Modern History: East Asia & The Pacific

East Asia is home to some of the world’s oldest civilizations.

East Asia is home to some of the world’s oldest civilizations. Chinese history stretches back more than four thousand years, and its early empires—some of the wealthiest in history—invented paper, movable type (in printing), gunpowder, and the compass. Korea and Japan, similarly, trace their histories back to dynasties across thousands of years that shaped the language and culture of their modern-day countries. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Americans, British, Dutch, and French had colonized much of Southeast Asia. Japan took Europe’s lead, creating colonies of its own in Korea, Taiwan, and China, and becoming an imperial power by the twentieth century, eventually allying itself with Nazi Germany during World War II. After the war, Japanese and European colonies became independent—but in the face of the Cold War, their challenges were far from over.

Japanese Empire Rivals European Colonial Powers

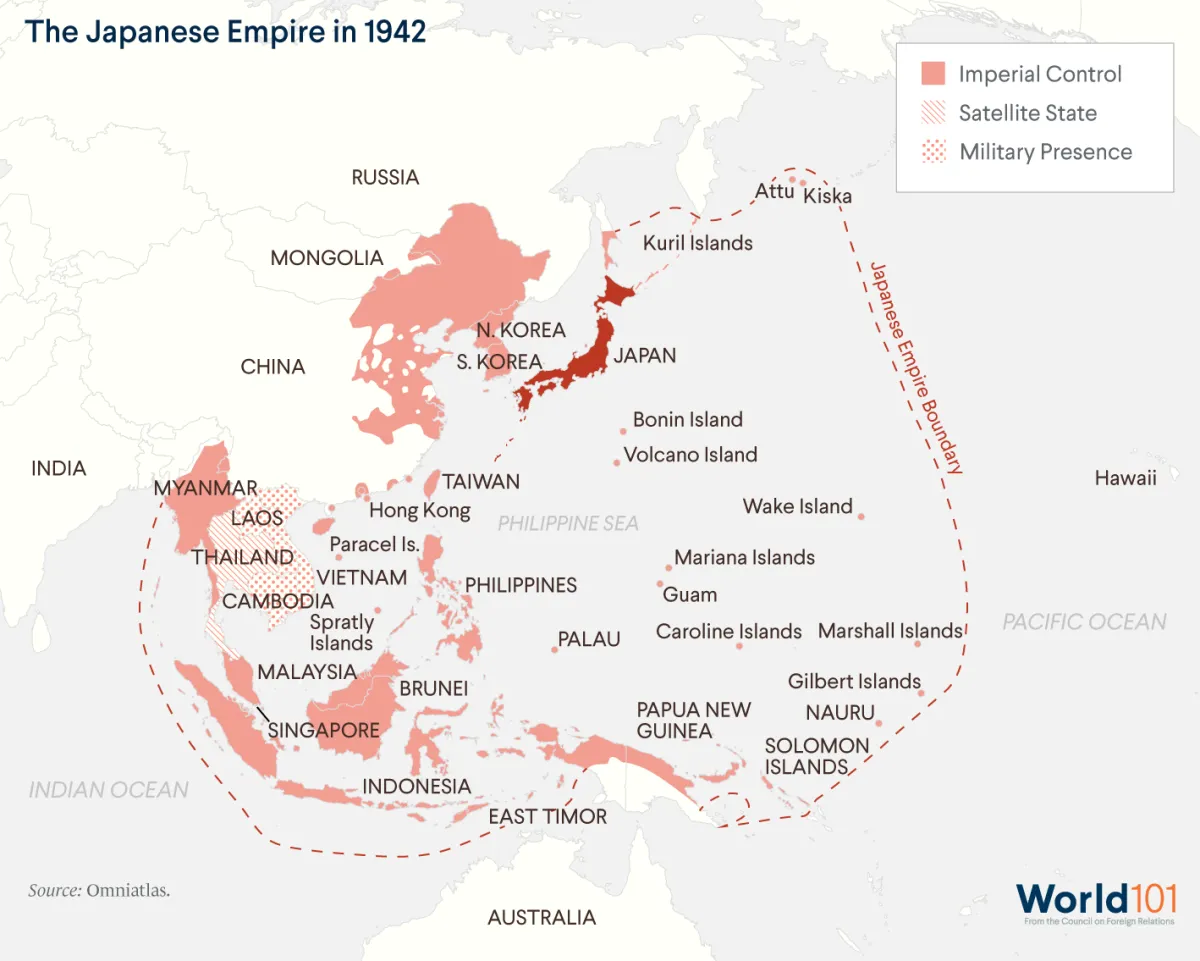

For hundreds of years, the Americans, British, Dutch, French, and Russians colonized East Asia, often in pursuit of natural resources, new trading outposts, and ever-expanding empires. But such colonialism came at great cost to local communities. France heavily taxed its colonies in modern-day Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam and exploited local resources like opium, rice, salt, and tea. The Dutch, meanwhile, controlled Indonesia and enriched their empire through the lucrative spice trade. But one of the most oppressive colonizers came from within the region: Japan. At its peak, in 1942, the Japanese Empire ruled over two hundred million people across thirteen modern-day countries, and it did so through extraordinary violence. Japan committed atrocities all over its empire, conscripting over one million Koreans as slave labor and forcing hundreds of thousands of girls and women from its colonies into sexual slavery. In one of the region’s darkest chapters known as the Nanjing Massacre, between 1937 and 1938 Japanese soldiers killed up to two hundred thousand people and raped tens of thousands of women in China. This episode and Japan’s other wartime actions continue to complicate bilateral relations between Japan and its neighbors China and South Korea to this day.

From Empire to Democracy: Japan’s Postwar Reconstruction

In 1940, Japan allied with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, forming the tripartite Axis powers of World War II. Japan entered the war hoping to expand its empire across Asia. Instead, its defeat by Allied forces (including the United States, Great Britain, and Russia) ended the country’s eighty-year empire. Upon Japan’s unconditional surrender in 1945, the United States occupied the country with more than two hundred thousand troops. And while these troops helped keep peace, U.S. political advisors worked with Japanese leaders to overhaul the government structure. They wrote a new constitution, which instituted democratic reforms, limited the role of the emperor, and disarmed the country’s military. Today, Japan has a thriving democracy and a flourishing economy. After reconstruction, Japan became the world’s second largest economy (behind the United States) and is still the third largest. Nevertheless, its wartime actions continue to strain diplomatic and trade relations with its neighbors. Most notably, Japan and South Korea entered a trade war in 2019 largely over disagreement on reparations for Koreans formerly forced into labor, including the thousands of so-called comfort women whom the Japanese Empire had forced into sexual slavery.

Civil War Sets Stage for Modern China and Taiwan

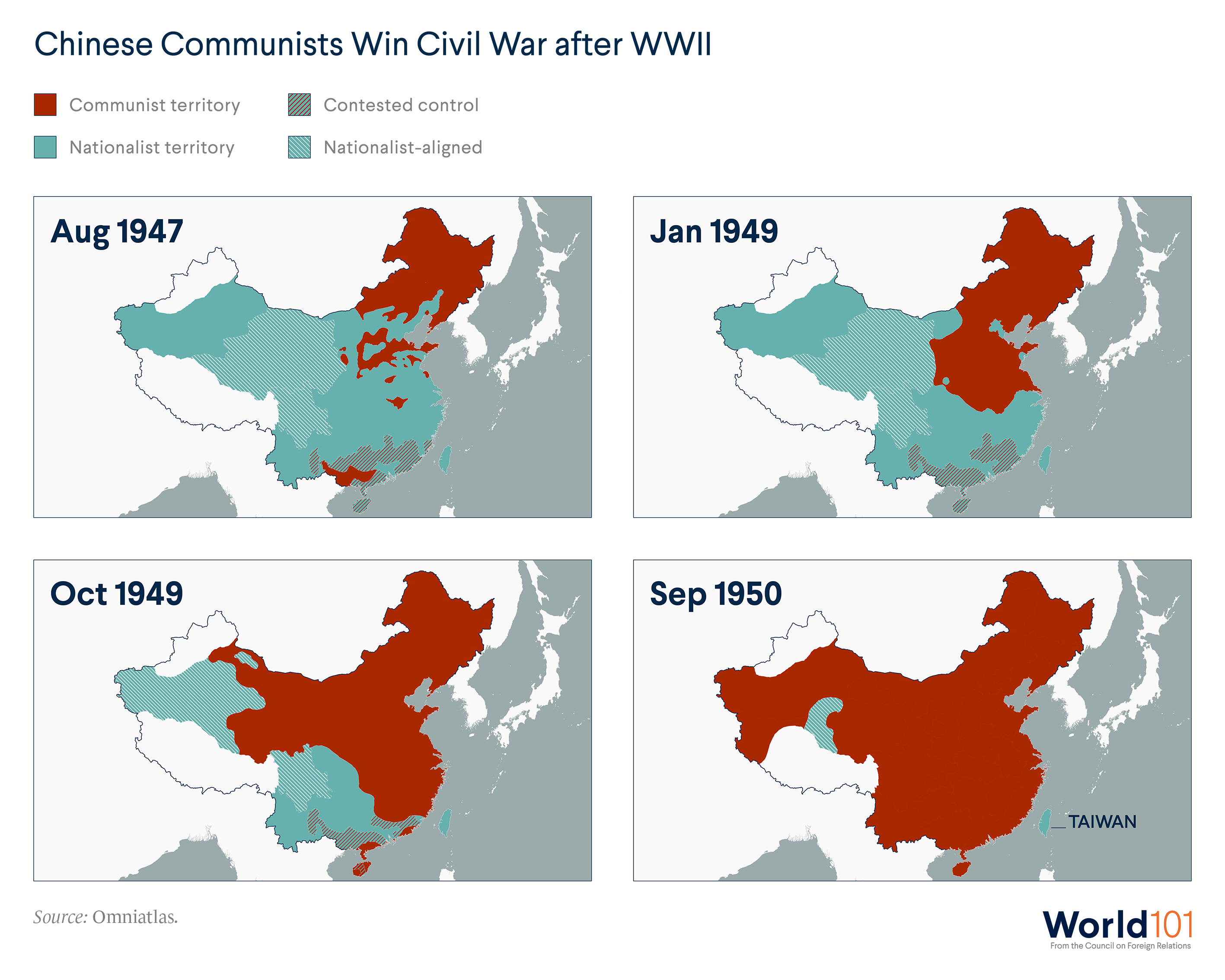

In 1912, dynastic rule ended in China, as the Republic of China, headed by the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT), replaced the ailing Qing dynasty. Led by Chiang Kai-shek, the KMT oversaw an authoritarian government and sought to stitch together a country that had fractured into territories run by warlords. Soon, however, it had to contend with a challenge from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Mao Zedong, which sought to lead a workers’ revolution and establish a communist government. A brutal civil war ensued, dividing China from 1927 to 1949. After more than twenty years of fighting and millions of deaths, the CCP emerged victorious. On October 1, 1949, Mao declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, which the Communist Party rules to this day. The KMT fled to the island of Taiwan. Now, seventy years later, a deep political rift remains as mainland China views Taiwan as a renegade province that must be brought under its control.

China’s “Century of Humiliation” Drives Global Ambition

When Mao Zedong emerged victorious in the Chinese Civil War, one of his first actions was to declare an end to his country’s “century of humiliation.” For the previous one hundred years, foreign powers—the British, French, Germans, and Japanese—had exploited the once-great Chinese empire. They had established ports in China where their citizens were not subject to Chinese law. Japan colonized large swaths of Chinese territory. But with the CCP’s rise to power in 1949, Mao pledged that China would never again be taken advantage of by foreign powers. Successive Chinese leaders have used this painful chapter to justify the CCP’s monopoly on political power, arguing that a weak and internally divided China invites foreign aggression, and only the CCP can maintain China’s unity. The Chinese government still preserves the ruins of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing, which the British destroyed in the nineteenth century, serve as a reminder of the country’s past. In addition, President Xi Jinping celebrated seventy years of communist rule in 2019 by praising the CCP for transforming China, which, for over a century, was “poor, weak, and bullied.”

Korean War Leaves a Peninsula Divided

North and South Korea share a border, a language, and over a thousand years of history as one united Korea. But, today, the two countries could not be more dissimilar. South Korea is a vibrant democracy and an economic powerhouse. Meanwhile, North Korea is an isolated, impoverished country run by one of the world’s most repressive governments. The split dates back to the end of World War II when the United States and the Soviet Union divided the peninsula, forming a communist government in the north and a capitalist one in the south. This separation was intended to be temporary, but in 1950 North Korea (with Soviet and Chinese backing) invaded the south, starting the Korean War. Fearing a communist takeover of the entire peninsula, the United States led a UN coalition that came to South Korea’s defense. After three years of fighting in which millions died, the two sides laid down their arms—but the peninsula remained divided. The two Koreas technically remain at war to this day.

Wave of Decolonization and Independence Comes to Asia

In the two decades following World War II, the number of UN-recognized countries swelled from 51 to 117. Many of these new countries were in places like sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia where a diverse patchwork of capitalist and communist, democratic and authoritarian governments quickly took shape. Some countries, like Malaysia and Myanmar, gained independence in mostly peaceful transitions of power as their colonizers were significantly weakened by the war. Others, like Indonesia and Vietnam, fought long and bloody campaigns to evict the European colonizers and secure their independence. But even with their newfound independence, East Asia’s youngest countries were not free from outside interference. World War II soon gave way to the Cold War: for the next nearly half-century, conflicts in these fledgling countries were fueled by the great power competition between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Ghosts of Dictators Past Haunt Southeast Asia

Oppressive dictators and violent military regimes ruled much of Southeast Asia throughout the better part of the mid-twentieth century. In Indonesia, just two men—Sukarno and Suharto—ruled the country from 1945 to 1998. Under their respective regimes, the government killed up to one million people in anticommunist purges and anti-crime campaigns. In nearby Philippines, U.S.-backed dictator Ferdinand Marcos ruled from 1965 to 1986, leading a regime that carried out torture, extrajudicial killings, and mass abductions. Perhaps most notoriously, Pol Pot perpetrated a genocide against millions of Cambodians, including most of the country’s Buddhist monks and ethnic minorities from 1975 to 1979. Nearly a quarter of Cambodia’s population perished in the genocide—one of the highest tolls in history. But by the end of the century, dictatorship gave way to democracy as accountable civilian governments came to power in several Southeast Asian countries. Indonesia, for example, went on to operate one of the most complex democratic elections in the world, with over 810,000 polling stations across hundreds of islands. Today, however, strongmen are once again on the rise in the region, cracking down on civil liberties like free speech and threatening to erode the foundations of these young democracies.

China’s Twentieth-Century Wars Still Strain Relations With India, Vietnam

China’s twentieth-century wars with its neighbors India and Vietnam are the source of lasting tension in the region. In 1959, India granted asylum to the Dalai Lama—the spiritual leader of Tibet—after China brutally suppressed a Tibetan uprising. India’s move infuriated China, which suspected that by providing sanctuary to the Dalai Lama and his followers, India would make rebellion in Tibet more likely and potentially even take over disputed territory along their shared border. Tensions peaked in 1962 when China attacked and quickly defeated India’s forces in this disputed territory. But nearly sixty years later, their shared border remains in dispute. In 1979, China invaded Vietnam when it seemed to be warming up to China’s communist rival, the Soviet Union, and after Vietnamese troops had overthrown a Beijing-friendly regime in neighboring Cambodia. China suffered heavy casualties in the short war and eventually withdrew. But to the Vietnamese, this war was the latest chapter in a fraught history of Chinese dynasties trying to exert control or influence over its territory. To this day, Vietnam remains wary of China’s increasing power, and the two countries have deep differences over the South China Sea. The border dispute between India and China periodically heats up with limited clashes, and India, like Vietnam, is apprehensive of China’s rise.

Tiananmen Square Massacre Demonstrates China’s Intolerance of Dissent

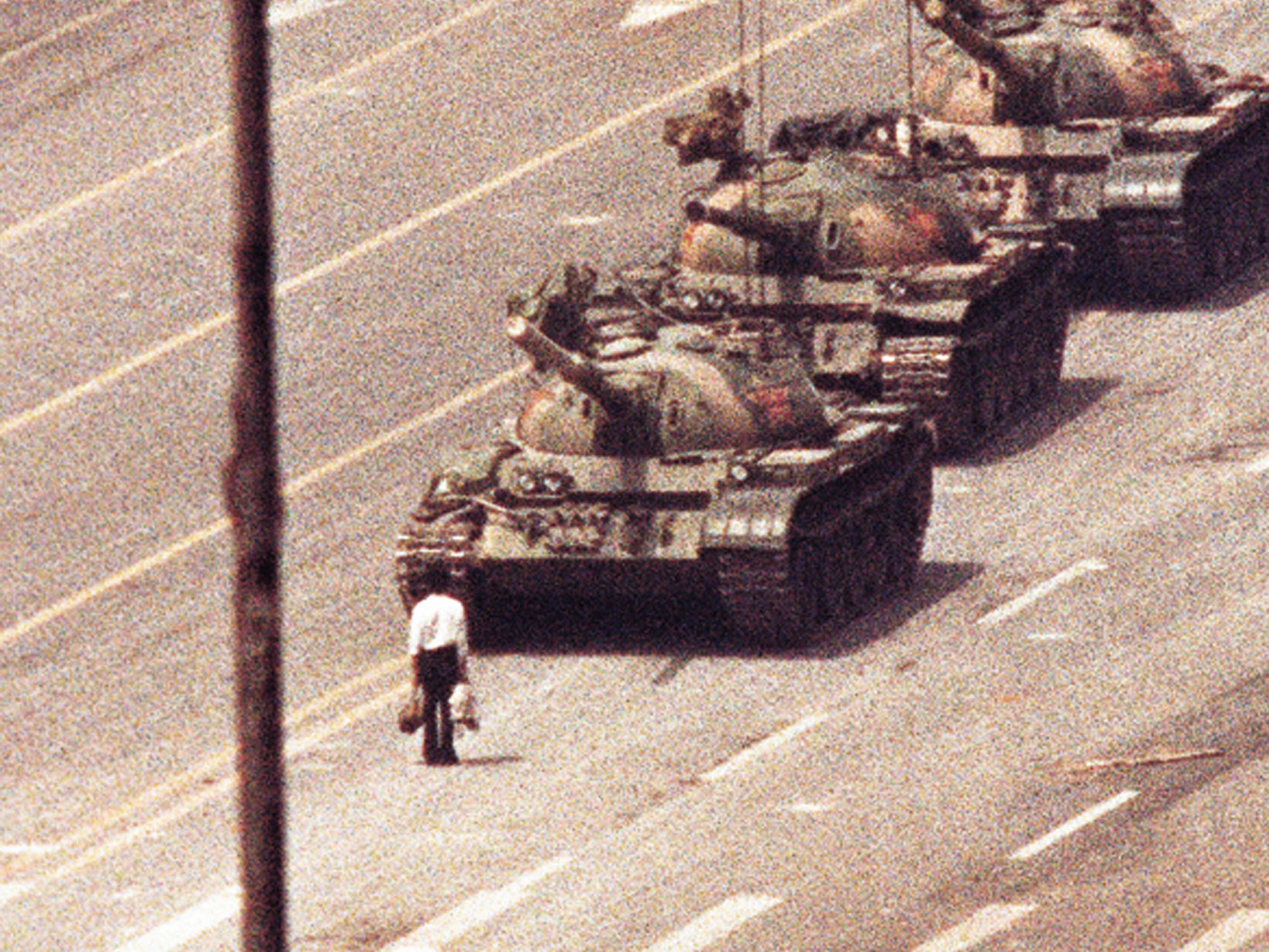

In the 1980s, hundreds of millions of people in China escaped extreme poverty owing to the country’s economic reforms. Nevertheless, vast inequality, rising food prices, and government corruption remained intractable. These concerns boiled over in May 1989 when students across China poured out into the streets demanding freedom of speech, democratic reforms, and an end to corruption among Communist Party elites. After negotiations with protesters failed, the government declared martial law and sent hundreds of thousands of troops to Beijing, where nearly one million students were demonstrating in the iconic Tiananmen Square. When protesters refused to leave, the government opened fire, killing hundreds—if not thousands—of civilians in the square and surrounding streets. The message from the Communist Party to the people was clear: political dissent would not be tolerated. The massacre remains one of the country’s most politically sensitive and censored events. All web searches originating in China that have to do with the incident are blocked, and many young Chinese people are unaware it ever happened.

British Handover of Hong Kong Leads to “One Country, Two Systems”

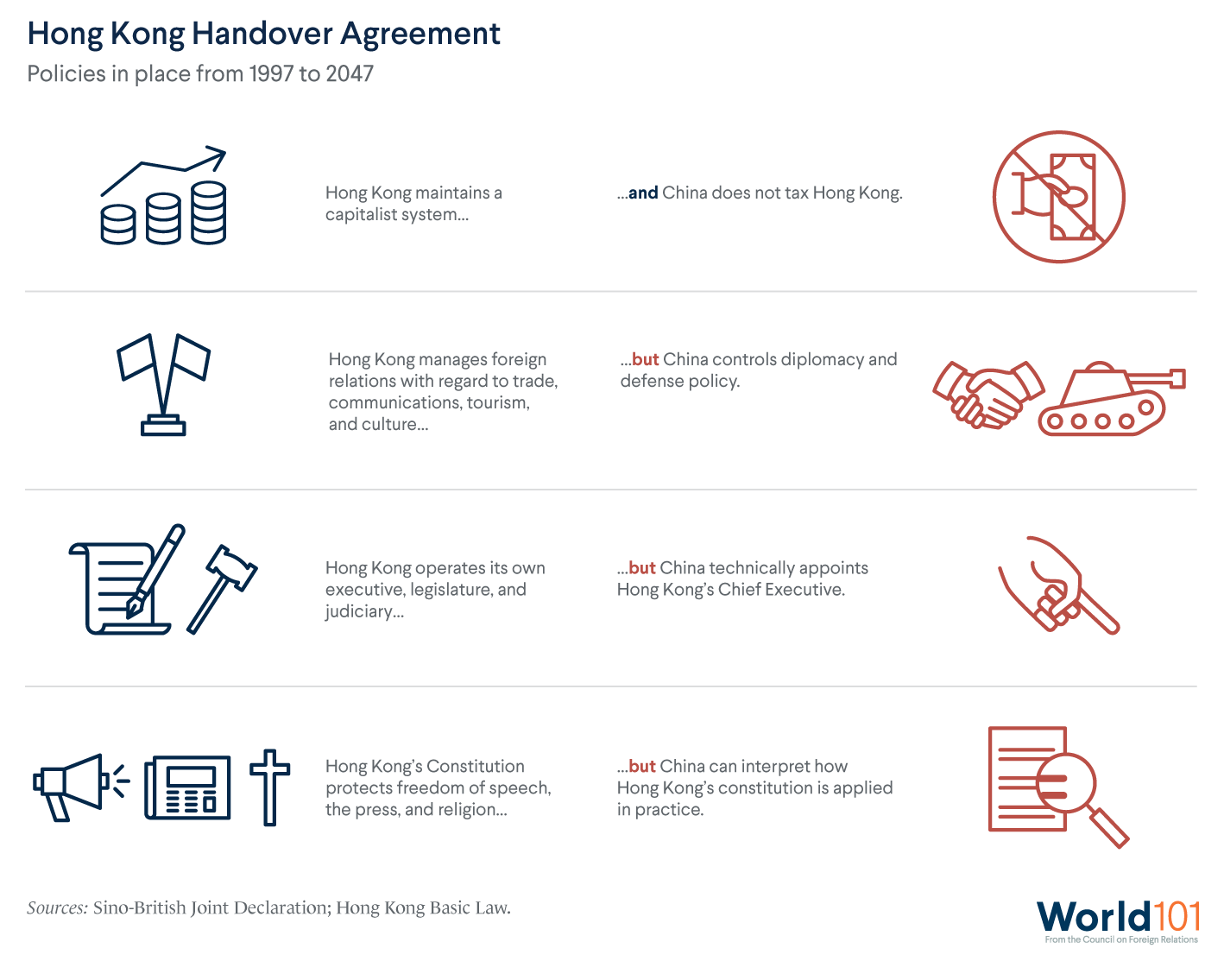

Officially, Hong Kong is part of China, but for decades it has a free press, uncensored internet, and largely democratic government, setting it apart from the mainland. The discrepancy goes back to when the British, who ruled Hong Kong since the 1800s, returned the colony to China in 1997. To protect the special status of Hong Kong—its freedoms of speech and assembly included—Britain struck a deal with Beijing: Hong Kong would officially rejoin China, but for fifty years it would have its own constitution and significant autonomy before being fully reintegrated into China in 2047. This setup was called “one country, two systems.” A similar policy applied to Macau, the former Portuguese colony which rejoined China in 1999. Beijing even hopes to eventually reunify Taiwan with the mainland through a similar arrangement, despite Taiwan’s clear rejection of the framework. However, just two decades into this policy’s implementation, Beijing is already limiting the freedoms and autonomy guaranteed to Hong Kongers, sparking widespread protests in 2014 and 2019. Beijing responded in 2020 with a new law criminalizing many forms of political opposition.