What Kinds of Governments Exist?

And what do we learn by categorizing them?

One of the world’s earliest known works of literature is a poem about a king named Gilgamesh, who ruled a civilization in ancient Mesopotamia. King Gilgamesh oppressed his people, and in turn, they appealed to the gods for help. He was supposed to be their “shepherd” and “protector,” but they claimed he was falling short.

Almost four thousand years later, all governments continue to share the same basic traits: they aim to lead and protect their people.

But identifying what, exactly, they are protecting their people from is where the differences start to emerge. Do they consider foreign invasion or internal violence to be the bigger threat? Are they more interested in eliminating poverty, creating safeguards against state oppression, or merely holding on to power?

How governments interpret, prioritize, and grapple with pillars of modern society—for instance, security, freedom, and prosperity—determines the kinds of policies they enact.

Those simple-sounding ideals belie big concepts; terms like prosperity mean different things to different governments. Some define prosperity as creating conditions where individuals are free to maximize profits; however, that scenario can result in a less equal society. Others understand a society to be prosperous when every person is entitled to a certain share of resources—such as wages, health care, or shelter. In that version, inequality is tightly controlled. However, some citizens can decry the lack of individual freedom.

Those various priorities manifest in different kinds of governments. By thinking about how we categorize those governments, we can better understand what kind of society they aim to govern. Because governments are multidimensional, it’s useful to ask a series of questions.

Who leads the government?

King Gilgamesh was accountable to no one but the gods. Other leaders answer to the entire citizenry. This accountability exists in the form of regularly scheduled democratic elections.

Those types of votes happen in democracies, in which citizens determine who will govern them. At its core, democracy simply means that the people make decisions, often through representatives whom they elect. Democratic governments create laws and institutions to protect people's ability to express their will: they guarantee free and fair elections, free speech, and the right to assemble and protest. Certain measures ensure power remains dispersed. Democracies typically feature checks and balances among multiple branches of government and a free press.

Most democracies are also associated with political equality with each citizen entitled to one vote. This is known as universal suffrage.

In authoritarian governments, meanwhile, power is concentrated in the hands of the few—often one political party or even a single leader (this is known as an autocracy). Authoritarians go by many names: monarch, dictator, and even prime minister or president. What distinguishes those governments are not titles but practices.

An authoritarian government is interested, above all else, in preserving its power. Because civil disorder can lead to revolt, such governments tend to emphasize order. Individual freedoms such as free speech (including protests) and the right to privacy are often curtailed in the process. Authoritarian governments entertain few or no checks from elsewhere in government. Leaders are not constrained by a legislature, the court system, the media, or civil society (organizations and businesses outside government).

Those practices play out in authoritarian governments around the world. The Chinese government violently suppressed the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests because it believed they endangered Chinese Communist Party rule. In 2020, China passed a law restricting protests in Hong Kong. Couched in the language of security and stability, the law likens some forms of protest to terrorism. The government also monitors online activity, censoring any mention of the Tiananmen massacre. China also has an extensive track record of removing online content deemed too critical of the government.

Authoritarian countries like China often defend their form of government by arguing that they can efficiently provide sustained economic growth. They suggest that democratic governments can guarantee certain freedoms but struggle to pass laws and promote economic growth due to political gridlock. Although authoritarian governments can generally enact economic policies more easily than democracies, their lack of political accountability can slow their ability to correct failing and harmful policies. China, for example, took over three decades to end its highly criticized one-child policy. Democracies, meanwhile, are often self-correcting and tend to move away more easily from misguided or unpopular policies. Many democracies like the United States have also created unprecedented economic growth.

What is the relationship between the government and the economy?

Some people believe a prosperous country is one in which everyone shares in the benefits. Others believe the government’s responsibility is to leave each individual to pursue maximum prosperity—even if that means some are left behind.

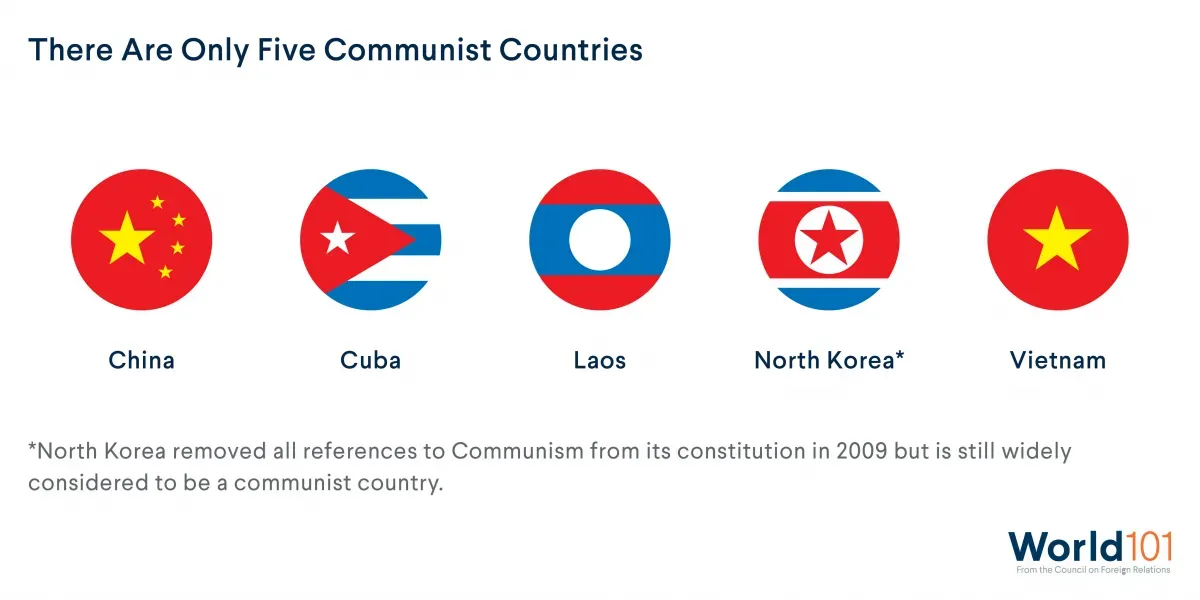

An economy in which the government makes all economic decisions owns the largest companies and allocates the country’s resources would be at one end of the spectrum, one in which the government stays out of the economy entirely and leaves everything to the private sector would be at the other end. The first can be considered a communist system (though that label also carries political, not just economic, implications). The latter is a capitalist system.

In a communist system, the government exerts maximum control. Private property is eliminated in favor of equal public ownership of the means of production (such as factories), natural resources, and more. In a purely capitalist system, private citizens—not the government—control production. This means that individual citizens own businesses, factories, and farmland for agriculture. They trade in a largely unregulated economy in which market forces—the laws of supply and demand—rather than the government set prices. Socialist systems fall somewhere between these two poles, but they can be notoriously difficult to define. Many socialist systems have public control of production and extensive government welfare programs. However, such public control often exists alongside elements of a free market, including ownership of private property.

Put simply, those systems envision different kinds of societies based on who controls production—businesses, factories, and agriculture—and property. Governments that lean toward more control tend to emphasize equality. Maybe they guarantee everyone a job, set salary caps for the highest earners, or ensure a minimum wage for all workers. Governments that leave more economic decisions to citizens emphasize freedom, imposing few restrictions on how much (or little) money people make and how they make it.

In reality, most governments fall somewhere within that range rather than at either pole. None is purely capitalist; even minimally, all governments are involved in economic decisions. That involvement can take the form of providing unemployment insurance. Government intervention also occurs when regulating competition (such as with antitrust laws) to ensure no single company can establish a monopoly. The United States, for example, is considered a capitalist country, but the government is responsible for constructing roads and other infrastructure that allow businesses to function. The U.S. government also designs regulations to create safe workplaces.

Similarly, few governments are fully communist. China features an economic model that blends private entrepreneurship with government influence over many industries. Cuba, another famously communist country, relies on foreign investment from capitalist countries to sustain its economy. In 2019, the Cuban government reformed its constitution to legalize private businesses.

What is a government’s political ideology?

Political ideology is another way of characterizing how a government views its role in society.

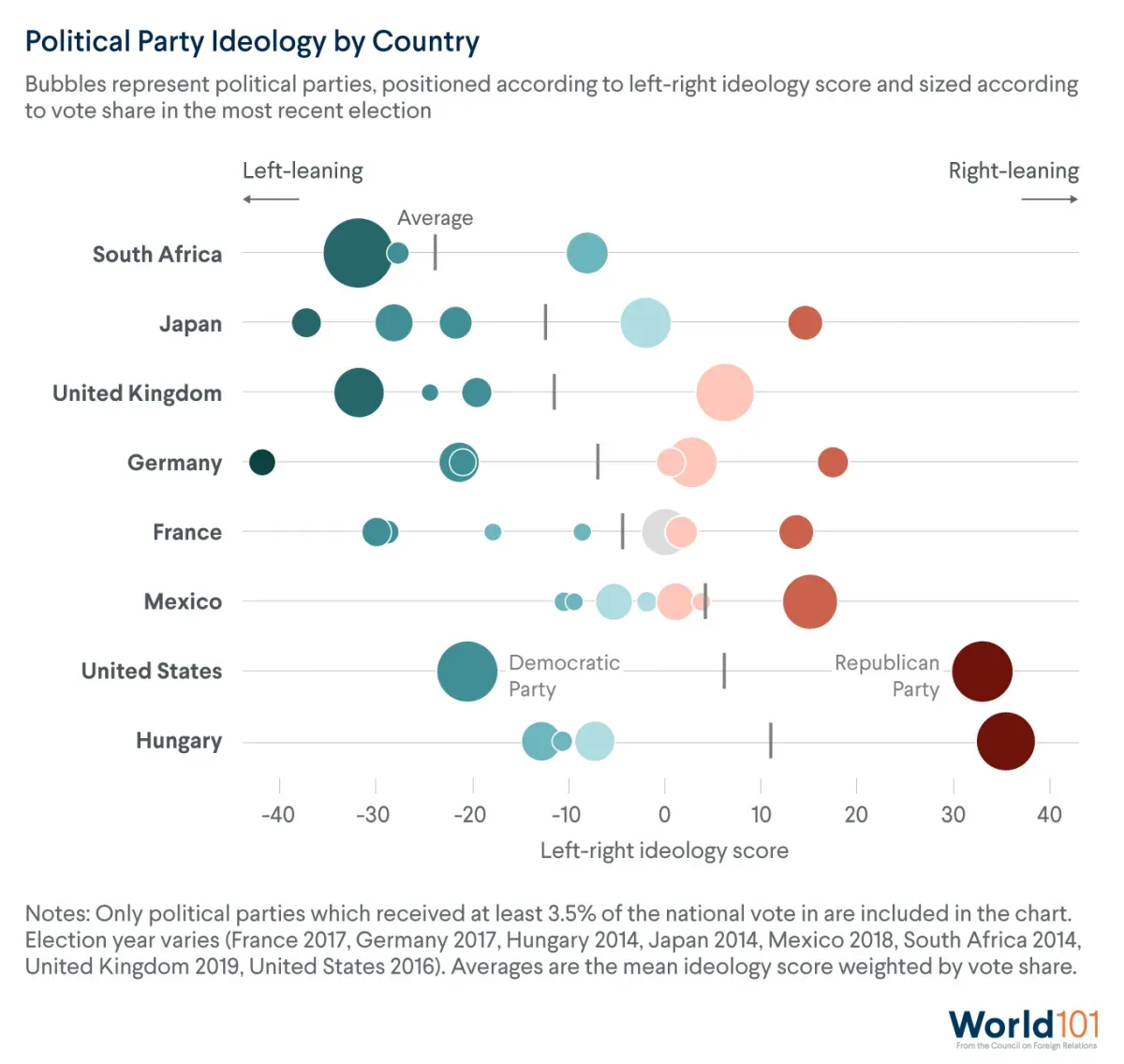

Left-wing, also known as liberal, governments work toward achieving social equality. They view the government’s role to be providing more people with prosperity (whether that means more money, protections, or opportunities) to make society more equal. Many such governments today support strong social safety nets. These programs, including government-provided health care and unemployment insurance, exist to protect society’s most vulnerable citizens. In theory, left-wing governments support large and often rapid changes to society. However, such an approach rarely plays out in reality.

Right-wing or conservative governments prioritize individual freedom over government intervention in society. For example, they tend to believe that a free market is critical to economic efficiency. Conservatives believe that excessive government regulation can stifle innovation and competitiveness. These governments focus on identifying and preserving things that are good about the present society. In turn, they often support smaller and more incremental changes rather than aggressive policies that could upend systems and invite unrest. But once again, the real world is complex. Many right-wing governments—such as those run by Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and Viktor Orbán in Hungary— have supported sweeping changes to society.

Those terms—left wing and right wing—date back to the French Revolution, when defenders of the monarchy sat to the right of the king and the radicals to the left. Back then, those on the left tended to favor change, and the right believed in preserving the status quo—or, indeed, returning to a previous political era.

While political ideologies describe the way governments think about their role in society, political parties are institutions—groups of people in a country that seek to advance certain social, economic, and foreign policy goals. In the United States, the Democratic Party is generally associated with left-wing positions and the Republican Party with right-wing ones. But left wing and right wing are relative terms and mean different things in different places (and, indeed, have meant different things at different times). Although the Democratic Party is the United States’ more liberal party, its positions have traditionally been more conservative when compared to liberal parties in Europe and Latin America. Liberal leaders on those continents tend to advocate for greater government involvement to achieve social equality than their American counterparts.

Governments are dynamic

Governments are complex and can be described in several dimensions. Describing a country as just “democratic” or “socialist” doesn’t tell the full story. Norway, for example, is a democracy falling somewhere between capitalism and socialism. And China, often described as an authoritarian government, implements a version of capitalism.

Those aren’t contradictions: governments perform various roles and are not all neatly packaged the same way. Understanding the choices governments make—how they structure their leadership, interact with the economy, and prioritize different social goals—is essential, as those decisions shape the lives of everyday citizens.