What Is the World Trade Organization?

What is the WTO? Learn how the World Trade Organization manages the rules for international trade and why it's failing to address today’s most pressing issues.

Teaching Resources—Global Governance: Introduction (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

What does the WTO do?

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an international institution created in 1995. The WTO regulates trade between nations. A replacement for the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the WTO manages the rules of international trade. The WTO seeks to ensure fair and equitable treatment for its 164 members by conducting negotiations, lowering trade barriers, and settling disputes.

World leaders have called out the WTO in recent years, criticizing the institution responsible for creating and enforcing global trade rules. Some policymakers condemn the WTO’s inability to address China’s unfair economic practices, its failure to adapt to a digital world, and even its role in deepening global inequality.

The WTO now faces unprecedented criticism and significantly diminished global influence at a time when countries increasingly rely on moving goods, services, and information across borders.

This resource breaks down the global trade system. It introduces the achievements and shortcomings of its chief regulator, and considers what eliminating the WTO could mean for global order.

Why do countries trade in the first place?

In today’s global era, international trade is essential. No country can produce everything it needs at reasonable prices within its borders. Instead, a country will be richer if it makes what it is best at and imports what it is not as good at producing. That idea is known as comparative advantage. The United States thus sells airplanes to countries around the world but imports products like coffee and tea. Whether it’s importing fuel, food, or electronics, a country needs international trade to function.

Most economists also believe that free trade—that is, trade without government interference—increases the variety of goods, reduces their cost, and generates job growth. Furthermore, free trade makes the world safer, as economically interdependent countries are less likely to go to war.

Learn more about international trade.

Despite those benefits, governments still interfere in trade. Governments may intervene to give domestic industries a leg up on foreign competition or to punish other countries for political reasons. That interference can include tariffs (taxes on imports), subsidies (financial boosts to domestic industries that make products artificially cheaper), and quotas (hard limits on how much of a particular product a country can import).

If a government erects one of those trade barriers, another government will likely retaliate so that its own domestic industries do not become disadvantaged. Such tit-for-tat escalations leave both countries worse off and make perfectly free trade difficult to attain.

How was the WTO created?

After World War II, countries tried to promote international economic cooperation by creating a global trade organization. Although that effort was unsuccessful, twenty-three countries ultimately signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. That agreement established a new rules-based trading system to lower trade barriers and create rules for free trade.

The GATT largely succeeded in those efforts. Global tariffs fell from an average of over 20 percent in 1947 to under 9 percent in 1994 as membership grew to 128 countries. However, the GATT was just an agreement. It was not an organization with robust regulatory and enforcement capabilities.

Thus, in 1995, GATT signatories shifted the responsibilities and membership of the original trade agreement to a new institution, the WTO. The WTO implemented procedures for resolving disputes between countries and, for the first time, created trade rules related to intellectual property and services.

Do WTO members have trade disputes?

The WTO’s membership now stands at 164 countries, accounting for 98 percent of international trade.

Unlike other international institutions that struggle to enforce rules, the WTO has power to hold countries to account. WTO members face penalties, including retaliatory tariffs, if they violate trade rules. The WTO permits a country suffering from another country’s tariffs to respond with tariffs of its own. Since 1995, the WTO has helped resolve hundreds of trade disputes, and nearly 90 percent of the time, governments comply with the organization’s rulings.

For decades, the GATT and WTO have contributed to the immense growth of international trade. This growth in trade has increased consumers’ access to more affordable products and inspired innovation as companies compete on the international market. Today, the WTO faces several major challenges in carrying out its mission.

Has the WTO been good or bad for the world economy?

That depends on how the WTO's job is defined.

If the WTO’s chief duty is expanding free trade, then it has been largely successful. Because of the GATT and WTO, international trade now occurs in a relatively low-tariff world. Average tariffs today are under 3 percent—down from more than 20 percent in 1947.

Additionally, the dollar value of international trade has quadrupled since the WTO’s inception. Global value chains—in which one product is assembled from parts and labor from multiple countries—now account for over 70 percent of all manufactured goods. Although neither the GATT nor the WTO is fully responsible for increased globalization, they helped create its necessary conditions.

However, globalization and free trade have their drawbacks. These include the potential for economic inequality and job loss. While technological advances like automation make the precise role of globalization and free trade difficult to determine, an estimated two million American jobs were lost between 1999 and 2011 due to competition from China. Some critics—such as unions, labor rights groups, and environmentalists—argue that free trade moves jobs to countries with little government oversight, which can result in exploitative practices.

In the WTO’s capacity as the world’s trade legislator—an institution responsible for creating laws—it gets lower marks. For years, the WTO has been unable to pass new rules on modern issues, including digital trade, ecommerce, and public health standards for genetically modified foods. After fourteen years of talks, the WTO’s latest negotiations, known as the Doha Round, failed to establish new regulations on politically sensitive issues such as agricultural subsidies and other matters affecting developing countries. This gridlock is largely due to the WTO requiring consensus among its 164 members to pass most new trade laws.

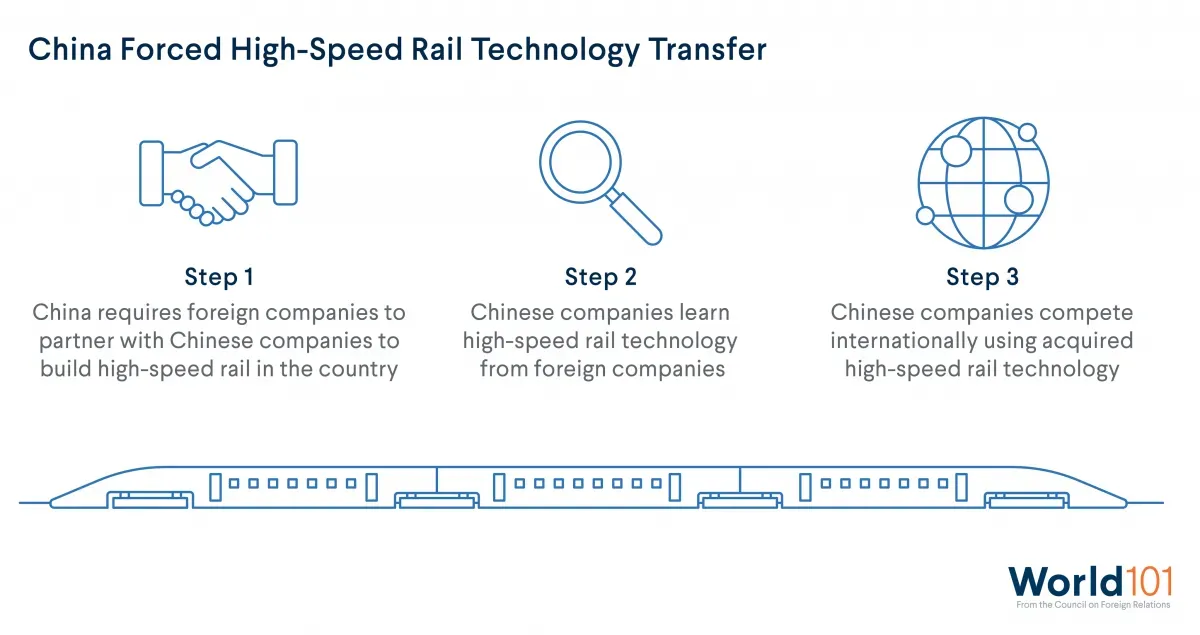

The WTO also struggles to perform its third job—rule enforcement—particularly with China. Since joining the WTO in 2001, China has flouted global trade rules by providing extensive support to its domestic industries and stealing technology and other intellectual property. It has faced few, if any, consequences for its actions. Further, the WTO still recognizes China as a developing country. This provides a special status that affords China certain benefits—despite its having the world’s second-largest economy.

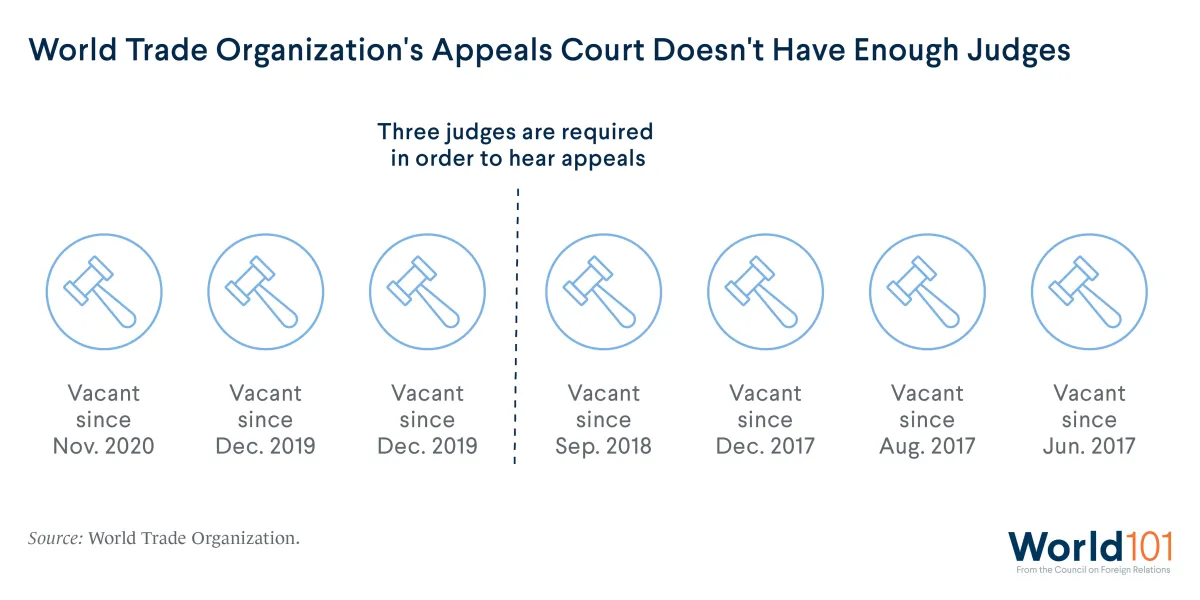

Finally, in its fourth role as chief referee of global trade disputes, the WTO has been sputtering. Critics highlight the WTO’s yearslong process to resolve disputes. Critics also point to the outsize power judges have to single-handedly create new trade rules. For those reasons, the United States has vetoed the appointment of new judges to the WTO’s highest court since 2017. There have been no appellate body members since 2020, when the last judge's term expired. The lack of judges forces the WTO’s dispute resolution process to shut down. Many experts argue that the United States should enlist its allies and partners in reforming the institution to hold China to account.

What is the future of the WTO?

The GATT and WTO have been a boon for global trade. They have improved living standards for billions of people. But, today, the WTO faces many challenges. It struggles to pass new trade rules, fails to hold bad actors accountable, and is unable to resolve disputes.

Instead of negotiating trade rules through the WTO, countries are turning to bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs), which have increased significantly since 1990.

RTAs accomplish much of the WTO’s mission. However, without an international organization meaningfully regulating free trade, the likelihood of unrestrained and costly trade wars increases.

The WTO will require major reforms to tackle today’s toughest challenges. Trade experts [PDF] point first and foremost to the need to reform the institution’s highest court by making it more efficient and accountable. Doing so would restore one of the WTO’s central functions while allowing countries to pursue broader organizational reforms. But until such reforms occur, the WTO will struggle to fulfill its mandate at a time when the world needs an international trade organization more than ever.