U.S. Foreign Policy: Middle East and North Africa

Since World War II, three main interests—ensuring the free flow of oil from the Gulf, guaranteeing the survival and security of Israel, and limiting the influence of the former Soviet Union—have driven U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East.

Since World War II, three main interests—ensuring the free flow of oil from the Gulf, guaranteeing the survival and security of Israel, and limiting the influence of the former Soviet Union—have driven U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East. These goals have pushed the United States to mediate peace, like when it negotiated the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel in 1978, and to intervene militarily, such as when it led an international coalition to beat back Saddam Hussein’s invading Iraqi forces from Kuwait in 1991. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 9/11 terrorist attacks that killed 2,977 people, and Iraq and Iran’s efforts to acquire nuclear weapons, the United States’ foreign policy priorities grew to incorporate countering terrorism and nuclear proliferation. The United States now promotes economic growth via billions of dollars in annual foreign aid and projects its military power throughout the region with military bases in more than half a dozen countries, an offshore naval presence in the Gulf, and military assistance and arms sales to its partners, notably Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

Oil Draws United States to Middle East

The United States produced a resounding 60 percent of the world’s oil supply at the start of World War II. This energy dominance allowed the United States to fuel the militaries of its allies (including Britain and France) while its enemies (Germany and Japan) struggled to do the same. But as World War II neared its end, U.S. energy experts feared that the country’s oil fields would run out in the coming years. Securing new oil sources abroad thus became a national security priority. As a result, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began to pursue closer relations with Saudi King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud, whose country had recently discovered its own vast oil reserves. The two leaders met in February 1945, marking an important start to a bilateral relationship that continues to this day.

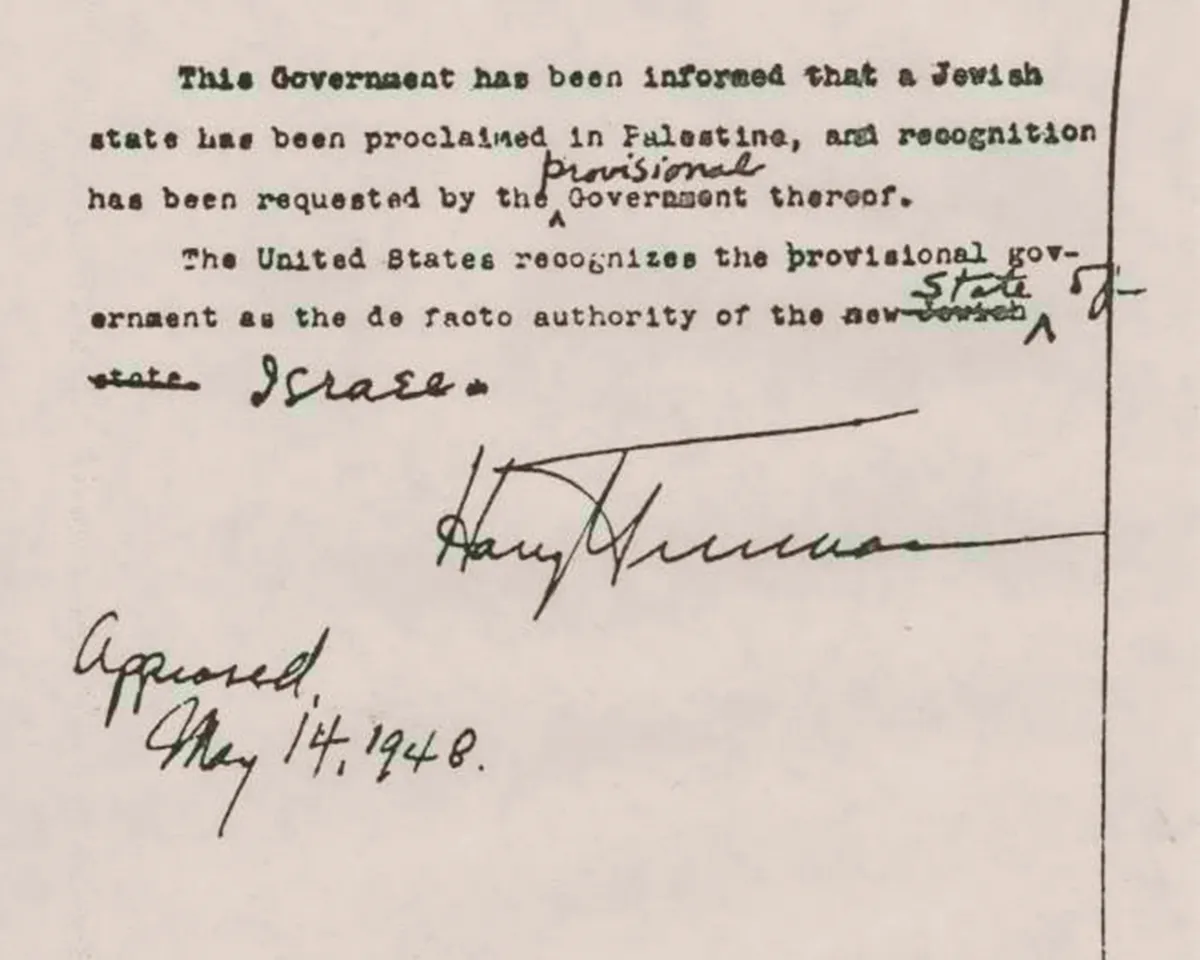

United States Recognizes Israel, Alienates Arab Neighbors

The United States’ relationship with Israel—its closest partner in the Middle East—dates back to May 14, 1948. Just eleven minutes after Israel declared its independence, President Harry S. Truman officially recognized the new country. Morally, he felt an obligation to provide European Jews with a haven and a homeland following the atrocities of the Holocaust. Politically, he saw an opportunity to secure Jewish votes in the United States in the lead-up to the 1948 presidential election by recognizing Israel. Strategically, he believed backing this young democracy would prevent the Soviet Union and communism from gaining a new foothold in the region in the early years of the Cold War. President Truman’s decision, however, alienated the United States from the region’s Arab countries, which refused to recognize Israel as a legitimate country.

Suez Crisis Becomes Flashpoint in Cold War

During the Cold War, U.S. officials were eager for anything that might erode the world’s opinion of the Soviet Union, and they got just that in 1956 when Hungarian citizens overthrew their communist government. The Soviet Union responded, sending its military in to brutally crush the revolution. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower pointed to the bloodshed in Hungary as a prime example of Soviet repression. But, at the same time, an event in the Middle East undermined the United States’ Cold War messaging. Britain, France, and Israel unexpectedly invaded Egypt in a bid to retake the country’s strategic Suez Canal. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was furious that the invasion distracted the world’s attention from the anti-communist uprising in Hungary and threatened to push the Arab world even closer to the Soviet Union, so he compelled Britain and France to withdraw from Egypt. Shortly thereafter, President Eisenhower pledged the United States would provide financial and military support to any Middle Eastern country that felt threatened by outside aggression in order to ensure that the Soviet Union could not expand its influence in the region.

Glimmer of Peace Between Israel and Arab World

In the 1970s, Israel was just three decades old and a pariah in the Arab world. It had already fought three wars against its Arab neighbors, all of whom rejected Israel’s right to exist. Following the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger brokered a series of agreements, laying the foundations to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict and remove the tension between America’s interests in Israel’s survival and good relations with Arab oil producers (notably Saudi Arabia). In 1978, President Jimmy Carter built on these foundations to promote a breakthrough to peace between Israel and Egypt. While Egypt deeply distrusted Israel, it saw a peace deal as an opportunity to regain the territory it lost in the 1967 Six Day War, improve relations with the United States, and boost its struggling economy. President Carter invited both countries’ leaders to the United States for two weeks of secret negotiations that culminated in the Camp David Accords—a landmark peace treaty between the two formerly bitter rivals. This agreement removed the largest and most militarily powerful Arab country from the conflict with Israel. For decades, U.S. administrations have sought to replicate the success at Camp David, but to date only four other Arab countries—Bahrain, Jordan, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates—have established formal diplomatic relations with Israel.

Iran: From Ally to Enemy

Today, Iran is the United States’ fiercest rival in the Middle East. But for most of the twentieth century, the two were close partners with common interests in regional security and oil. In 1953, the CIA even backed a coup in Iran that overthrew a democratically elected prime minister in order to keep the shah—a U.S. ally—in power. Most Iranians, however, saw the shah as a corrupt American puppet whose secret police tortured and imprisoned dissidents. This frustration culminated in the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which toppled the shah and brought a fiercely anti-Western government to power—one led by Ruhollah Khomeini, a formerly exiled cleric who opposed American interests in Iran and around the region. Soon after the revolution, Iranian university students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking American staff hostage for 444 days. The crisis resulted not only in American sanctions on Iran but also the severing of diplomatic relations, which remain suspended more than four decades later.

United States Leads International Coalition to Liberate Kuwait

In 1990, Iraq invaded and annexed its smaller southern neighbor Kuwait, prompting immediate international outrage. The United Nations demanded that Iraq withdraw. When it refused, the United States led an international coalition of thirty-eight countries—the largest military alliance since World War II—to liberate Kuwait. U.S. President George H.W. Bush worried that a lack of international response could encourage Iraqi President Saddam Hussein to invade Saudi Arabia next, potentially giving an unpredictable dictator control over much of the world’s oil supply. President Bush also believed Iraq posed a risk to Israel’s security, given its threats to use chemical weapons against the Jewish country. Additionally, he acted to defend the principle of sovereignty—that no country’s territory could be taken by force. Ultimately, more than five hundred thousand American troops fought in the Gulf War, leading to a swift defeat of Iraqi forces. But after liberating Kuwait, coalition forces decided not to push into Iraq’s capital, Baghdad, to depose its dictator. It would be another decade before U.S. troops returned to undertake that mission.

9/11 Attacks Redefine U.S. Counterterrorism Strategy

On September 11, 2001, militants from the terrorist group al-Qaeda hijacked four planes and used them as weapons to kill 2,977 people. In response, the U.S. Congress passed the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), which gave the president sweeping power to pursue the attacks’ perpetrators and their supporters. The AUMF, however, did not define a specific target or establish an end date for these broad new powers. As a result, this sixty-word authorization has been used to justify some of the United States’ most significant military and counterterrorism operations in the region and around the world, including the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, air strikes against al-Qaeda affiliates in Somalia and Yemen, and even extensive surveillance of American citizens. Today, nearly two decades later, the AUMF is still being used to justify military action in Iraq and Syria against the Islamic State, a terrorist group that didn’t even exist at the time of the 9/11 attacks.

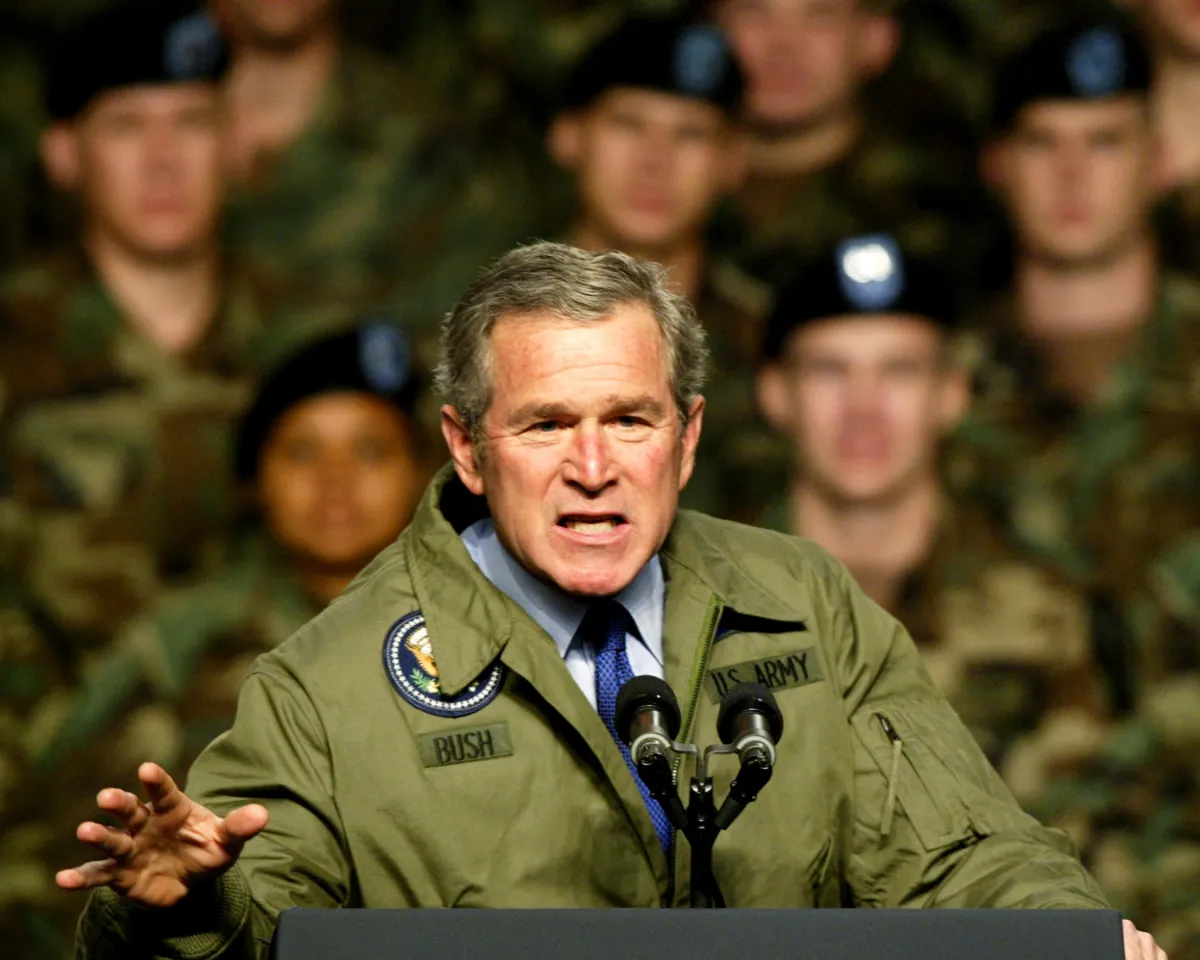

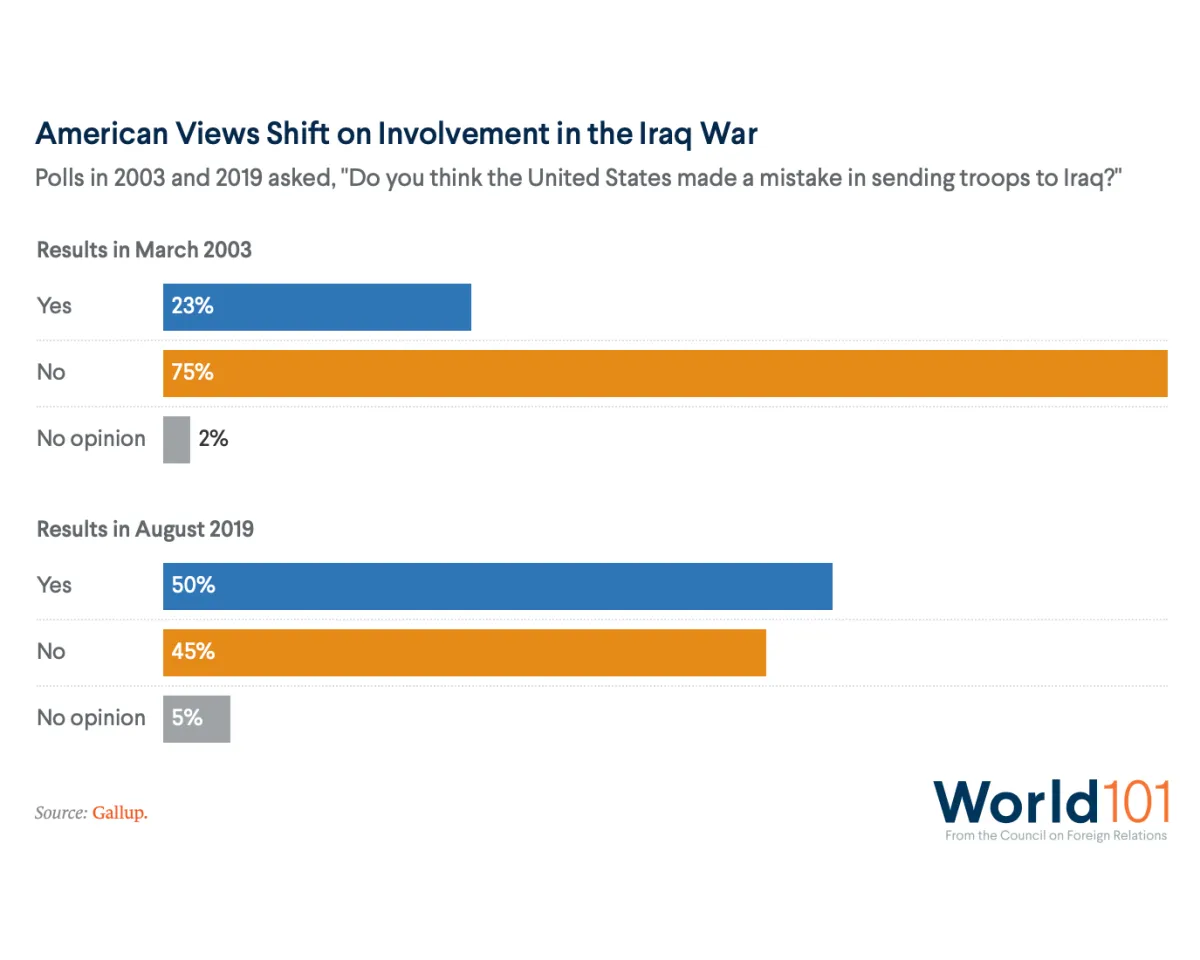

Tremendous Costs of U.S. Invasion of Iraq

In 2003, President George W. Bush dispatched a U.S.-led coalition to Iraq for a controversial regime-change operation that would have long-lasting consequences for the United States’ role in the Middle East. President Bush claimed the invasion would overthrow Saddam Hussein’s repressive regime, which allegedly harbored terrorists and possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). Other administration officials argued that removing Saddam could launch a larger wave of democratization across the region. These justifications for intervention were brought into question when, after Saddam’s death, inspectors found no evidence of WMDs, and Iraq descended into chaos. What is clear, however, is that the United States paid dearly for its invasion—nearly 4,500 U.S. soldiers died in the Iraq War, which cost American taxpayers almost $1 trillion. What’s more, countries throughout the region, as well as close American allies, criticized the United States for starting a conflict that unraveled a country and led to hundreds of thousands of Iraqi deaths. Successive administrations have sought to avoid similar regime change–focused interventions. Nevertheless, the United States still maintains around five thousand troops in Iraq, a country that has suffered through civil war, extremist insurgencies, and political upheaval.

Humanitarian Intervention Precipitates Civil War in Libya

In 2011, millions of people across the Middle East rose up to demand political, economic, and social reforms from their highly repressive governments in a wave of protests called the Arab Spring. In Libya, the country’s dictator—Muammar al-Qaddafi—threatened to kill protesters en masse. This situation left President Barack Obama with a difficult decision. His administration could remove Qaddafi militarily, but would risk embroiling American troops in yet another Middle Eastern conflict so soon after the invasion of Iraq. Alternatively, he could do nothing, which could have allowed a massacre to unfold. Instead, he opted to gather international support for a limited, humanitarian intervention, strictly to protect vulnerable Libyan civilians. This intervention, however, changed the course of Libya’s war, ultimately allowing rebel forces to capture and kill Qaddafi. The fact that this once-limited humanitarian intervention evolved into effectively a regime-change operation infuriated Russia and China and alienated international support for future humanitarian interventions, including in Syria. Furthermore, with the United States and other countries unwilling to make a lasting commitment to rebuild Libya, the country quickly returned to civil war, demonstrating that intervention—even limited and with humanitarian intentions—can bring destabilizing consequences. President Obama called the failure to plan for Libya’s transition the “worst mistake” of his presidency.

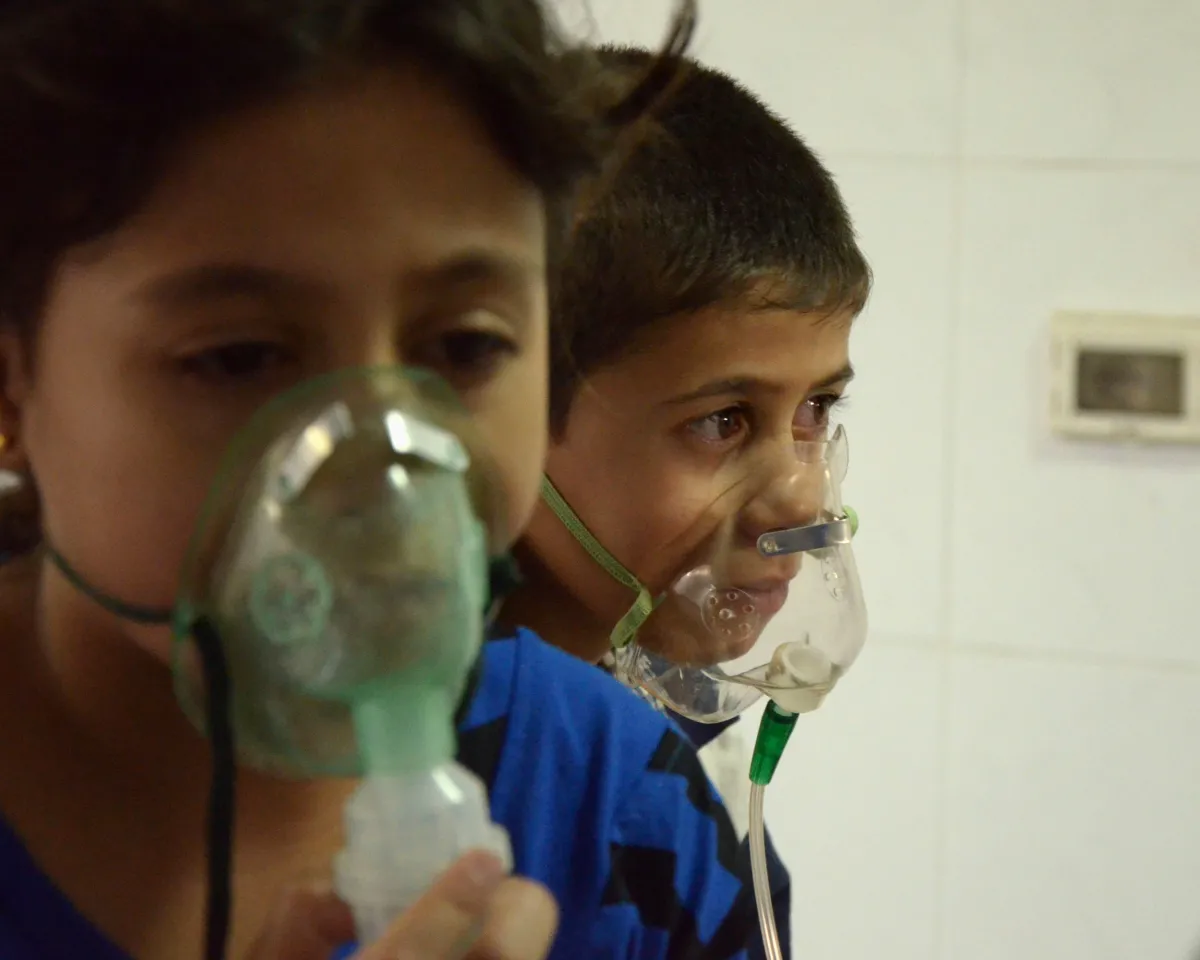

Syrian Civil War Spirals as United States Refuses to Intervene

After the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the 2011 humanitarian intervention in Libya both resulted in destabilization and civil war, the United States resolved to avoid further military overreach. So when peaceful protests devolved into all-out violence in Syria in 2011, President Barack Obama supplied limited weapons and training to moderate rebels who opposed Syria’s oppressive ruler Bashar al-Assad, but he stopped far short of providing support that could meaningfully alter the outcome of the civil war. He did, however, state that the use of chemical weapons by Assad would be seen as crossing a “red line” that could draw the United States directly into the conflict. But when Assad gassed hundreds of civilians just outside the Syrian capital in 2013, President Obama refused to intervene, a decision that empowered the Syrian regime and undermined U.S. credibility among its friends and allies. Assad would go on to kill hundreds of thousands of civilians in a war that has displaced more than half of the country’s pre-war population, proving that U.S. inaction in the region can enable humanitarian crises just as much as poorly executed American military interventions.

United States Shifts Tactics in Confronting Iranian Nuclear Threat

The United States has long opposed Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons given the threat such a bomb poses to Israel—the United States’ closest ally in the Middle East—and its potential to spur a nuclear arms race in this highly volatile region. In 2015, Iran was only months away from developing this weapon. So, the United States, along with five other countries, negotiated and signed a landmark deal with Iran known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2015, which lifted international sanctions in exchange for a fifteen-year limit on Iran’s nuclear program. Opponents of the deal, however, claimed it did not do enough to ensure that Iran would never acquire nuclear weapons and that it failed to address Iran’s sponsorship of terrorism in the region as well as its ballistic missile program. President Donald J. Trump withdrew the United States from the JCPOA in 2018, reinstating all U.S. sanctions on Iran. In response, Iran has once again begun producing enriched uranium, which is needed to create an atomic bomb.

U.S.-Saudi Partnership Grows Despite Criticism

For decades, Saudi Arabia has been one of the United States’ closest partners in the Middle East. Originally focused on oil and security cooperation, today the two countries partner to counter terrorism and Iran’s expanding influence in the region. Additionally, Saudi Arabia is the largest importer of American-made weapons and has invested billions in American companies. However, this partnership has faced challenges in recent years. The majority of the 9/11 hijackers were Saudi citizens, casting doubts on the kingdom’s commitment to counterterrorism. The Saudi government also continues to wage a highly controversial war in Yemen, where it has repeatedly bombed civilians, generating the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Most recently, in October 2018, Saudi agents assassinated and dismembered Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi at their consulate in Istanbul, a killing that U.S. intelligence directly links to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. This brazen murder has led American politicians and human rights advocates alike to demand a reexamination of the U.S.-Saudi partnership.

U.S. Interests, Influence Shift Away From Middle East

For more than half a century, the United States has been the dominant outside actor in the Middle East. It has used this position to advance its foreign policy priorities—namely, defending Israel and ensuring the free flow of oil. But today the United States’ interests—and influence—in the Middle East are shifting. Israel is no longer a vulnerable country but rather a military heavyweight that is strengthening relations with former rivals like Saudi Arabia and Egypt. The United States no longer relies on Middle Eastern oil but rather is a net energy exporter through its recent boom in oil and gas production. Meanwhile, the American people are war-weary following the disastrous occupation of Iraq, and new foreign policy challenges, like the rising influence of China, demand American attention elsewhere. While the United States remains committed to supporting Israel, combating terrorism, and preventing Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon, it has also ceded influence in the region. But with tensions escalating with Iran, one sudden misstep could draw the United States back into yet another costly conflict in the Middle East.