Understanding Revolutions

Explore the powerful political movements that can reshape forms of government.

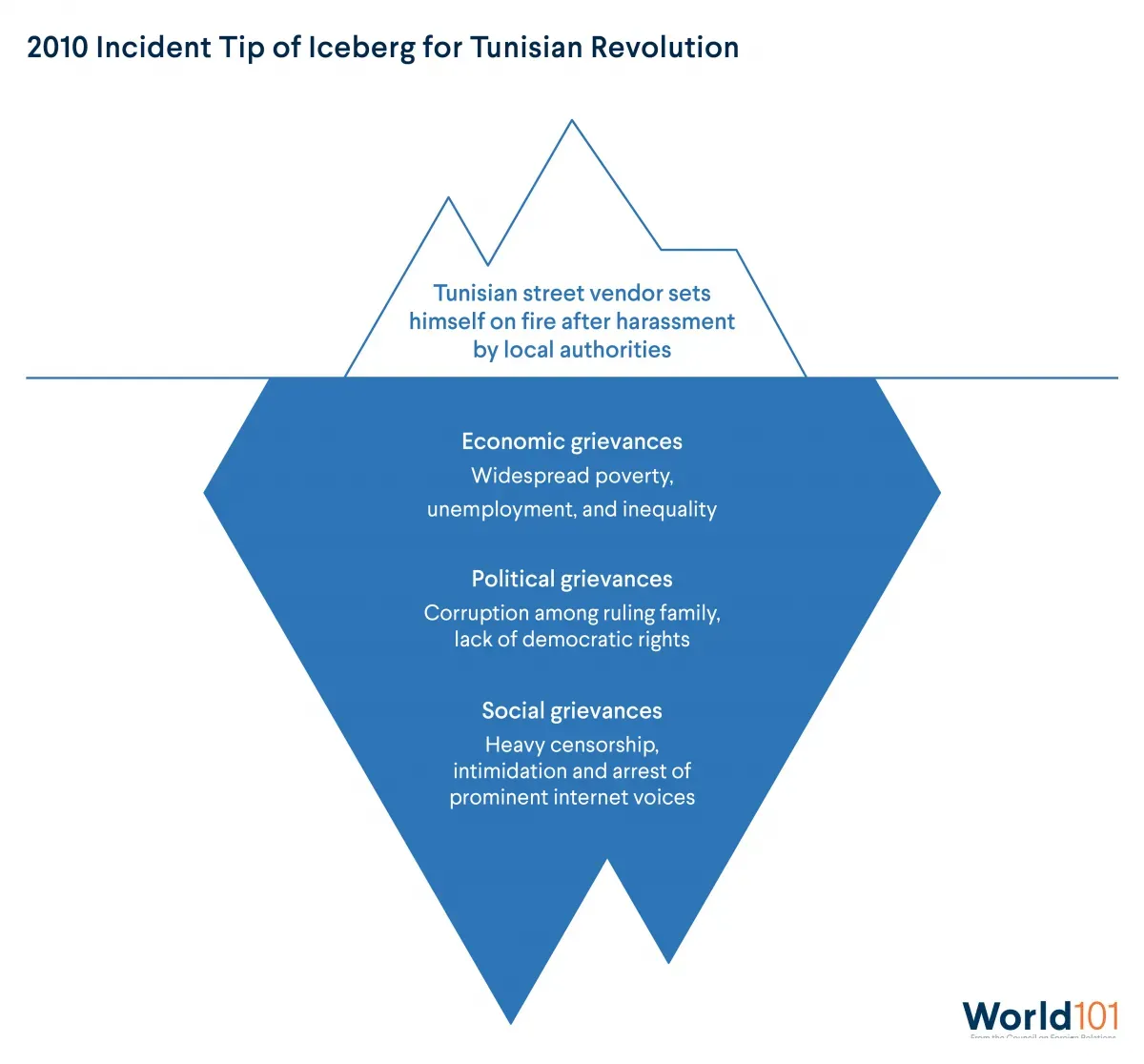

On December 17, 2010, a Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after the police confiscated his fruit stand.

His self-immolation struck a chord with young people around the country and throughout the Middle East. Within days, protests erupted around the region, from Syria to Egypt and Libya. Millions demanded economic, political, and social reforms from governments that were chronically unresponsive to their needs. Such shows of civil disobedience had been extremely rare in these countries, where authoritarian leaders forbade political dissent.

But despite taking place at the same time and in neighboring countries, those revolutions—collectively referred to as the Arab uprisings, or Arab Spring—took dramatically different directions. Tunisia successfully ousted its longtime dictator and transitioned to a democracy. Libya, Syria, and Yemen descended into devastating civil wars, some of which are ongoing. In Egypt, citizens voted in the country’s first free and fair election in 2012. However, a counterrevolution in the following year installed yet another military regime that persists to this day.

Revolutions come in all shapes and sizes. At their core, they are mass mobilizations that simultaneously overthrow both the government and the social structures that support the political system. As a result, revolutions usher in rapid and significant change to a society. Those powerful political movements can potentially reshape a government and a country’s standing in the world. The United States, France, and Haiti, for example, are all products of eighteenth-century revolutions inspired by calls for greater individual rights and freedoms.

Revolutions are not automatically good or bad. They can free people from the grip of foreign powers or a repressive government and usher in an era of economic prosperity and political stability. Alternatively, they can lead to greater disorder and chaos. Following a revolution, an even more brutal regime could take the place of the ousted government.

This resource explores a revolution’s defining characteristics to help make sense of the next movement that challenges a ruling authority.

What Drives Revolutions?

Why did so many people across the Middle East participate in the Arab uprisings? In Tunisia, protesters demanded “the fall of the regime.” In Egypt, demonstrators called for “bread, freedom, and social justice.” Although those slogans make for memorable rallying cries, all the reasons revolutions start would never fit on a poster. Instead, they are rooted in deeper economic, political, and social grievances.

Economic Grievances

Bouazizi set himself on fire because the government confiscated his sole source of income: his fruit stand. Widespread poverty and unemployment are common drivers of unrest. This is especially true in countries with high inequality like Tunisia, where select individuals with personal ties to the government amass immense wealth. Meanwhile, the vast majority of the citizenry live in poverty.

Political Grievances

Many authoritarian countries limit participation in politics. Some countries do not hold elections, while in others elections are neither free nor fair. For example, Muammar al-Qaddafi—Libya’s dictator of forty-plus-years—ruled the country with unchecked power. Al-Qaddafi suppressed civil liberties and imprisoned political opponents until his ouster in the country’s 2011 revolution.

Social Grievances

Conditions that reduce a population’s security—for instance, discrimination, persecution, or a lack of opportunities— often create tensions. Government oppression is another factor. In Syria, protests demanding the fall of the country’s dictator erupted in early 2011. Outrage spread after government security forces arrested and tortured a group of teenage boys who had written anti-regime graffiti on a school wall.

What Influences the Outcome of a Revolution?

Some revolutions begin suddenly, taking rulers by surprise, ousting a regime, and resulting in dramatic political change. Others go on for years and end with the government and revolutionaries at the negotiating table, perhaps agreeing to reforms such as a power-sharing agreement. Still, others are stopped short. Revolutions can end with the existing government resuming control—often after brutal crackdowns.

Why are some movements successful in overthrowing their government while others fail to do so?

In some countries, the government can restrict, monitor, and censor social media, which prevents demonstrators from gathering and helps rulers target political activists. Such restrictions can be effective in deflating protest movements. In 2019, Iran’s government shut down the internet for a week amid countrywide protests. The internet shutdown made organizing demonstrations more difficult and hampered news reporting on the situation.

In certain instances, governments attempt to crush protest movements with forceful crackdowns. Egyptian security forces, for example, killed hundreds of their fellow citizens during a 2013 demonstration that challenged the country’s new military regime. But what happens if the military refuses to fire on protesters and instead stands in solidarity with revolutionaries? In such instances, the government is left largely powerless. This was the case when the Tunisian military supported the country’s protest movement during the Arab uprisings.

Successful movements need to agree on aims. Anyone who has worked on a group project in school knows the difficulty of managing expectations, the workload, and the outcome. When revolutionaries can’t agree on goals and how to accomplish them, they risk splintering into a patchwork of movements, often with competing agendas. That was the case in Syria, where scores of different rebel groups took up arms against the country’s government. Revolutionaries could not agree on what a political settlement should look like.

Factors outside the country altogether can also determine a revolution’s success or failure. Intervention by foreign countries—either in favor of the government or the protest movement—can make or break a revolution. Countries such as the United States, Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey intervened in Arab uprisings with money, weapons, and diplomacy. Foreign actors have participated in revolutions hoping to sway the outcomes in countries including Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Syria, and Yemen. Some of those conflicts drew so much foreign intervention they became proxy wars. This type of conflict occurs when foreign countries with competing interests battle it out by supporting opposing sides in an otherwise domestic conflict. In other instances, outside intervention quickly quelled revolutions. Such an instance occurred when Saudi Arabia sent troops into Bahrain in 2011.

What Are the Foreign Policy Effects of a Revolution?

Revolutions that take place in one country often reverberate well beyond that country’s borders.

Revolutions can inspire like-minded movements across the world, just as the slogan of the Tunisian revolution—the people want the fall of the regime—echoed throughout the Middle East. Post-revolution governments can even support groups in other countries that share their goals and ideology. The Soviet Union did so extensively throughout its history. Moreover, Iran has been sanctioned for attempting to export its 1979 revolution to the rest of the Middle East.

Cuba—another country that has historically supported revolutions around the world—is also an example of how a revolution can have dramatic foreign policy implications. The island country was once a close economic and political ally of the United States, but revolutionaries saw the United States as a supporter of the regime that oppressed them. After the 1959 revolution, the new Cuban government cut all ties with the United States. The communist regime in Cuba instead developed close relations with the Soviet Union.