Modern History: South & Central Asia

Many of the countries that make up South and Central Asia are quite young: Pakistan and India became independent countries in 1947, Bangladesh followed in 1971, and Kazakhstan and its neighbors emerged as independent countries after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Many of the countries that make up South and Central Asia are quite young: Pakistan and India became independent countries in 1947, Bangladesh followed in 1971, and Kazakhstan and its neighbors emerged as independent countries after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. However, this part of the world does not lack history. The Indus Valley Civilization in what is now northeast Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India was an early cradle of civilization (alongside Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt), and the region is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world. Hinduism, the world’s third-largest and possibly oldest living religion, traces its origins to near modern-day Pakistan; India and Nepal gave birth to Buddhism; and Islam arrived in the region during the seventh and eighth centuries. The ancient Silk Road passed through South and Central Asia, and several empires ruled large portions of this part of the world for centuries. But by the end of the nineteenth century, most of the region was under colonial rule, with the British controlling a majority of South Asia, and the Russian Empire occupying large areas of Central Asia. This relationship to colonialism—and the subsequent disentanglement from it—set the stage for much of the region’s modern history.

East India Company Sets Stage for British in Subcontinent

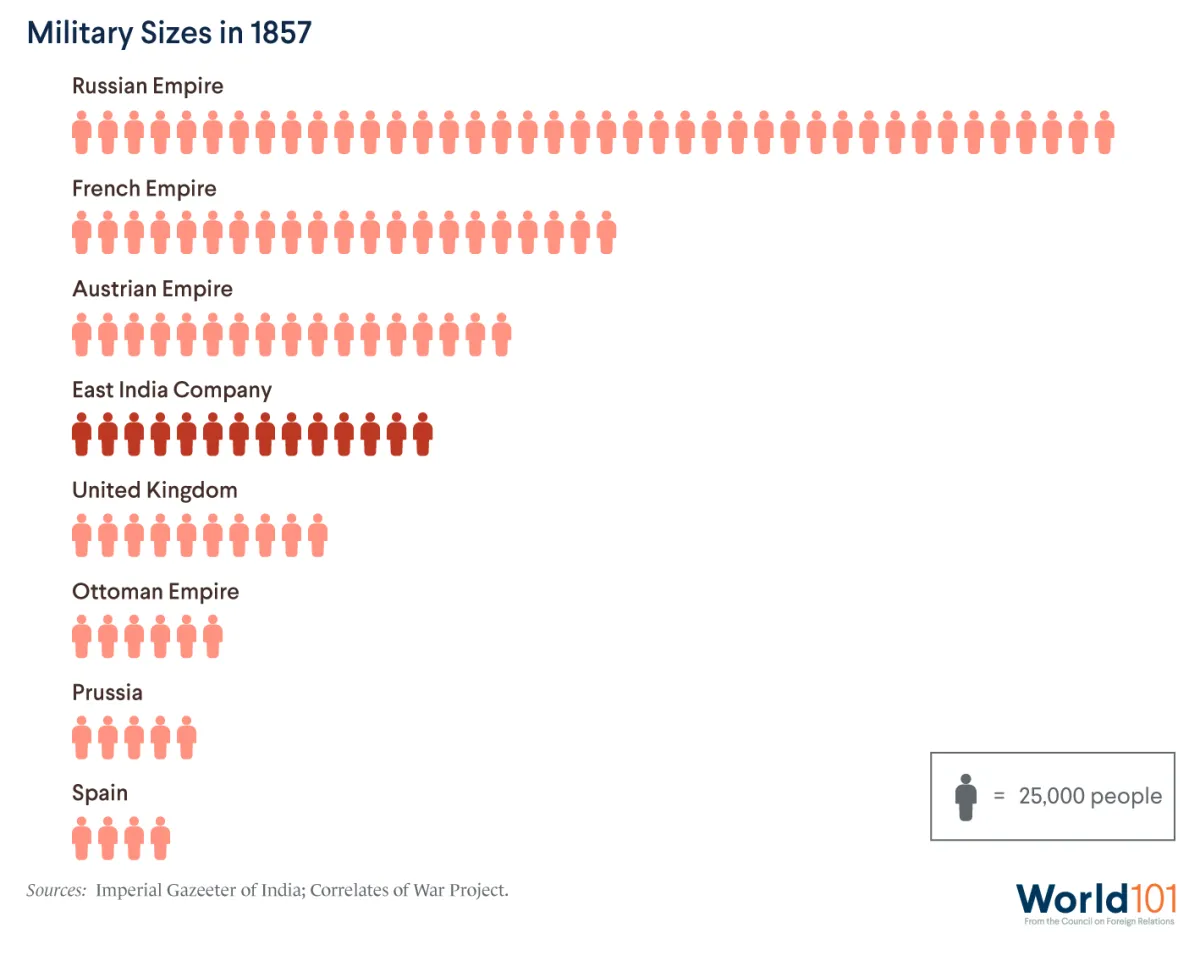

By the 1500s, Europeans were trading directly with the Indian subcontinent, an area containing most of the modern countries that we think of as South Asian: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Textiles and spices were the region’s prized commodities, and in 1600, Queen Elizabeth I approved the establishment of the East India Company, granting a few hundred merchants a monopoly on British trade with the subcontinent. Initially, the company operated from small trading outposts along the coast of modern-day India. But in its quest for profit, the company amassed a giant private army—twice the size of the British army—and took over large parts of the Indian subcontinent through conquest. At its peak, this small group of merchants ruled over two hundred million people. The British government restricted the East India Company’s autonomy over time after decades of corruption, but the company created the infrastructure the British would use after they formally colonized the region in the mid-nineteenth century.

Rebellion Leads to Formal Colonization of South Asia

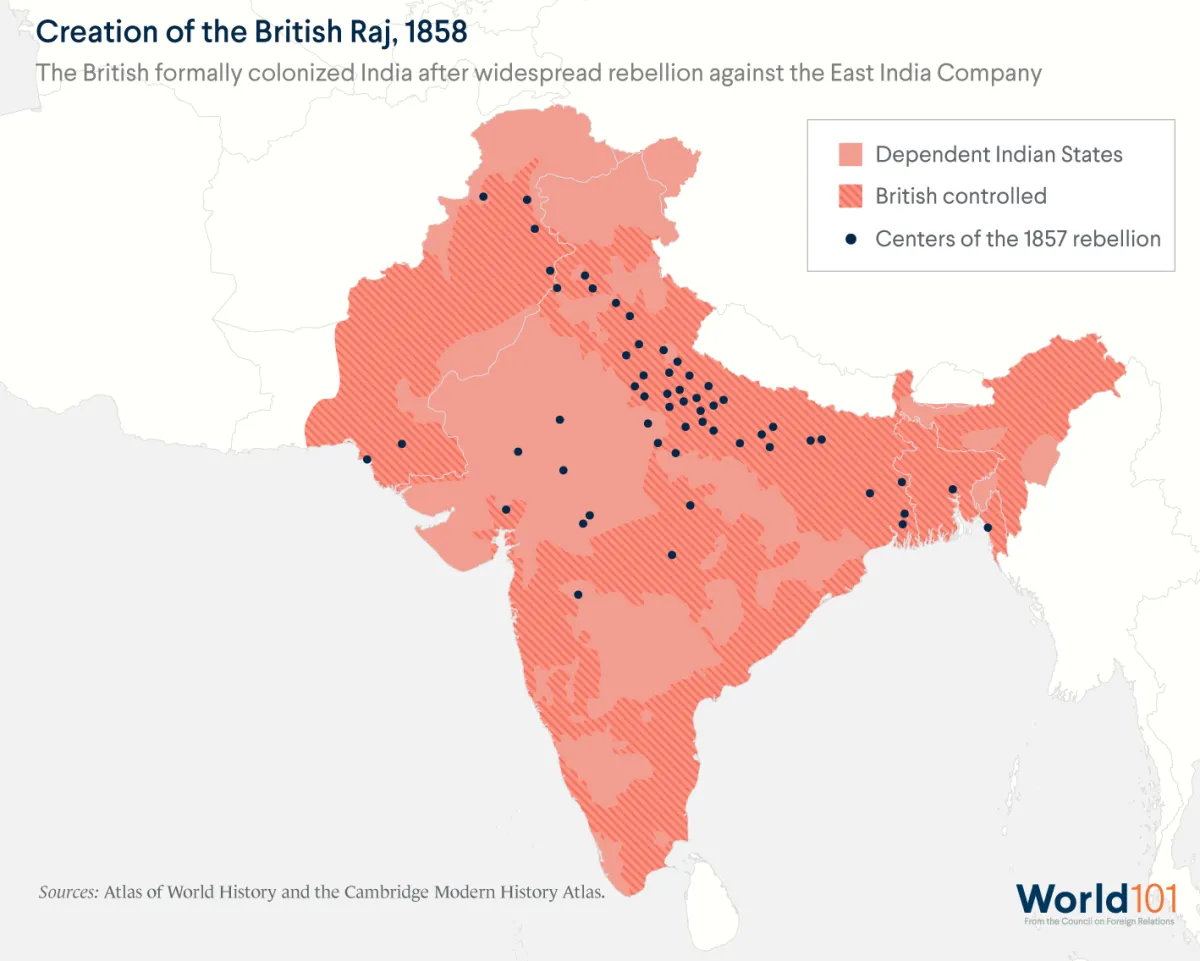

The East India Company was not popular. The native population objected to the company’s high taxes and interference with traditional Muslim inheritance laws; additionally, tribal people resisted displacement and the company’s seizing of forest land. Indian soldiers in the company’s army also resented discriminatory policies that gave preferential treatment to their European officers. Tensions peaked in 1857, when Indian soldiers accused the British of supplying rifle cartridges greased with beef and pork fat, which Hindus and Muslims viewed as a religious insult. A eighteen-month rebellion broke out, and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Indians and thousands of British. In response, the British government dissolved the East India Company and instituted direct rule in the subcontinent, thus beginning the British Raj.

Great Britain and Russia Compete for Influence in Central Asia

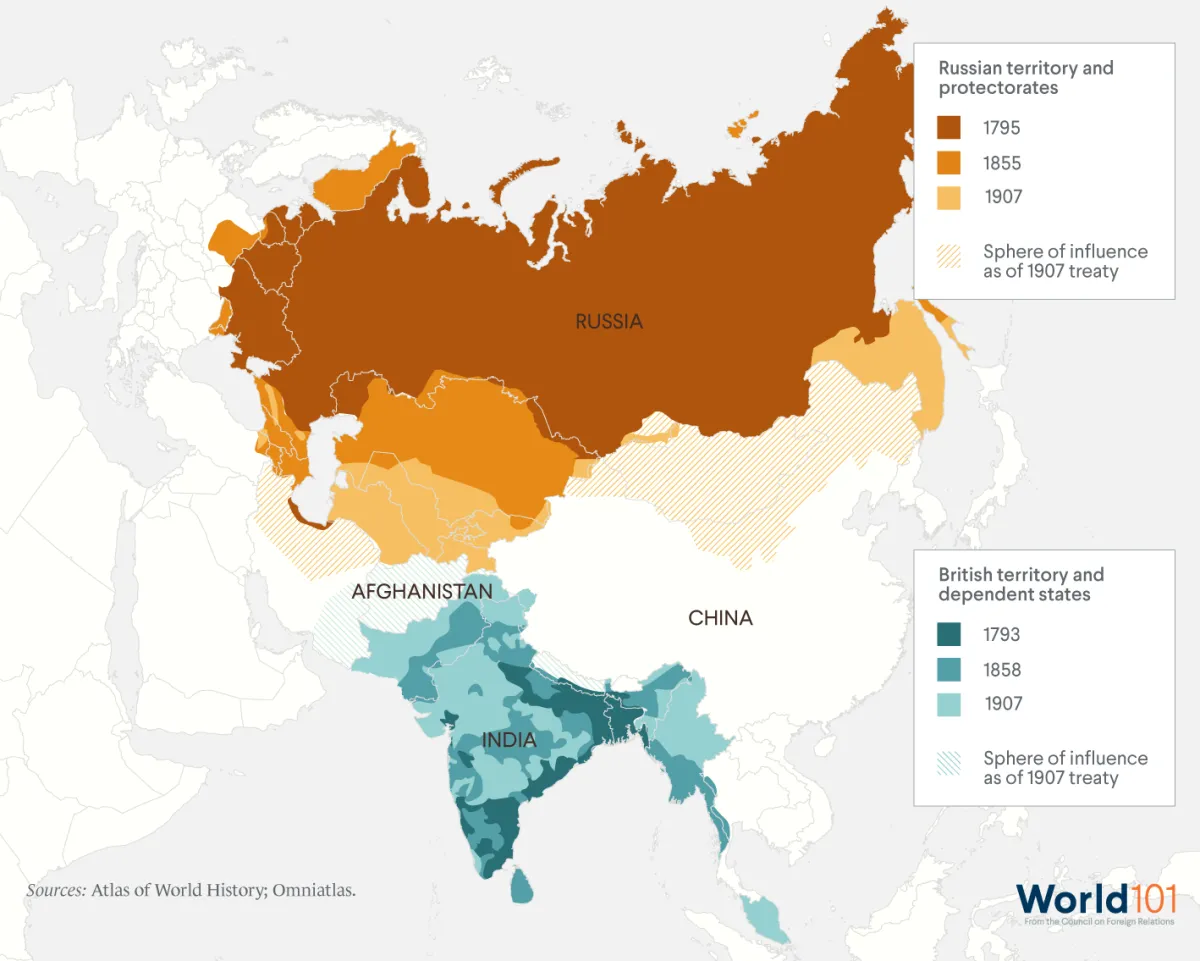

As the British gained control of the Indian subcontinent, Russia was busy taking control of the nomadic tribes and areas that dotted its southern borders. In the 1850s, Russia took direct control of Kazakhstan and by the 1890s, it began to settle Russian farmers there, displacing the nomads who had called Central Asia home for centuries. In order to protect India, which had quickly become the crown jewel of their empire, the British set their sights on creating a buffer zone that would insulate India from foreign threats. Russia, situated to the north of Central Asia, was also interested in empire-building and set its sights on the same chunk of territory. Historians refer to this intense rivalry for control of Central Asia as the Great Game, but they disagree about whether it ended in 1907, when the United Kingdom and Russia signed a series of agreements outlining their spheres of influence in the region, or ten years later, when Russian peasants, led by revolutionaries known as the Bolsheviks, revolted against the rule of Czar Nicholas II. The revolution ultimately created a communist government that incorporated virtually all of Central Asia into the newly formed Soviet Union.

Colonialism Leaves Indelible Mark on South Asia

Over time, the British government expanded the colony it had assumed from the East India Company. By 1900, it directly ruled over half the Indian subcontinent and indirectly controlled the more than five hundred kingdoms, called princely states, that made up the other half. The British employed a divide-and-rule model in India, exploiting tensions between Hindu and Muslim populations and between different castes, the levels of India's social hierarchy. They also continued the East India Company’s policies of using India’s farmable land for exportable cash crops like tea or cotton rather than food crops, which resulted in famines that killed millions of Indians during the Raj. The legacy of British colonialism can still be seen across the subcontinent today: the prioritization of Britain’s economy over that of the colony led to the drain of wealth and long-lasting underdevelopment of infrastructure in India. However, arguably the most enduring legacy of the British came during their hasty exit from the region after World War II, sowing the seeds of what is one of the biggest geopolitical rivalries today.

Pakistan Is Born as British Exit Subcontinent

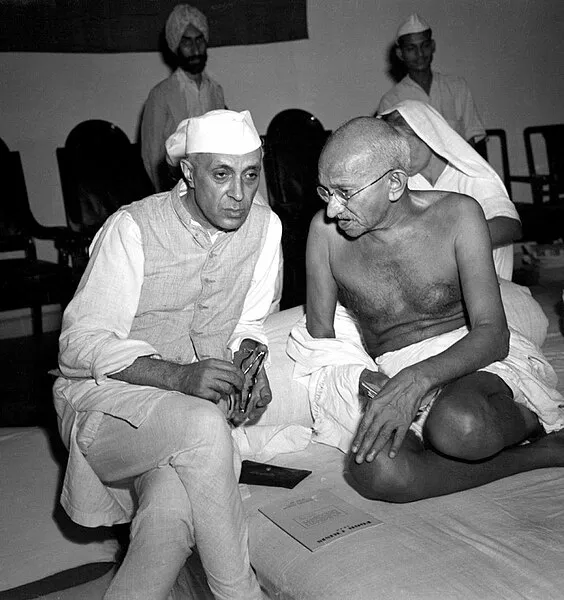

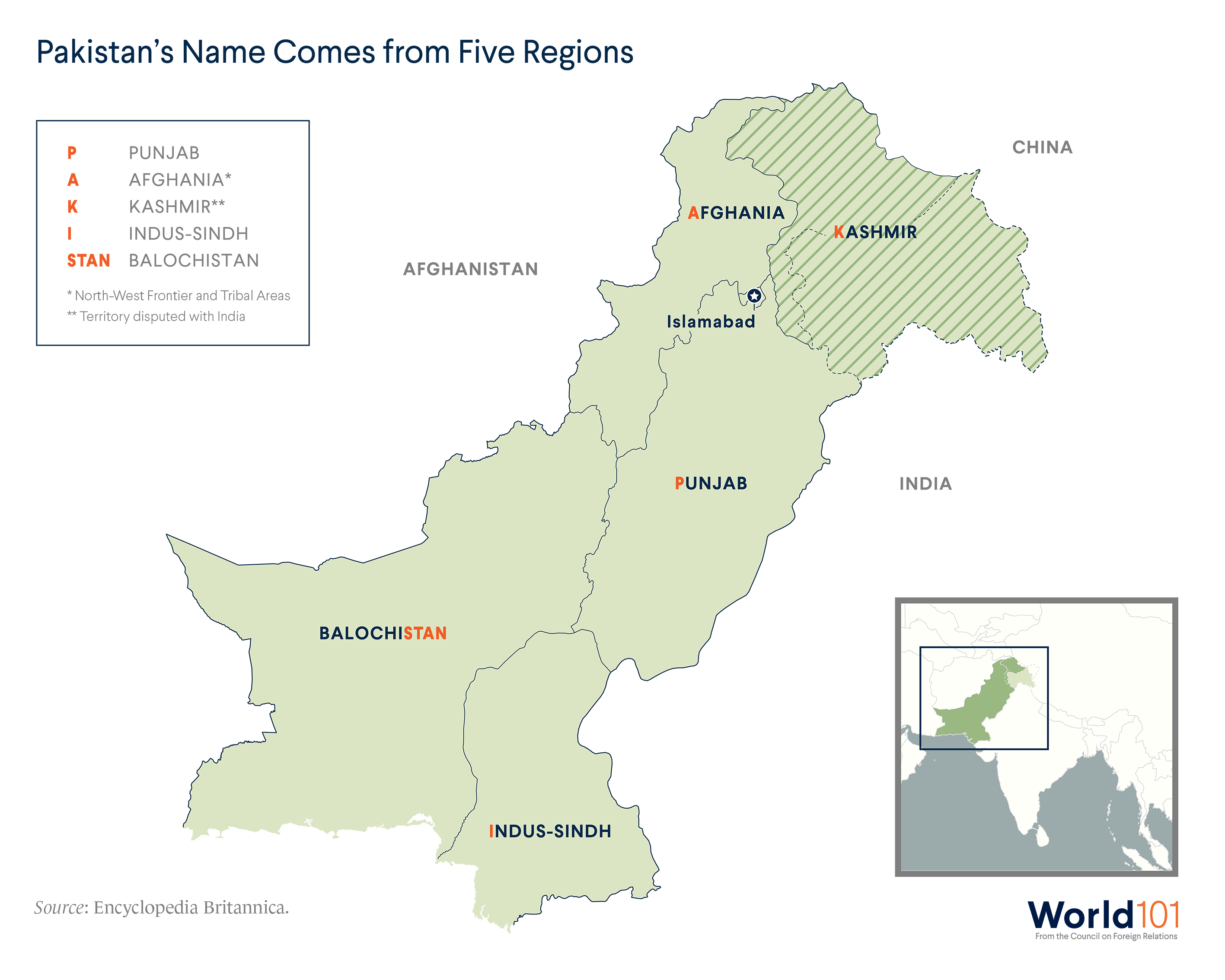

Independence became a real possibility by the early twentieth century as the British redirected resources to fight in the two world wars and as Indians of all faiths—led by activists like Mahatma Gandhi—protested for their freedom. While most Indian leaders pushed for independence, a small group known as the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, worried about becoming a vulnerable minority in an independent, democratic, and majority-Hindu India. The group vaguely proposed that the British should grant autonomy to a Muslim state known as Pakistan, comprising the Muslim-majority regions of British India. (Pakistan itself was an acronym for those regions: Punjab, Afghan province, Kashmir, Sindh, and the tan in Balochistan.) But the Muslim League did not propose complete sovereignty or outline geographic boundaries. Rather, the proposal for Pakistan was supposed to be a political bargaining chip to secure Muslims’ rights. Most Hindus and Sikhs argued that an undivided India would be stronger. Even large groups of Muslims believed that they would be protected in a secular India, preferring to stay in their hometowns rather than move hundreds of miles to a new country. Ultimately, the British—unable to sustain their huge colony after World War II and eager to exit India—accepted the Pakistan proposal. When the British departed the subcontinent, they divided it into two newly independent countries. On August 14, 1947, Pakistan was born. One day later, India celebrated its independence.

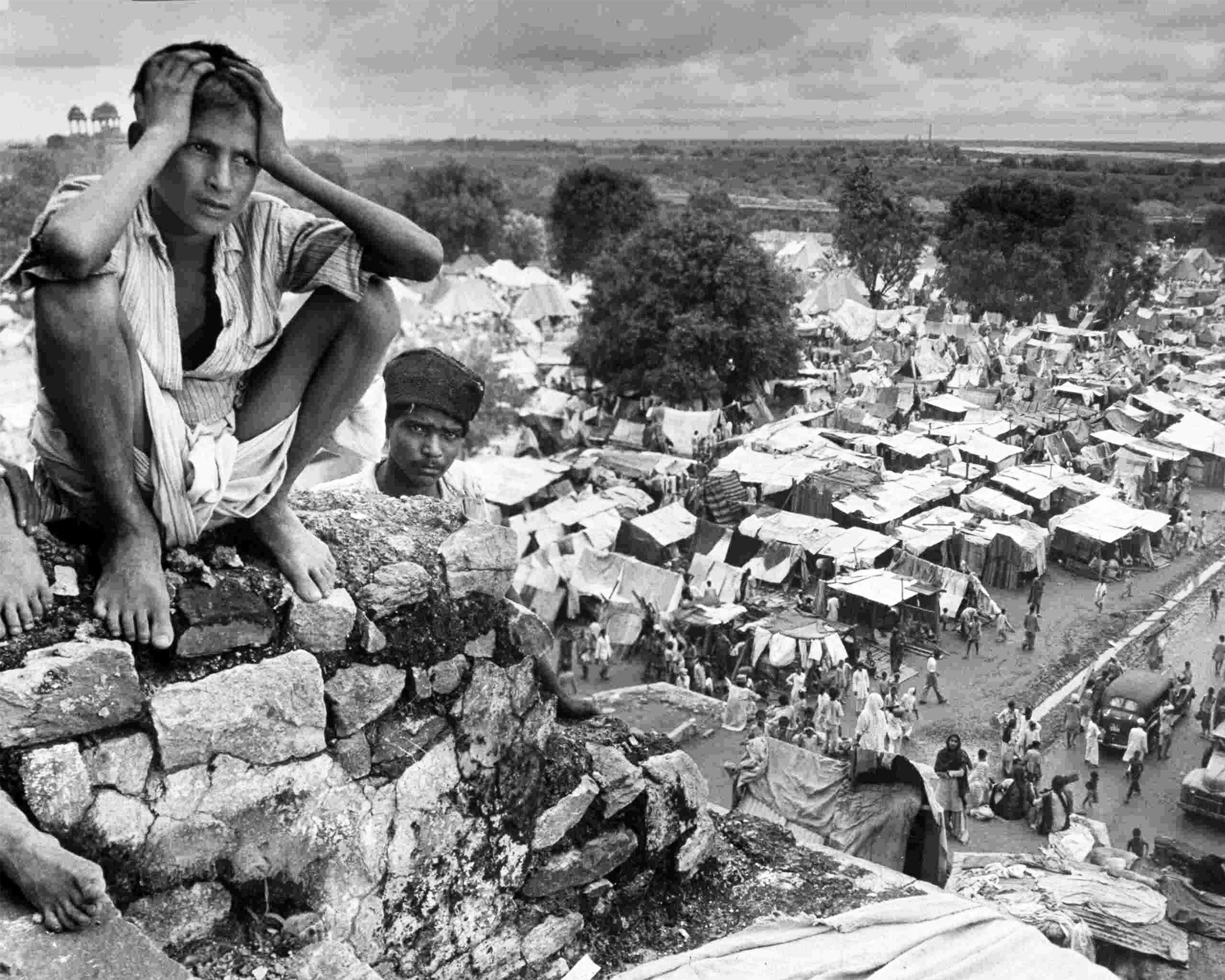

Roots of India-Pakistan Antagonism Lie in Partition

What followed independence is known as the Partition of India, a deeply painful period in the region’s history when millions of Muslims migrated to the newly created Pakistan and millions of Hindus and Sikhs fled to India. (Sikhism is the major religion in the northern Indian region of Punjab.) During partition, killing, arson, abductions, and sexual violence were widespread. At least ten million Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs became refugees, and at least five hundred thousand people across the subcontinent died in the violence. Since the trauma of partition, Indians and Pakistanis have maintained a deep mistrust of each other. The countries have fought three major wars against each other, including one in 1971 that resulted in the creation of an independent country—Bangladesh—which had been the eastern section of Pakistan. The mistrust that defines the India-Pakistan relationship continues today, including over the question of the disputed area of Kashmir.

How Kashmir Became South Asia’s Most Contested Region

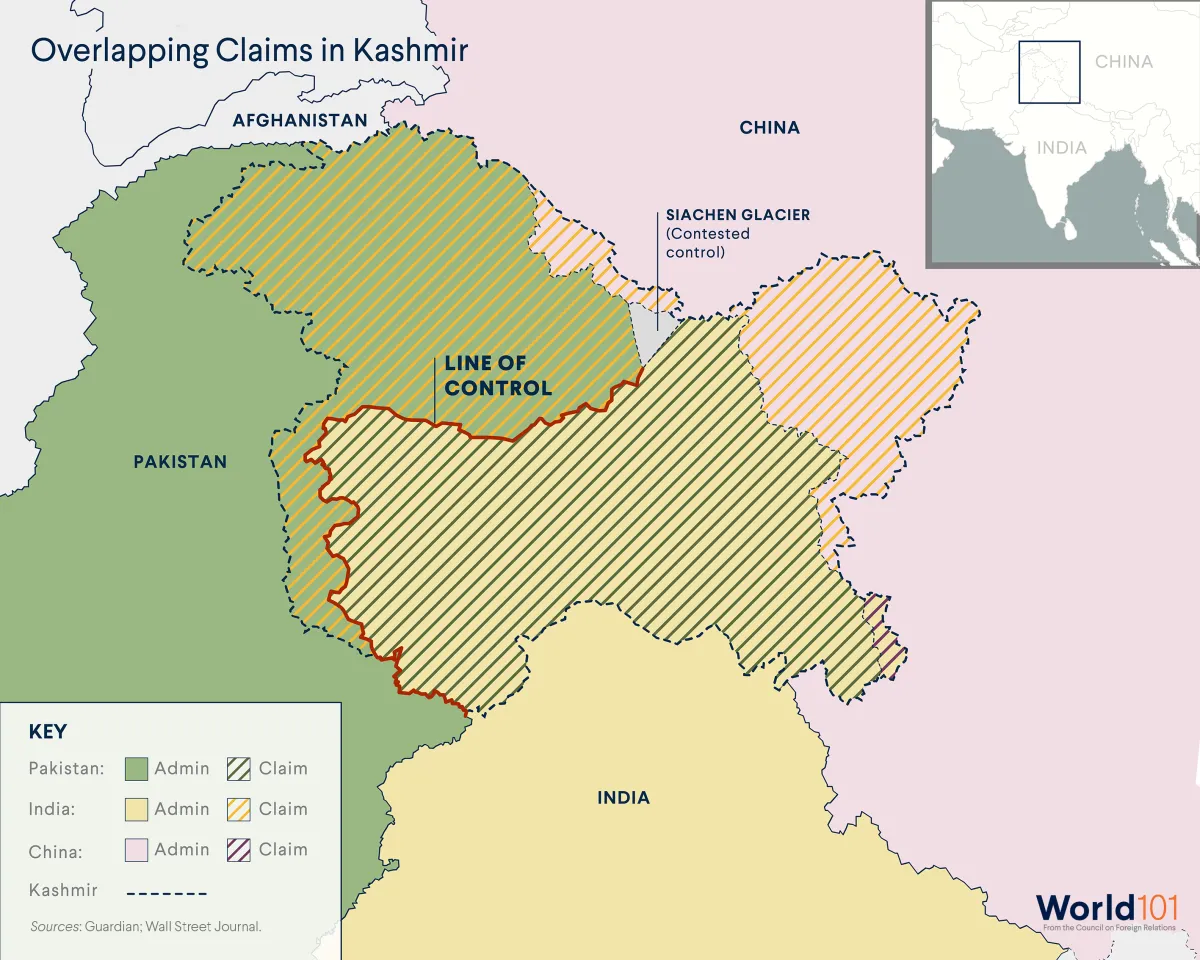

When the British partitioned the subcontinent, hundreds of semi-independent kingdoms (called princely states) outside direct colonial administration had to choose between joining India or Pakistan. The decision was typically straightforward and fell along religious and geographic lines: Hindu-majority states joined India, while Muslim-majority states opted for Pakistan. But Kashmir, the largest of these territories, was in a tricky spot. It had a Muslim-majority population but a Hindu ruler. Initially, the ruler of Kashmir decided to stay independent. But tribesmen from Pakistan invaded Kashmir in an attempt to force it to join Pakistan. In response, the Kashmiri monarch signed a deal: Kashmir would join India—with the understanding that Kashmir would enjoy significant autonomy—in exchange for protection. Pakistan rejected this decision, and just months after independence, India and Pakistan went to war over Kashmir. By the end of the yearlong war, India controlled two-thirds of Kashmir and Pakistan had the rest. To this day, that cease-fire line (called the Line of Control) divides Kashmir, with India and Pakistan administering their side of the boundary. India and China also fought a war in 1962 partially over a northern part of the region that is adjacent to Tibet. All three countries that have competing stakes in Kashmir possess nuclear weapons, making this area one of the world’s most volatile hot spots.

Bangladesh Emerges From 1971 War, Prompts Nuclear Pursuit

Upon independence, Pakistan consisted of two wings—East and West Pakistan—separated by 1,300 miles of Indian territory. But West Pakistan, where the government was based, was much more powerful and denied East Pakistan various economic, linguistic, cultural, and political rights. After decades of mounting resentment against West Pakistan’s domination, East Pakistanis intensified independence protests in 1971. In response, troops from West Pakistan occupied the area to prevent it from seceding and committed genocide against their own citizens, killing up to three million people. India—which faced a humanitarian crisis with more than ten million refugees from East Pakistan entering its borders—intervened on behalf of East Pakistanis and ultimately pushed West Pakistani troops out of the area, and an independent Bangladesh was born. While Bangladeshis celebrated their independence, the dismembering of half of Pakistan’s territory was devastating for Pakistan and seemingly confirmed its suspicion that India was an existential threat. Prompted by the loss of its eastern wing, Pakistan began work on developing nuclear weapons the following year to defend itself against India in the future. Thus began the nuclear race in South Asia: when India conducted its first nuclear test in 1974, Pakistan accelerated its own program, and both countries had publicly acquired the bomb by 1998.

Soviet-Afghanistan War Draws the United States Into Region

At the crossroads of South and Central Asia lies one of the region’s other enduring hot spots. Over the past two hundred years, many countries have tried and failed to conquer Afghanistan, a landlocked mountainous country at the strategic intersection of India, China, and the Middle East. Its epithet, “the graveyard of empires,” gives a sense of how past invasions have gone. In 1979, during the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union learned this lesson when it sent troops to support Afghanistan’s unpopular communist government against anticommunist Muslim insurgency groups. Collectively known as the mujahideen, these groups opposed the land reforms and secular policies proposed by their new government and attracted fighters from across the Muslim world to fight with them. The mujahideen received support from many foreign governments, including the United States, which was eager to push back against its archrival, the Soviet Union. The United States, using a base in Pakistan, ultimately helped the mujahideen push the Soviets out of Afghanistan after nine years of war, but by then an estimated one million civilians and tens of thousands of mujahideen fighters, Afghan soldiers, and Soviet troops had died.

Soviet Collapse in Central Asia and the Legacy of the Cold War

The Soviet Union was composed of fifteen republics: large states like Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, each with a distinct ethnic nationality. In theory, they were equal, but in practice, power was concentrated in Moscow. During Soviet rule, the Central Asian republics were used almost exclusively for extracting minerals, oil, and gas; growing cotton; and testing nuclear weapons. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan became independent countries facing enormous economic challenges—how to untangle their economies from the Russian economy, how to deal with soaring inflation, and how to exist without Soviet subsidies. They went about trying to diversify their economies in the face of strong headwinds: they were landlocked, surrounded by security threats that often thwarted investment or the tourism industry from taking hold; faced environmental degradation from years of nuclear testing; were experiencing huge influxes of new immigrants; and had weak national institutions. As a result, the countries of Central Asia have had a slow transition to market economies and Russia continues to serve as a major trading partner and weapons provider.

Taliban Grow From Afghanistan’s Power Vacuum

After the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, a power vacuum took hold. Feuding factions ravaged the country yet again through seven subsequent years of civil war until one group—the Taliban—emerged as the strongest, with funding and support from neighboring Pakistan. The Taliban are an ethnically Pashtun, Islamic fundamentalist group with roots in the anti-Soviet mujahideen movement. The group leveraged its battlefield gains into political power, eventually governing most of the country and imposing a strict interpretation of Islamic law. Its Ministry of Virtue and Vice banned television and musical instruments and outlawed education for women, who were required to wear full-body coverings. In its quest to control the entire country, the Taliban killed thousands of civilians, burned entire villages, and destroyed Afghanistan’s farmlands. Ultimately, the Taliban government provided safe haven to extremist groups such as the 9/11 architects, al-Qaeda, prompting the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.