People and Society: East Asia & The Pacific

East Asia and the Pacific is the world’s largest region, accounting for nearly one-third of the global population.

East Asia and the Pacific is the world’s largest region, accounting for nearly one-third of the global population. With 1.4 billion people, China is the world’s most populous country and has more people than every other country in the region combined. The region’s countries are religiously diverse, with large numbers of Buddhists in Japan and Southeast Asia and the world’s largest Muslim population in Indonesia. In recent decades, the region’s economic success has dramatically improved living standards for millions: over the past half-century, average life expectancy has risen by an astounding thirty years and is now three years higher than the global average. From top-performing schools to well-equipped health-care systems, people in many East Asian countries are leading healthier and more productive lives. But factors like pollution, overcrowding, and an aging population across Northeast Asia threaten to reverse some of those trends.

Demographics Pose Economic Challenges for Northeast Asia

Across Northeast Asia, populations are rapidly aging—and, in Japan’s case, even shrinking—which poses major consequences for the region’s future economic prospects. An aging population usually means a loss of workers, a sluggish economy, and an increase in public spending to care for the elderly. Japan and South Korea will likely have the resources to care for their aging populations, but many observers warn that China—where one-third of the population will be over sixty by 2050 —will struggle to care for hundreds of millions of its elderly citizens. Experts attribute this demographic trend to low fertility rates and the legacy of China’s one-child policy, which limited the number of children most Chinese families were allowed to have. Although China ended the policy in 2015 after nearly forty years, its effects can still be felt. Based on current trends, China’s population will start to decline in 2027, foreshadowing a smaller labor supply and potential economic challenges.

Megacities Struggle to Accommodate Asia’s Urban Buildup

As Asian economies have grown, many Asian cities have modernized. Kuala Lumpur, Seoul, and Taipei, with their efficient public transit system and high-speed internet, are symbols of the region’s economic prosperity. But elsewhere, urban populations are growing too fast for cities to keep up. Megacities like Beijing and Bangkok, with populations of more than ten million people, face infrastructure issues such as clogged streets, inadequate waste management, and water scarcity. And in countries like Indonesia, where people are migrating to cities four times faster than in the United States, simply getting from point A to point B can be a struggle: in Jakarta, for example, it is not unusual for automobiles to sit in traffic for hours to travel just a few miles.

Pollution and Deforestation Show Environmental Cost of Development

This region has achieved immense growth, but it’s come at a cost to the environment. As the Chinese government built more factories and hundreds of millions of people moved from rural areas to cities, pollution skyrocketed. In 2005, China overtook the United States as the world’s biggest polluter, and by 2014, China emitted more greenhouse gases than 170 countries combined. Elsewhere in the region, Indonesia and Malaysia have exploited natural gas, petroleum, and palm oil to boost their exports. Palm oil is lucrative, because it is used in a wide range of consumer goods (e.g., cosmetics, cleaning products, and food products), but the need to increase production has led to massive deforestation, contributing to forest fires and worsening air quality across the region. Deforestation also means fewer trees to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as well as the release of carbon stored by razed trees, exacerbating climate change.

Health Miracle in East Asia Boosts Life Expectancy

The rapid economic growth that occurred in much of the region over the last fifty years allowed for vast improvements in public health. Average life expectancy across East Asia and the Pacific jumped from forty-eight years in 1960 to seventy-five years in 2016, partially due to advances in treatment for infectious diseases and access to those treatments. For example, Thailand, which struggled with managing HIV/AIDS in the past, now has a strong track record of treating people with HIV. However, as overall health has improved across the region, longer life spans and lifestyle changes mean the biggest health concerns have shifted from infectious to noncommunicable diseases like heart disease and stroke.

Technology Helps East Asia Control Spread of Coronavirus

Several countries in East Asia quickly controlled the spread of COVID-19 through early and extensive infection testing as well as innovative technological solutions. These measures have allowed governments to conduct contact tracing—the process of mapping the person-to-person transmission of the virus—which allows health officials to identify and quarantine potentially infected individuals before they endanger others. South Korea swiftly tested hundreds of thousands of its citizens—many at drive-through test sites—free of charge. Meanwhile, Singapore and Taiwan have used cell phone data and video surveillance to monitor the spread of the disease. These governments attribute much of their ability to implement effective and rapid responses to their recent experience dealing with other deadly strains of the coronavirus family; after fighting severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2015, many governments invested heavily in their health systems, especially in developing their testing capacities. Through such technologies as well as early and aggressive policy responses, many East Asian countries have experienced much lower infection and mortality rates from COVID-19 than the rest of the world.

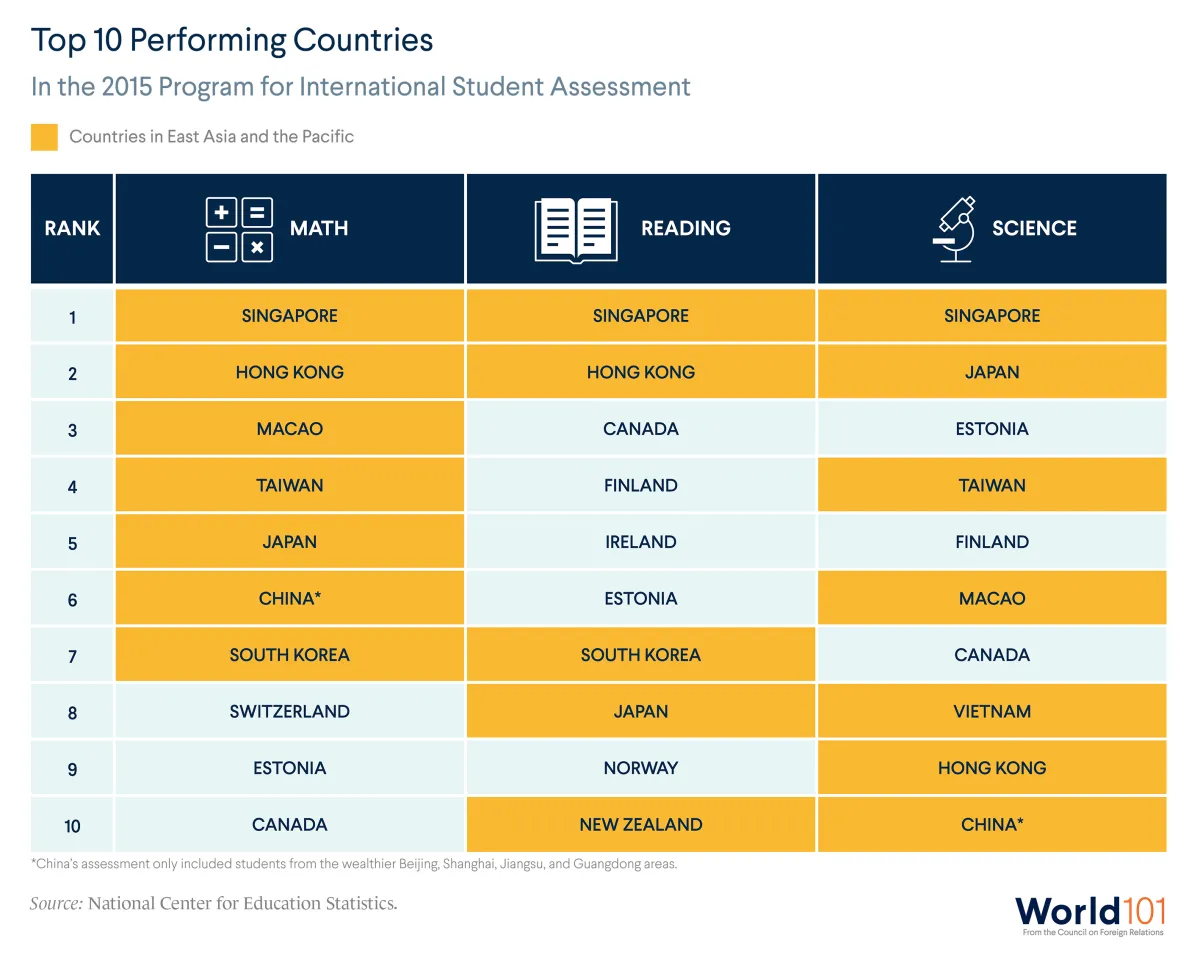

Region Home to World’s Top-Performing Students

In 1950, the average adult in East Asia had just over a year of schooling, less than half of the world average at that time. But today, most of the region’s more than 330 million school-aged children are in school. Equally impressive, this enrollment percentage has remained high even as the region’s population has more than doubled. The quality of education has risen as well, illustrated by the consistently high marks East Asian students receive on international exams. Many experts view education as being instrumental to the immense economic growth that parts of the region have experienced, noting that continued growth led to further education investment and vice versa. Some common strategies found across the region include prioritizing education in national budgets and higher salaries for teachers.

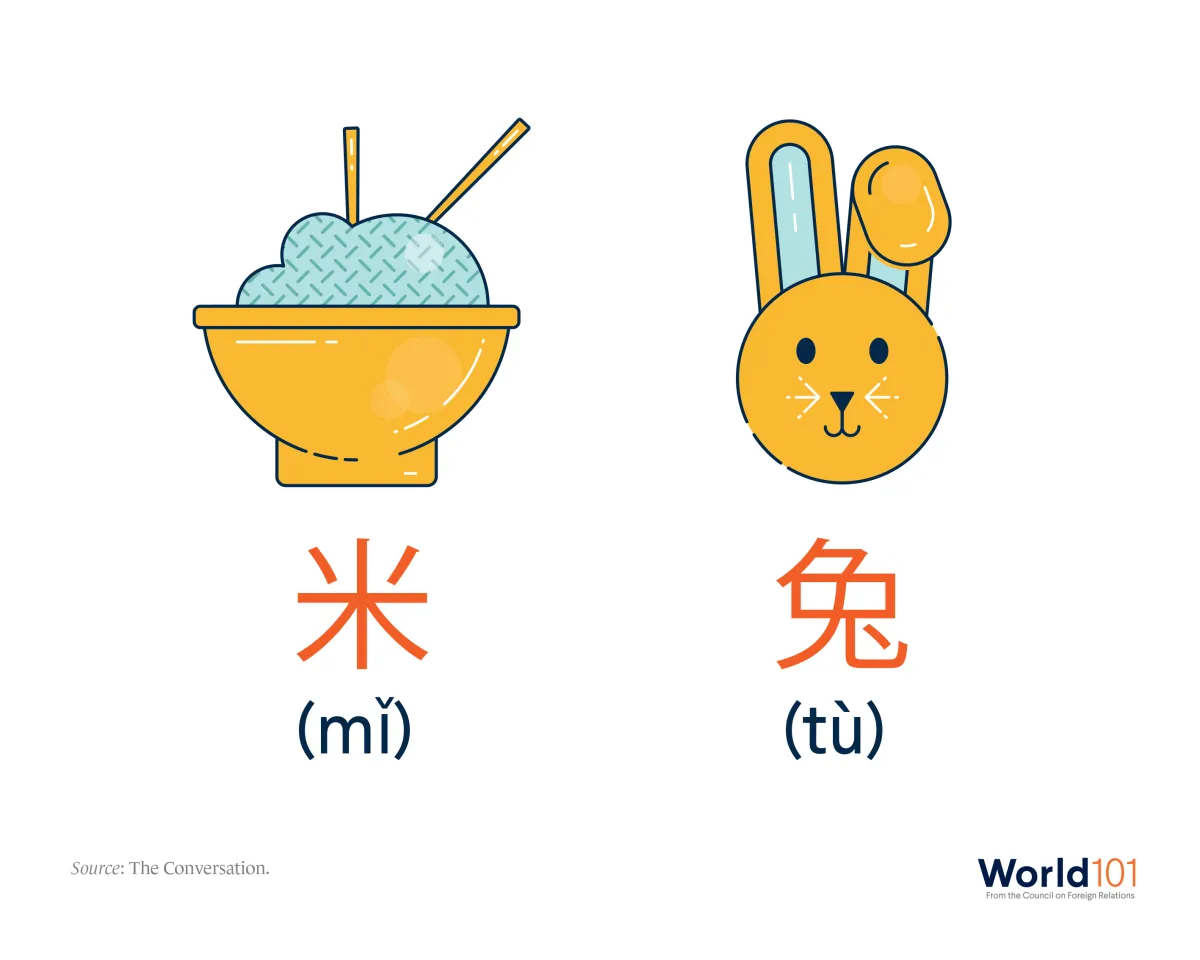

Rice Bunny Movement: Creative Ways to Fight Gender Discrimination

As in other parts of the region and the world, women in China face a gender wage gap, sexual harassment, and social discrimination. These issues have given rise to a feminist movement against sexual harassment and traditional gender roles. But almost all public protests in China are illegal, so feminist groups have had to get creative. When the #MeToo movement swept the United States in 2018, the Chinese government worried it would catch on in China and cause civil disobedience. The government immediately banned the hashtag on Chinese social media: any post with #MeToo would simply not show up. But feminists got around the censorship by using the emojis for rice and bunny instead—which are pronounced mi and tu in Chinese.

Language and Ethnicity Help Forge National Identity

East Asian countries are some of the least diverse places in the world: Japan is 98 percent ethnically Japanese, and both North and South Korea are 99 percent ethnically Korean. Even China, a country of more than one billion people, is over 91 percent Han Chinese. In East Asia, these ethnic similarities often translate into a sense of shared national identity, which can lead to robust democratic participation, but they can also encourage resistance to immigrants and opposition to other minorities, making it harder to address issues related to these countries’ aging populations. Southeast Asia, on the other hand, contains huge linguistic and ethnic diversity. For example, Papua New Guinea is the most linguistically diverse country in the world with more than 850 languages spoken by just 7.6 million people. And Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest country with over 260 million people, is a country of six thousand inhabited islands, hundreds of languages, five recognized religions, and dozens of ethnicities. This spectacular diversity can make it difficult for leaders to construct and maintain the same sense of national identity as in East Asian countries.

Little Room for Religion Under Atheist Chinese Communist Party

On paper, freedom of religion is constitutionally protected in China. But in practice, religious groups face persecution under the officially atheist Communist Party. The government has imprisoned thousands of followers of Christian groups and spiritual movements like Falun Gong, claiming that such groups are cults trying to overthrow the state. In Tibet, it’s illegal for Tibetan Buddhists to publicly praise or own a portrait of the Dalai Lama, their spiritual leader. Recently, the Chinese government as committed human rights abuses in the Muslim-majority Xinjiang Province. Since 2018, the government has detained approximately one million Muslims, mostly ethnic Uighurs, in camps, where they face violent persecution and are made to recite Communist Party slogans and renounce their religious beliefs. China claims these so-called reeducation camps are part of an anti-extremism campaign. But Uighur refugees claim that the government is trying to eradicate their culture and religion. The government has destroyed mosques across Xinjiang and has made it illegal to grow long beards, wear headscarves, or even fast during Ramadan.

Religion Is an Influential Force Across Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia has a rich and diverse religious history. Buddhism is the main religion in most Southeast Asian countries, Indonesia is the world’s largest Muslim country, and the Philippines is home to the world’s third largest Catholic population. Today, religion is an influential force across the region. Most men in Thailand and Myanmar temporarily serve as monks in Buddhist monasteries as young adults. In Brunei and parts of Malaysia and Indonesia, the government implements Islamic law, which criminalized adultery and insulting the Prophet Mohammed. Elsewhere, such as in Buddhist-majority Myanmar, discriminatory religious laws target the country’s Rohingya Muslims and other ethnic minorities. With all this diversity, there are ongoing conflicts involving Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim minorities in many of the region’s countries.