Indian prime minister stated that the greatest internal security threat came from an insurgency by the Naxalites, a leftist group whose guerrilla attacks have killed thousands in the east of the country. Elsewhere, the self-proclaimed Islamic State and other Islamic extremist groups have carried out high-profile attacks in recent years, notably in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

Pakistan-Based Terrorist Group Inflames Regional Tensions in “India’s 9/11”

In 2008, India suffered one of the deadliest terrorist attacks in its history. Members of an Islamist terrorist organization launched twelve coordinated strikes targeting the most iconic areas of Mumbai, killing nearly two hundred people. Because the terrorists originated from Pakistan and received support from former Pakistani army and intelligence officers, relations further deteriorated following the deadly incident. India made numerous military threats against Pakistan and ended peace talks over Kashmir and other security issues. The “26/11 attacks,” in reference to the date November 26, are also sometimes called “India’s 9/11.” Similar to the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, the terrorist attack in India made national security a top government priority and directly led to increased training for military officers and greater intelligence-sharing with the United States.

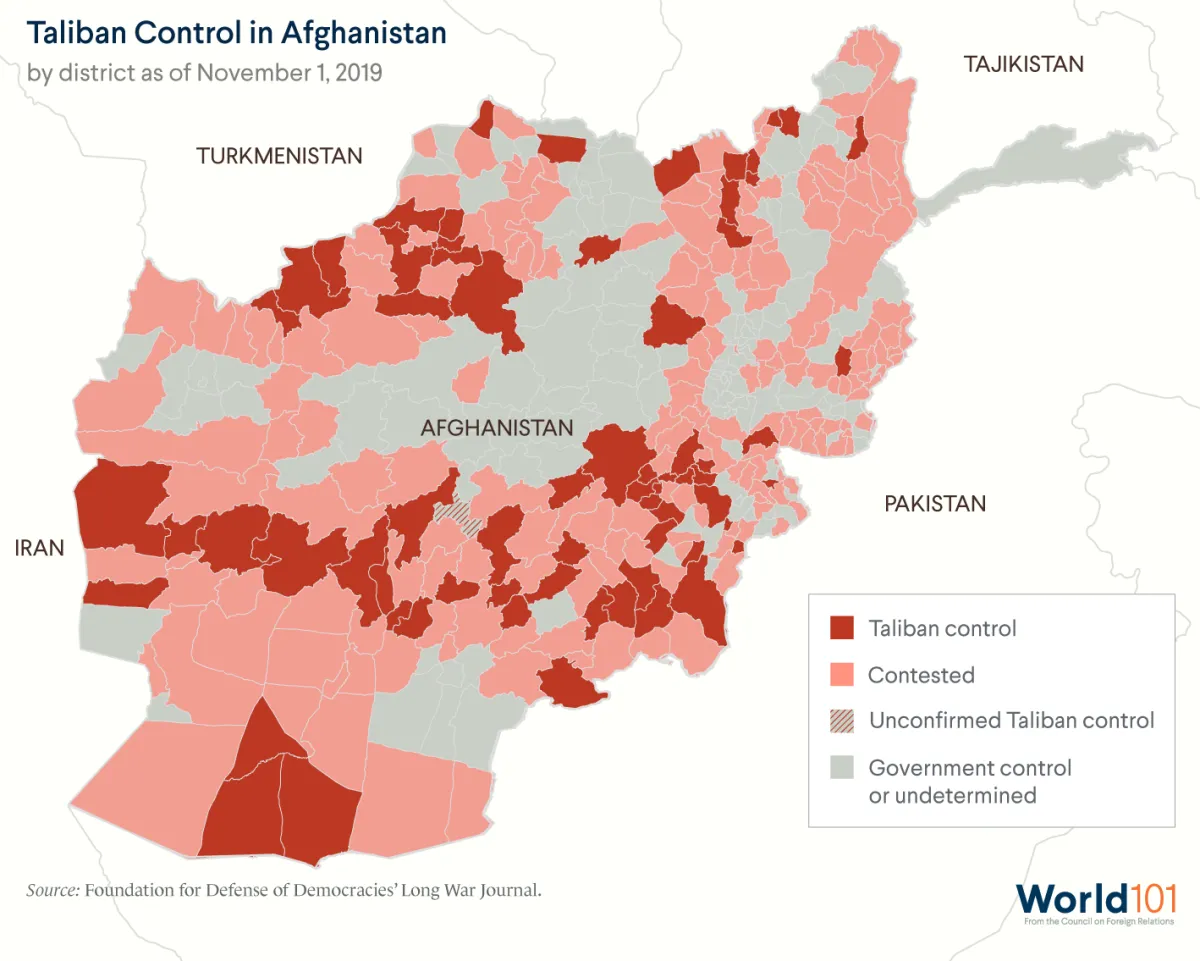

The Taliban and the Troubled Afghan-Pakistani Border

The Taliban is an Islamic fundamentalist group, comprising mostly Pashtuns, Afghanistan’s largest ethnicity. They ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001, using extreme violence to enforce their idea of an Islamic state. Less than a month after the 9/11 attacks, the United States invaded Afghanistan to bring down the Taliban government, which gave refuge to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda, perpetrators of the attacks. But nearly two decades later, the Taliban still controls much of the country and is responsible for thousands of attacks and suicide bombings in an ongoing insurgency against Afghanistan’s U.S.-backed central government. Fighting has spilled over into tribal Pashtun areas of neighboring Pakistan where the Taliban receives support, making the Afghan-Pakistani border one of the most unstable and dangerous borders in the world. Despite multiple rounds of peace talks between the United States and the Taliban, negotiations have yet to bring a political resolution to the conflict.