Modern History: Sub-Saharan Africa

For centuries, sub-Saharan Africa was home to prosperous empires that made groundbreaking advances in architecture, mathematics, and metalworking.

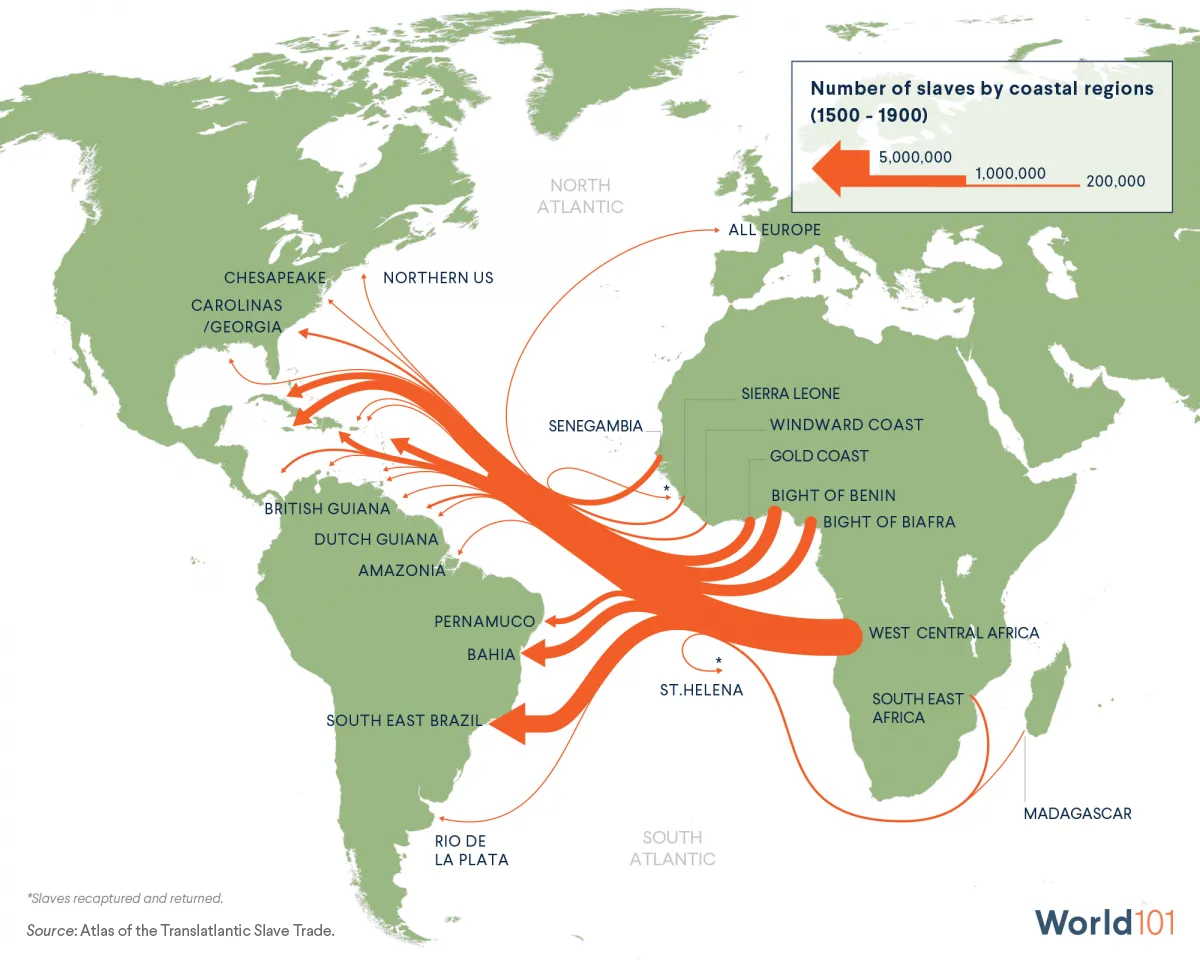

For centuries, sub-Saharan Africa was home to prosperous empires that made groundbreaking advances in architecture, mathematics, and metalworking. By the end of the fifteenth century, Europeans had begun arriving in the region, wanting to acquire resources such as gold, copper, and rubber. And slaves. Europeans enslaved and killed at least twenty million Africans between the sixteenth and mid-nineteenth century. When the slave trade abated by 1870, a new era in sub-Saharan Africa began: the age of colonialism. By 1914, European powers controlled almost 90 percent of the continent, often through the use of unmitigated violence. Twentieth-century sub-Saharan Africa also saw a wave of independence movements, sometimes bloody, sometimes peaceful, but almost always the result of a long and hard-fought battle with colonial powers.

Transatlantic Slave Trade Forces Millions to the Americas

For centuries, sub-Saharan Africa was home to prosperous empires, including the Aksumite Kingdom in modern-day Ethiopia and Sudan and the Ghana and Mali empires in West Africa. Europeans began arriving at the end of the fifteenth century, driven by the desire for resources, including labor. Slavery had been practiced all over the world, including in sub-Saharan Africa, for centuries. But the arrival of the Portuguese in the 1450s marked the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade during which at least twenty million Africans were enslaved and forced to migrate to the Caribbean and the Americas or killed in the process. The slave trade lasted into the early nineteenth century in many European countries and decades later in the United States.

Europeans Scramble for Resources in Africa

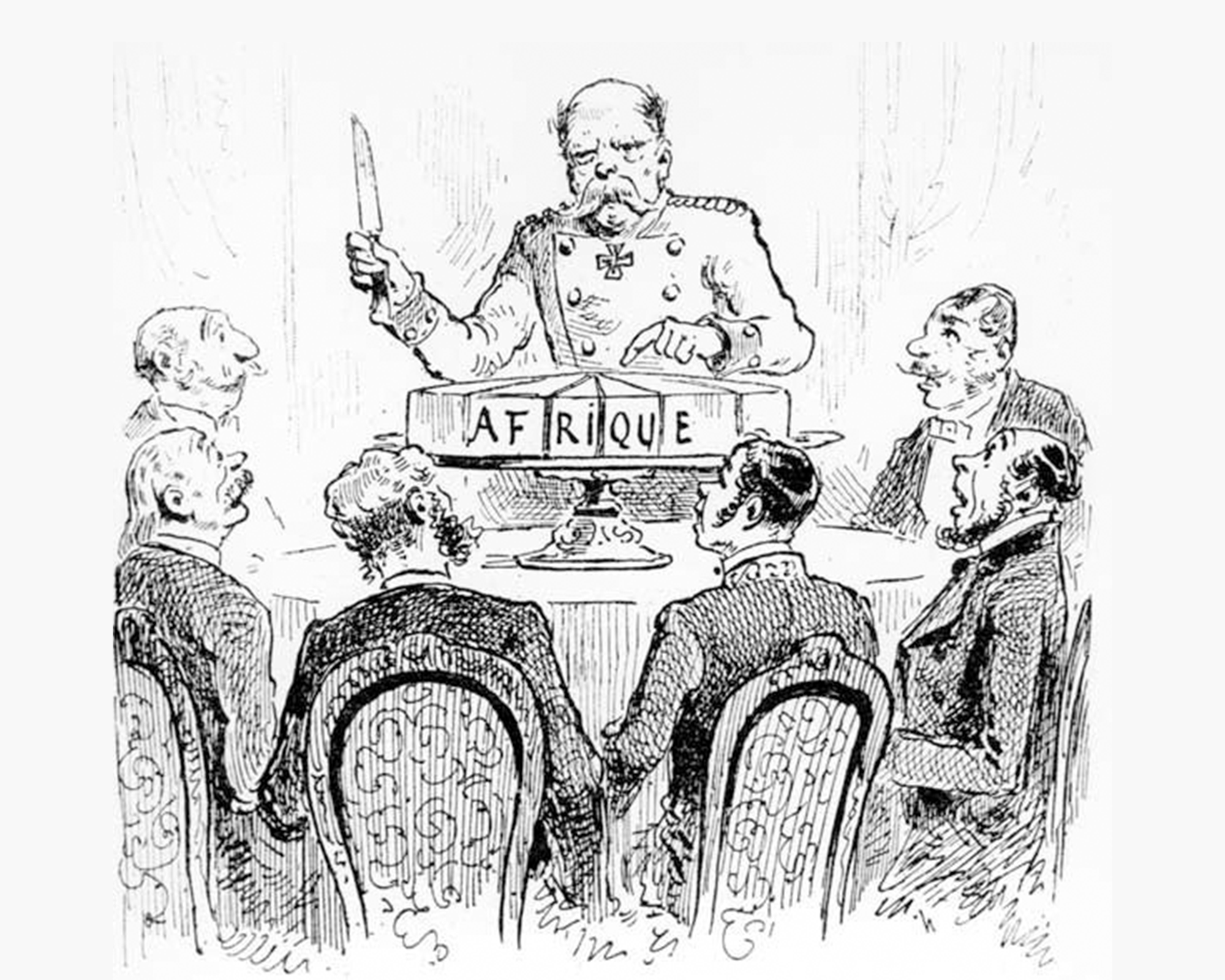

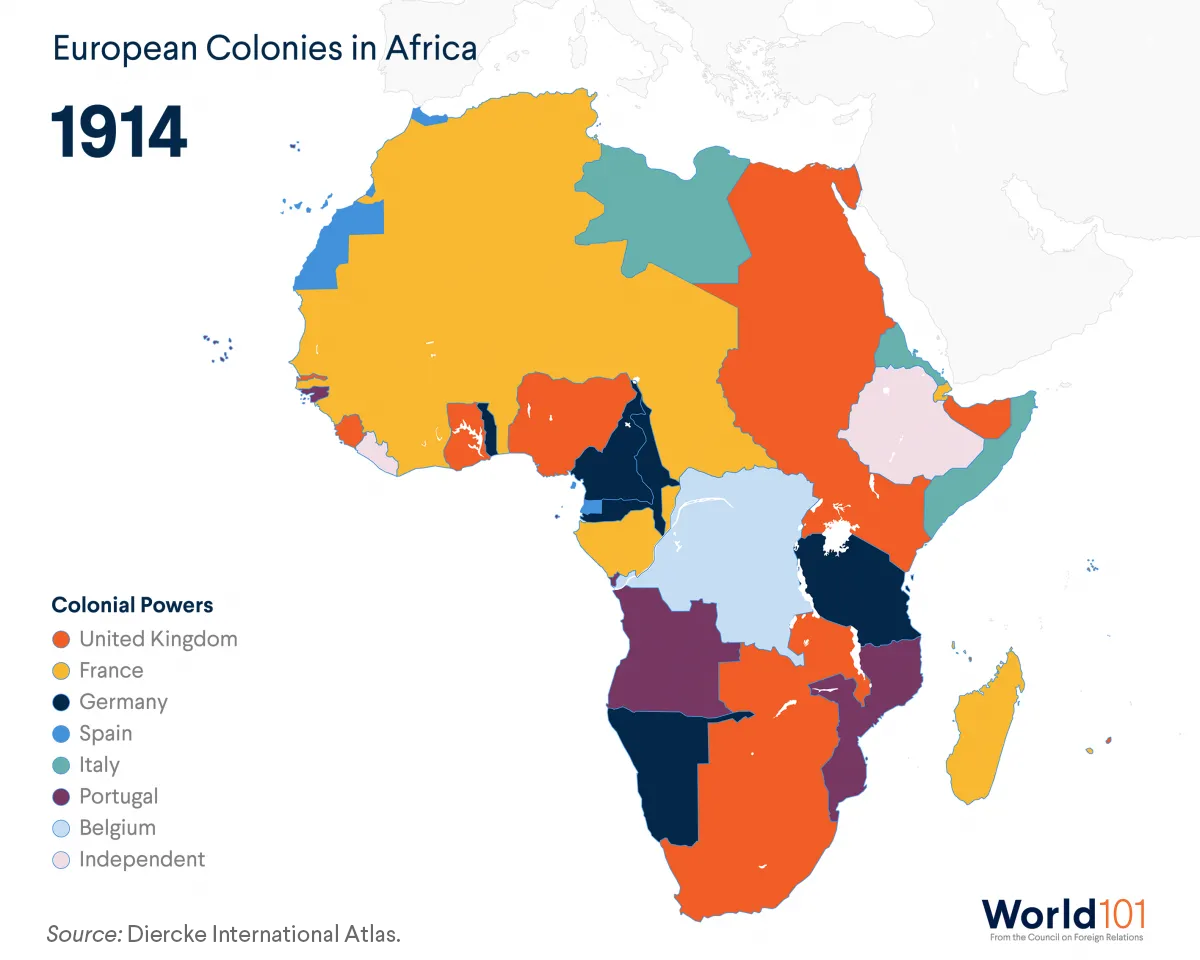

In the context of the Industrial Revolution, which was in full steam in Europe during the end of the 19th century, commodity and natural resource-rich Africa started to draw more and more of the world’s attention. In the late 1800s, representatives from fourteen countries met in Berlin to discuss how to divvy up their competing claims on Africa and its resources. Motivated by their desire to avoid a power struggle amongst themselves, representatives at the Berlin Conference drew colonial boundaries in Africa and decided matters ranging from trade rights to control over major rivers without a single African representative present. Although many Africans resisted the ensuing colonization of their region, Europeans moved quickly to exploit existing political divisions among the region’s kingdoms and leveraged a distinct advantage: guns. By 1914, European powers controlled almost 90 percent of the continent.

Colonialism Changes Course of African History

The colonial era upended life in Africa. Borders, forms of government, religions, and languages changed radically as colonial powers moved into the region, changes that would have long-term effects for sub-Saharan Africa. European powers were drawn to Africa for similar reasons: a desire for raw materials and new markets, the political cache of expanding their empires, and a desire to spread Christianity. But not all European powers ruled their African colonies in the same way. Some sent Europeans to run colonial governments and others promoted locals loyal to European administrations. Some employed extreme violence, most notably in the Congo where Belgian King Leopold II oversaw the murder of at least ten million Africans. Most colonial powers also relied on a principle called divide and rule, a strategy based on taking advantage of existing rivalries in order to maintain control. The legacy of this strategy is still evident today as the region continues to struggle with internal conflict and civil wars.

Ethiopian Resistance to Colonialism: A Model for Independence

Europeans were not universally successful in colonizing Africa. During the Scramble for Africa, Menelik II, the emperor of Ethiopia, fought off Italian invaders and their Eritrean allies in 1896. The subsequent emperor, Haile Selassie, also went on to form a sizable African empire of his own through several military campaigns. This anticolonial victory not only kept Ethiopia independent, but it also served as a powerful symbol of African resistance in the region, laying the groundwork for independence movements in the decades to come.

Post-World War II Africa Sees Wave of Decolonization

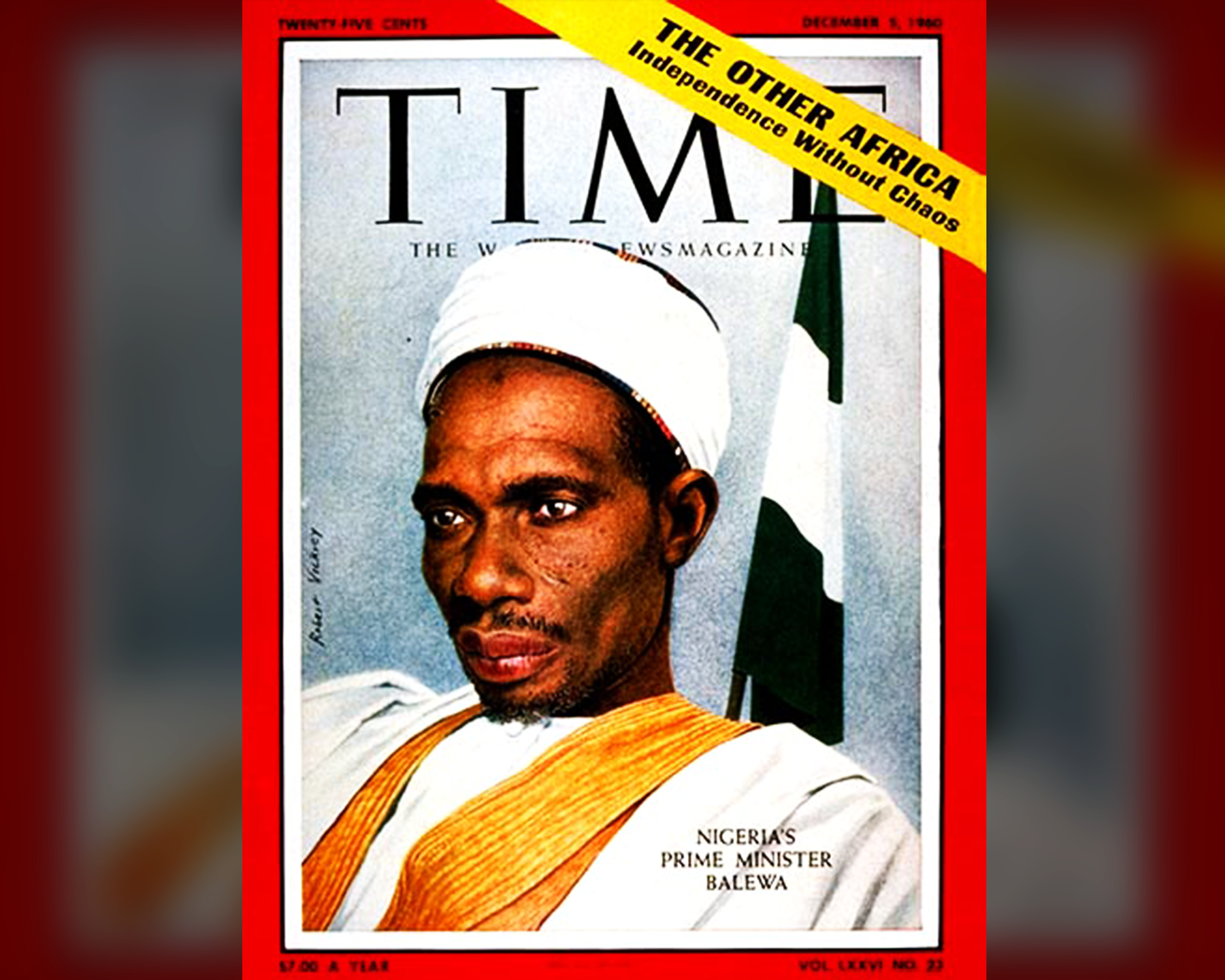

World War II upended the relationships European countries had with their colonies. During the war, many Africans fought for the Allies and were promised independence in return. When these promises didn’t materialize, anti-colonial movements gained steam across the region just as former colonial powers like the United Kingdom and France emerged from the war significantly weakened. New international bodies like the United Nations, founded in 1945, put forth principles like universal human rights and self-determination, which states that countries have a right to govern themselves. As these ideas mixed with the nationalist, anti-colonial sentiments already brewing in the region, a wave of independence movements swept across sub-Saharan Africa. In 1960 alone, seventeen African countries declared independence and joined the United Nations.

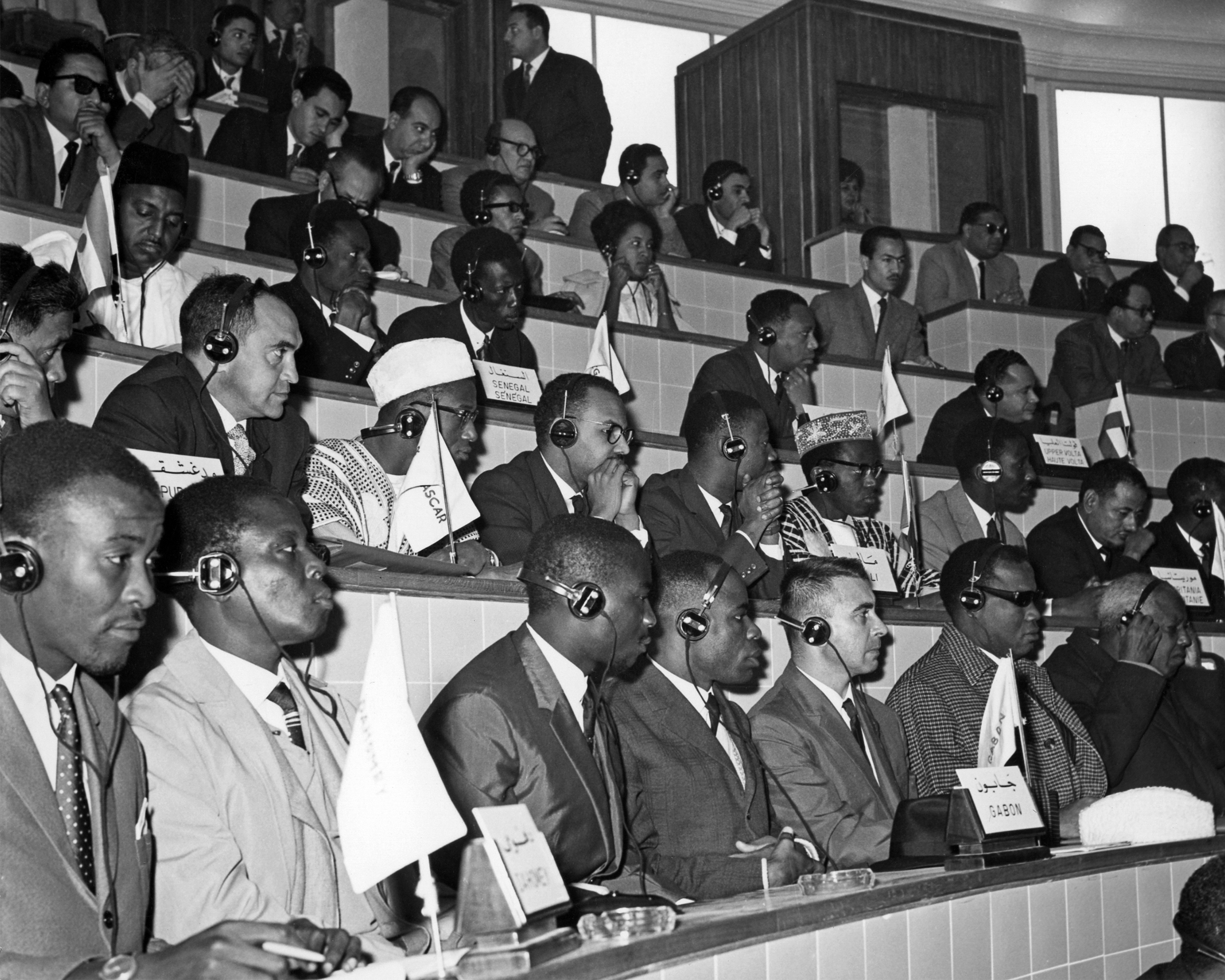

Pan-Africanism Inspires Organization of African Unity

Pan-Africanism is an ideology, over two hundred years old, that Africans both in and outside Africa share a common history and future, no matter where they live. During colonization, Black intellectuals across the United States, the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa called for solidarity and unity, on the belief that Africans could liberate themselves only by helping one another internationally. Spanning religious, cultural, and political forms, Pan-Africanism and its anti-colonial and pro-sovereignty ideas served as the foundations of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). Founded in 1963 by the thirty-two independent African nations of the time, OAU aimed to eradicate colonialism from the continent and promote international cooperation. The organization’s legacy lives on in the form of the African Union, a truly Pan-African organization that counts every African country as a member.

Cold War Proxy Wars Derail Independence

Independence brought radical new opportunities. Several post-independence leaders like Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara, Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere fought for a self-sufficient Africa in the Organization for African Unity and in their home countries. Other influential leaders, like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, supported a strong interpretation of the Pan-African movement by calling for a United States of Africa. But this new era of independence came just as the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies started heating up. Throughout the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union tried to expand their influence in the region by providing military and economic aid to governments supportive of their respective worldview. In some cases, these world powers supported interventions or were involved in proxy wars in newly independent African countries to ensure that governments friendly to their agenda remained in power.

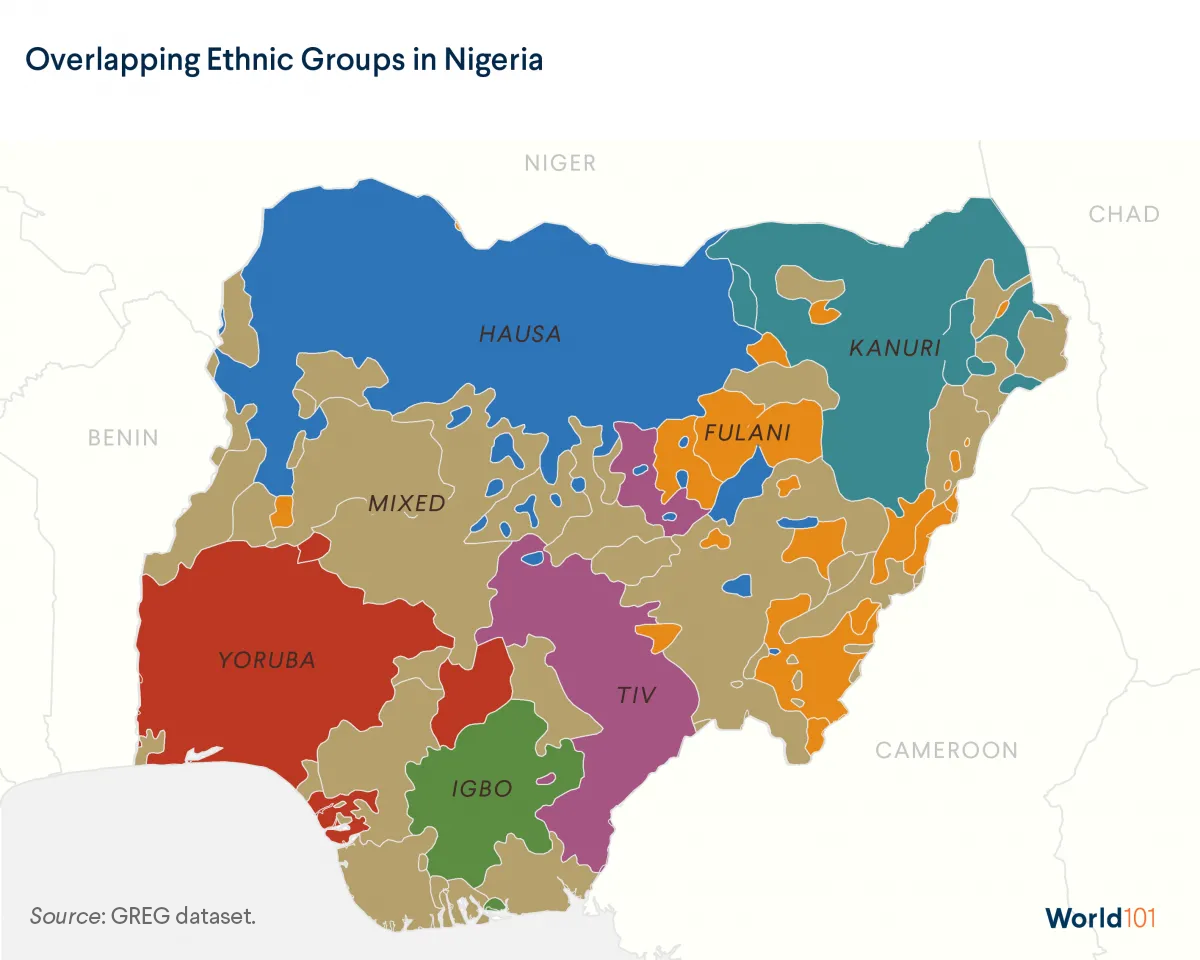

Legacy of Colonial Borders Causes Civil Conflict

Many of sub-Saharan Africa’s borders date back to colonial times, when boundaries were drawn without considering the people who would end up living on either side. After World War II, as countries gained independence, ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups within national borders started fighting for control. In 1964, many African governments formally agreed to maintain colonial borders in an effort to promote stability in the region. But this effort often failed. Just three years after this agreement, a bloody civil war broke out in Nigeria when an ethnic minority tried to secede and form the Republic of Biafra. Although the war ended in two and a half years with the surrender of Biafran forces, Nigeria has lived in uneasy peace ever since. Separatists in other countries were successful. In Ethiopia, separatists won independence after a thirty-year war, resulting in the new east African nation of Eritrea in 1993. A 2011 peaceful referendum in Sudan resulted in the formation of another nation, South Sudan, but civil war erupted in the world’s youngest country just two years later. These new nations, and the conflicts within and between them, show that the map of sub-Saharan Africa is still in flux.

South Africa’s Struggle Under Apartheid

In 1948, descendants of Dutch settlers known as Afrikaners came to power in South Africa on a platform of apartheid, the Afrikaans word for apartness. Under apartheid, everyone in the country was assigned to a racial group. Black South Africans could not vote, move freely throughout the country, live where they wanted, or work most jobs. Black resistance and global scrutiny of apartheid intensified during the 1970s, and by the late 1980s, South Africa was disrupted by internal boycotts and international divestment. After spending twenty-seven years in jail for protesting apartheid, Nelson Mandela became an international symbol of freedom as he led his country’s relatively peaceful transition to democracy as its first president in 1994.

Rwandan Genocide Shocks World

One of the world’s defining post–Cold War events occurred in 1994 in Rwanda, where the Hutu ethnic group perpetrated a genocide against the minority Tutsi ethnic group. The mass violence had roots in the colonial divisions made by the Germans and Belgians and decades of inequality between the ethnic groups. Hutus across the country embarked on a hundred-day campaign of violence, which killed nearly one million Tutsis and one hundred thousand Hutus. In the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide, many countries argued that the violence could have been stopped; since then, new international norms regarding humanitarian interventions to stop genocide have taken hold. Notably, the genocide spurred all UN member states to endorse the responsibility to protect (R2P) doctrine. R2P commits countries to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity; should they fail to do so, this responsibility—in theory—falls on other countries.