Geopolitics: South & Central Asia

The long tensions between India and Pakistan, involvement of foreign powers, and climate change shape geopolitics in the region.

Former U.S. President Bill Clinton once described the India-Pakistan border as “the most dangerous place in the world.” Since their independence, India and Pakistan have fought multiple wars, two of them over the contested territory of Kashmir. Their border remains one of the most heavily militarized places in the world. Moreover, because both countries have nuclear weapons, another conflict could be catastrophic. Pakistan has always viewed the much larger India as an existential threat, but for India, Pakistan is just one of two worrisome neighbors: the other is China. As China reinforces its alliance with Pakistan, and its presence in the Indian Ocean expands, India has begun to strengthen its own regional partnerships. Overall, the region faces significant problems—notably climate change, which threatens to displace millions of people in low-lying countries like Bangladesh and the Maldives—but the lack of strong regional organizations like the European Union or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations has made solving these issues that much harder.

India-Pakistan Rivalry Defines Region

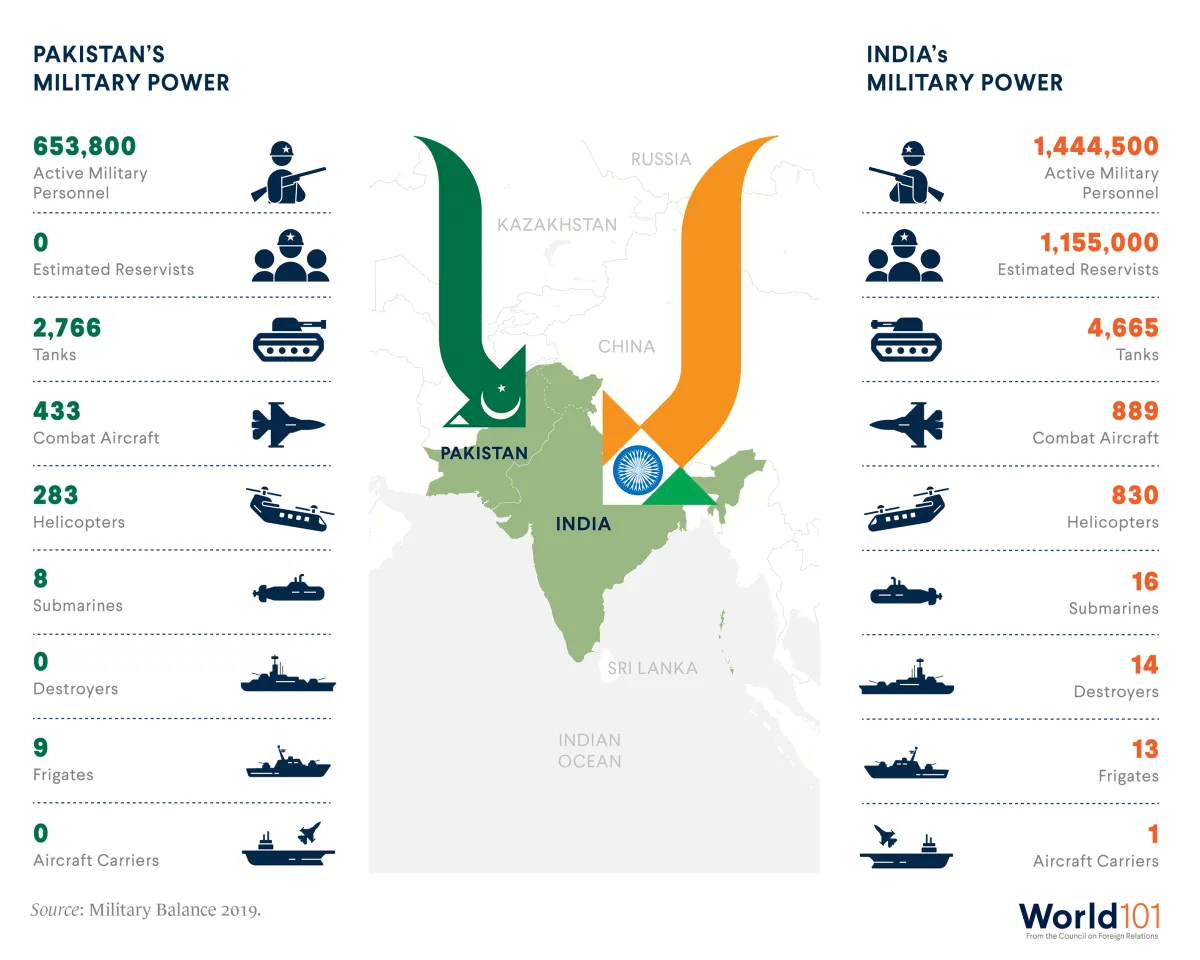

India’s military is one of the world’s largest in terms of personnel strength and dwarfs that of its neighbor and rival, Pakistan, by almost every measure. But nuclear weapons serve as the one equalizing factor. The two countries have comparable nuclear arsenals, which dramatically raise the stakes of any direct confrontation. Tensions are highest in the disputed territory of Kashmir, where hundreds of thousands of troops on both sides are stationed along the Line of Control that forms the de facto border. India and Pakistan have clashed here several times before, and flare-ups continue to occur along the border, as recently as 2019 after a terrorist attack by a Pakistan-based group targeted Indian police.

High Stakes in Conflict Over Kashmir

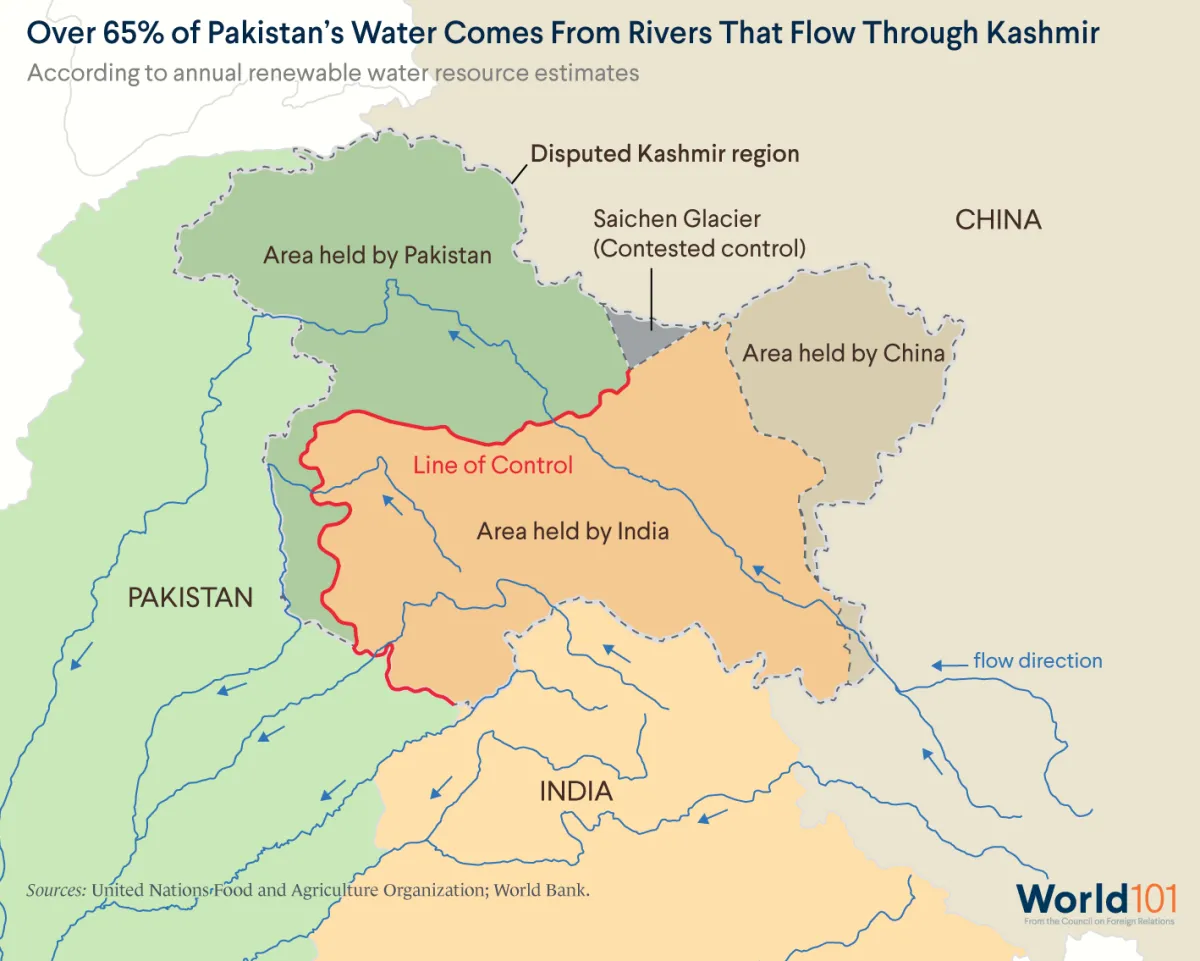

India and Pakistan have fought two wars over Kashmir, yet no resolution is in sight. Control over this Himalayan territory is so important for primarily symbolic reasons. Historically, India has wanted to show that its secular democracy can protect the rights of Muslims, who are the majority in Kashmir. Meanwhile, for Pakistan, Kashmir is vital to its national identity as a homeland for Muslims in South Asia. The issue of water is also important. Hundreds of millions of people rely on the rivers that flow from Kashmir, and both India and Pakistan are eager to control this water source. Soldiers from both sides have fought and died over this territory, which remains at the core of the seven-decade animosity between India and Pakistan.

Insurgency Creates Added Layer to Kashmir Conflict

In the 1980s, opposition groups in Indian-controlled Kashmir accused the government of rigging local elections. Violence erupted as insurgents, using weapons provided by Pakistan, killed hundreds of government officials. This movement involved an Islamist element as well, with insurgents targeting Kashmir’s Hindu minority. Since then, the Indian army has stationed thousands of troops in Kashmir to maintain security. But according to human rights groups, the Indian army has used excessive force. Hundreds of demonstrators accused of rioting or throwing rocks have been blinded by Indian soldiers firing on them with pellet guns. The situation deteriorated further in 2019 after the Indian government revoked Kashmir’s special status as a semiautonomous region, which it had maintained since joining India in 1947. The government’s move sparked widespread protests and added to the deep mistrust between the Indian government and Kashmiri youth, many of whom now view India as an occupying force.

A Region Rife With Conflict Lacks Forum for Peace

In Southeast Asia and Europe, countries have promoted security and prosperity through strong regional institutions, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the European Union. In South Asia, however, these institutions are virtually absent largely owing to the rivalry between India and Pakistan. One organization, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), was established in 1985 to promote economic growth and democracy across South Asia, but it has hardly any influence and has in recent years stopped meeting regularly. In fact, half of its members, including India, boycotted a recent SAARC summit that was to be held in Pakistan, accusing Pakistan of promoting terrorism and meddling in their domestic affairs. The lack of meaningful integration means the region is missing out on cooperation that could boost development and peace.

Regional Security Alliance Keeps Russia Close

Central Asian countries are no longer part of the Soviet Union, but Russia still provides security for many of them. In 1992, Russia joined Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan to form a military alliance now called the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which was built on the promise of mutual security, or the obligation to come to another member country’s defense if it is attacked. The CSTO allows Russia to keep close ties with the former Soviet republics in Central Asia as well as help smaller countries like Tajikistan secure their borders.

India’s Foreign Policy Defies Traditional Alliances

Throughout the Cold War, many countries aligned themselves either with the United States, the leader of the so-called Western Bloc, or the Soviet Union, the leader of the Eastern Bloc. But India, among others, proposed an alternative, by helping to establish the Non-Aligned Movement, whose members pledged to be neutral in the great power struggle that defined the Cold War. India has continued this principle of foreign policy independence ever since, which allows it to work with countries that are often at odds with one another. While India has grown closer to the United States in recent years, it continues to be Russia’s largest weapons customer and finances infrastructure projects in Iran. And although India competes with China, it still considers the country to be a strategic partner while also trading with China’s neighbors like Japan and Taiwan. India still factors in Pakistan when making foreign policy decisions, but it continues to avoid formal alliances.

India Uses Foreign Aid to Keep Friends Close

India has transitioned from an aid recipient to a donor as its economy has grown over the last decade. It’s now one of the largest donors to Afghanistan, which India sees as an important partner given Afghanistan’s strategic location bordering Pakistan. India also bankrolls energy infrastructure in Bhutan and Nepal. But the aid is not just about charity. Like other donors, India uses foreign aid to promote its national interests. India wants to maintain its status as the region’s most influential country—a position that’s increasingly under threat as China makes more friends in South Asia and around the Indian Ocean. This power struggle was on full display in 2012, when India withdrew some aid to Bhutan after Bhutan’s prime minister met China’s leader. And a planned BRI-funded railway project between Nepal and China, if successful, could potentially reduce Nepal’s long-standing reliance on India.

In India’s Neighborhood, Chinese Presence Grows

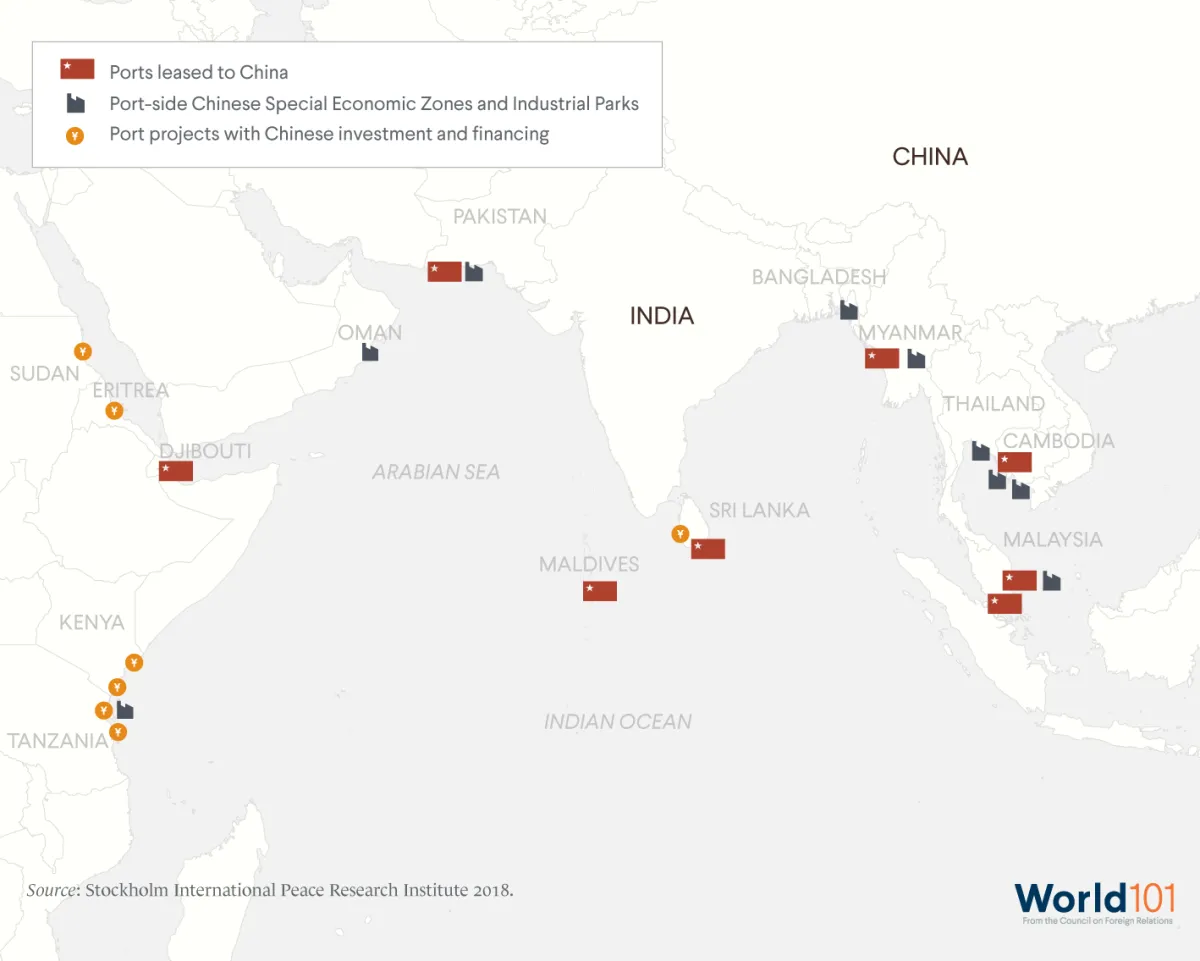

On land, India’s main competitor is Pakistan. But at sea, it faces an even stronger rival: China. India and China’s tense relations have roots in border disputes in the Himalayas, and the two fought a war over it in 1962. But China has also recently been increasing its presence in the Indian Ocean, which India views as traditionally its area of influence. China has created a chain of projects sometimes known as the String of Pearls, including ports in several countries that neighbor India, and it’s sent aircraft carriers through the Indian Ocean to protect Chinese interests. China insists its activity in the Indian Ocean is purely commercial and that these projects are part of the Maritime Silk Road under its Belt and Road Initiative, but many Indian and U.S. observers are skeptical. China’s close economic and military relationship with Pakistan has particularly worried India, which sees the increased Chinese presence from all sides as a threat to India’s power in the region.

Climate Change Leaves South Asia Vulnerable

Climate change and extreme weather conditions pose grave threats around the region known for its dense cities and populous coastlines. Cyclones, like the one in Bangladesh in 1991 that claimed over 140,000; heat waves, like the one in India in 2015 that killed more than 2,500 people; and other disasters like floods and droughts are increasing in frequency as the earth’s atmosphere warms. The human cost of these climate disasters is high, as is the financial cost, which threatens to disrupt the region’s economic growth. Bangladesh is especially vulnerable. It is the size of Iowa and yet has a population of more than half the size of the United States. With sea levels rising, this densely populated country is at risk of being underwater in just a few decades. Estimates warn climate change could create up to thirteen million Bangladeshi climate refugees and forty million internally displaced people by 2050.

Saving the Maldives From Rising Sea Levels

Climate change is a threat to the entire planet, but it’s particularly immediate for the people of the Maldives. The Maldives is an Indian Ocean country made up of 1,200 islands and, at just a few feet above sea level, is the lowest-lying country in the world. Even minor sea level rises threaten to submerge the entire country and its more than 400,000 residents. The Maldives has experimented with adaptive technology, such as building artificial islands, but that might not be enough. The situation is so precarious that then President Mohamed Nasheed had announced a plan in 2008 to buy land in India, Sri Lanka, or Australia to relocate the entire Maldivian population. Though the new government has all but abandoned that plan, the Maldives remains a symbol of the threat of climate change.