Understanding Northern Ireland’s ‘Troubles’

More than twenty years after the Good Friday Agreement was signed, challenges remain for Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland long after the conflict ended.

Between the late 1960s and the late 1990s, a violent struggle engulfed Northern Ireland. Shootings, bombings, and assassinations were commonplace. People—divided along religious and political lines—battled over the future of the region. The conflict centered around whether Northern Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom or split away to reunite with the Republic of Ireland.

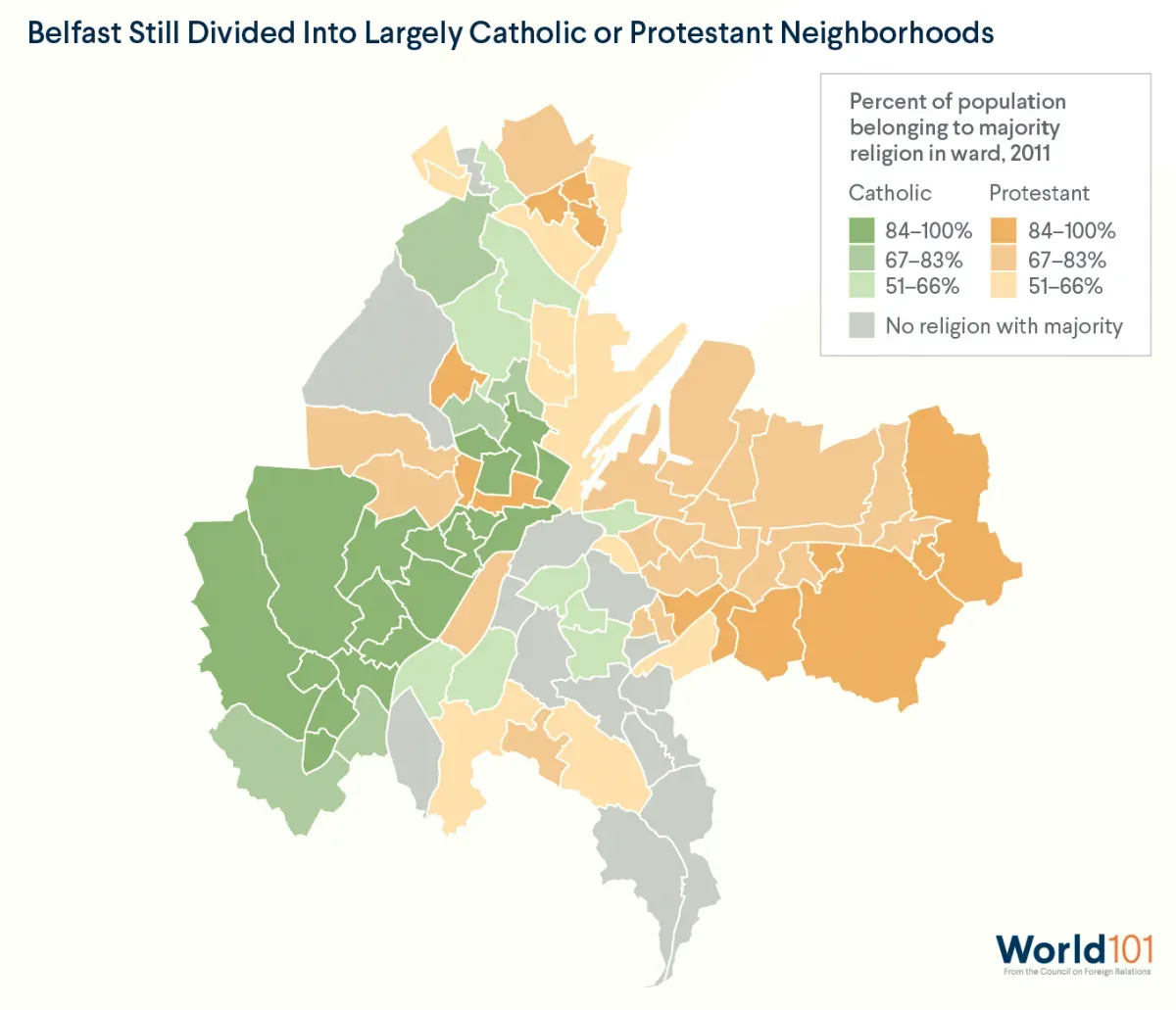

More than 3,500 people died during those decades of conflict known as the Troubles. And though the period largely ended with a peace deal in 1998, many of Northern Ireland’s Catholics and Protestants continue to live mostly separate lives. More than 90 percent of children go to schools segregated by religion. Some neighborhoods remain physically divided. Nearly one hundred barriers [PDF], including so-called peace walls, still crosscut the capital, Belfast.

Northern Ireland’s continued segregation more than twenty years after the Troubles ended reveals something about the nature of conflict more broadly: it is like a garden weed with deep roots. Even when a country achieves some semblance of peace, the root causes of conflict often remain. This resource examines Northern Ireland’s recent history, illustrating what happens after conflict ends—and what societal challenges are left in its wake.

What were the Troubles?

Like many conflicts, Northern Ireland’s Troubles have a long history tied up in religion, ethnicity, and politics. The Troubles’ seeds were planted centuries ago when British Protestants first subjugated Ireland’s native Catholic population.

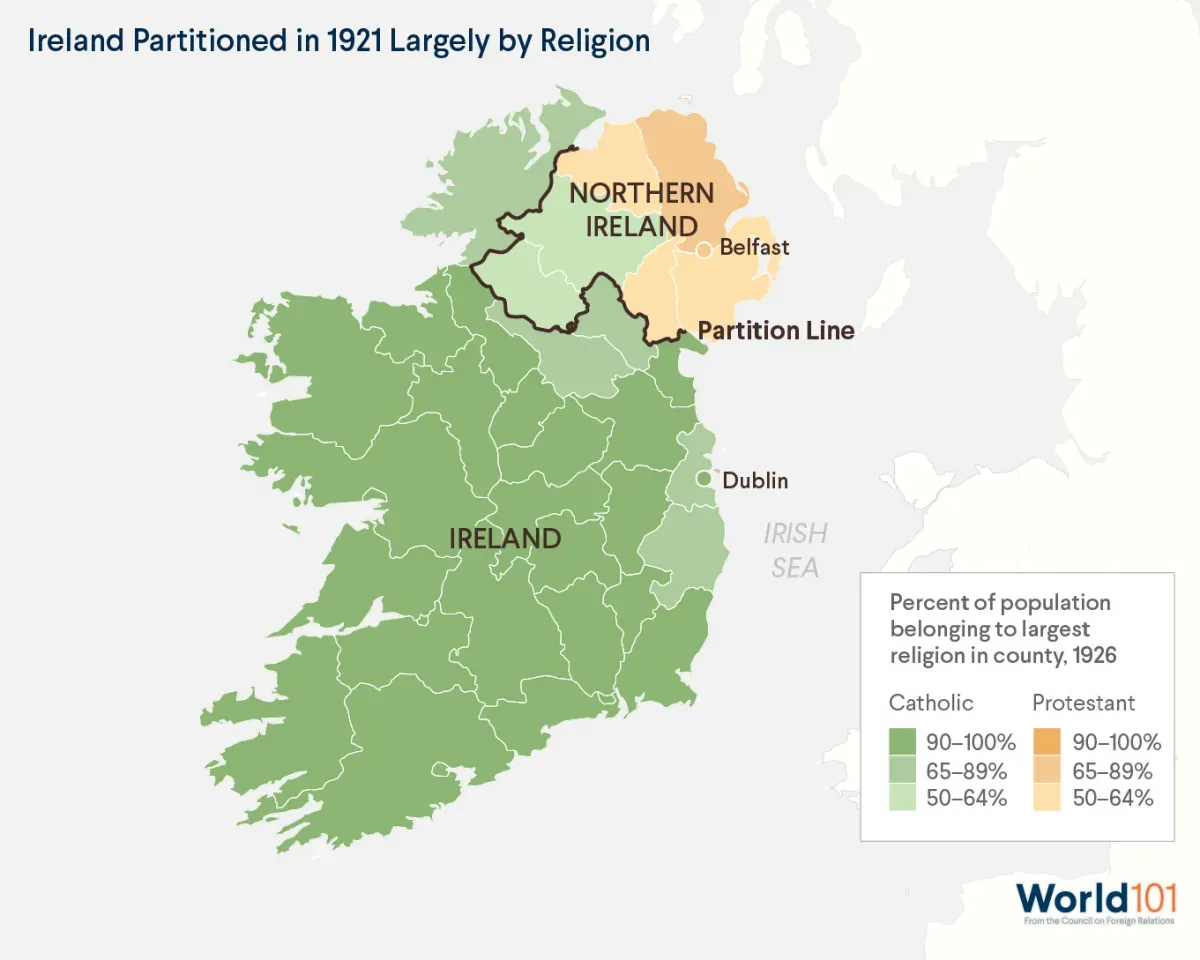

But it wasn’t until the early 1920s, after a successful push for Irish independence, that the island fractured in two. The Republic of Ireland would eventually make up much of the island, while six counties in the northeast remained part of the United Kingdom. This territory became known as Northern Ireland.

In Northern Ireland, British Protestants made up most of the population and held most of the region’s political power. (Meanwhile, the Republic of Ireland was and remains predominantly Catholic.) In the 1960s, Northern Ireland’s Catholic minority was frustrated over issues like unequal access to housing and jobs; that discontent led to a civil rights movement, which the mostly Protestant police violently suppressed. In 1969, the British deployed their military to quell the unrest. The situation proved a tinderbox that quickly exploded.

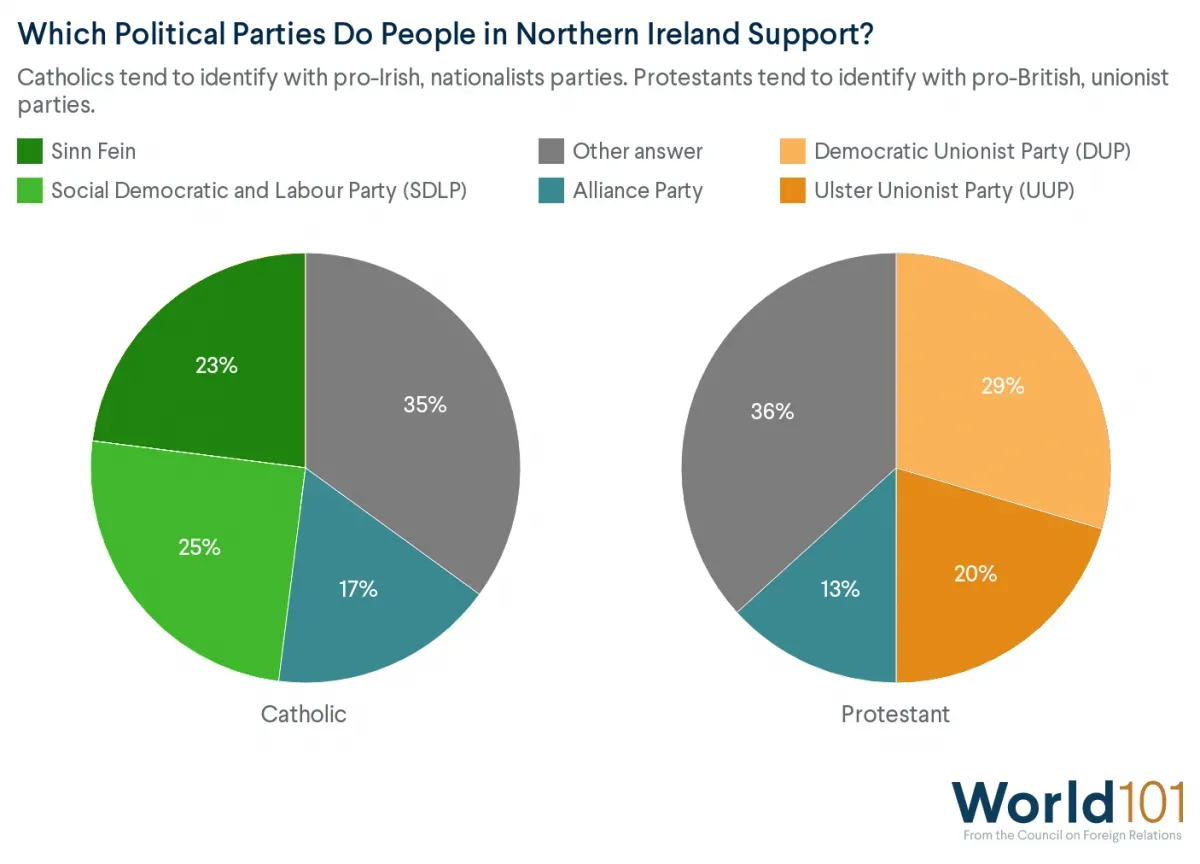

People were divided not just by their faith and culture but also by their desires for Northern Ireland’s political future. Catholics mainly identified as pro-Irish and nationalist; they wanted Northern Ireland to unite with the Republic of Ireland. Protestants largely called themselves pro-British and unionist; they vehemently opposed leaving the United Kingdom.

Those disagreements erupted into terrorism. Extreme factions of both communities bombed city centers and assassinated members of rival groups. Paramilitaries—groups that function like a military but aren’t formally part of a country’s armed forces—were responsible for much of the violence during those years. For three decades, explosions, shootings, and terror plagued Northern Ireland. The conflict even spilled into the Republic of Ireland and England.

By the 1990s, the situation was changing. A paramilitary group called the provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) had long tried to forcefully reunite Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. But after many years of conflict, it was rethinking its commitment to violence. Weary of fighting, many in the group began seeking a way to enter politics and pursue their objectives by working within the system.

The IRA declared a cease-fire in 1994, and pro-British paramilitaries followed. Then, with the help of the British and Irish governments, peace talks began.

Some conflicts are so prolonged and bitter that peace talks require international support—the idea is that third-party negotiators have a better shot at getting sworn enemies to a middle ground. In the case of the Troubles, U.S. Senator George Mitchell played that role. The resulting peace accord, the Good Friday Agreement, was signed on April 10, 1998.

The peace agreement created the blueprint for Northern Ireland to set up its own government with authority over certain issues such as health and education. The government also required power-sharing between pro-British and pro-Irish parties. The Good Friday Agreement l included plans for the disarmament of Northern Ireland’s paramilitary groups, which counted tens of thousands of members at their peak. The violence that had terrorized the region for nearly thirty years had mostly come to an end.

What happened after the Troubles ended?

The end of the Troubles did not mean Northern Ireland suddenly became a peaceful, integrated society. Instead, the region faced the daunting challenges many postconflict societies do. These obstacles include the issue of confronting old fault lines and finding solutions to new problems that sprouted from conflict. In Northern Ireland, those challenges include the following:

Continuing Division: After the Good Friday Agreement, the cycle of tit-for-tat attacks by paramilitary groups ended. But that progress has not led to full integration between Northern Ireland’s divided communities. Instead, many Catholics and Protestants continue to live segregated from each other. Catholics and Protestant communities are sometimes physically separated by a barrier. Northern Ireland has more peace walls today than during the Troubles.

Meanwhile, communities continue to clash over political and cultural issues. These include parades commemorating Protestant history, controversial memorials for individuals linked to violence, and the flying of flags like the Irish tricolor and the Union Jack. Although integration has improved by some measures, recent community surveys show that fewer people believe that Catholic and Protestant relations are getting better; divisions that are likely perpetuated due in part to the bitter political divide between pro-British and pro-Irish parties in the region’s government.

Political Gridlock: In Northern Ireland, identity largely determines not just your neighborhood, school, and friends but also the political party you support. Large numbers of Protestants vote pro-British (unionist); and Catholics vote pro-Irish (nationalist). Politicians play to those groups for votes, which creates political gridlock and hinders the government’s ability to solve critical problems. In 2017, for example, Northern Ireland’s opposing parties refused to compromise on several issues, resulting in the government’s collapse. That breakdown put off plans to revamp Northern Ireland’s struggling health-care system.

Continuing Violence: Though the Good Friday Agreement committed forces to lay down their weapons, paramilitaries did not vanish altogether. Much like during the Troubles, those groups claim they are defending their communities. But instead of squaring off against rival paramilitaries, they are increasingly turning inward on their own communities. Traditional paramilitaries have shifted towards vigilante police [PDF] and carrying out shootings and beatings of those suspected of crimes like selling drugs. At the same time, many paramilitaries themselves are accused of dealing.

Justice and Reconciliation: The Troubles left Northern Ireland with the difficult problem of healing a divided society. For many, the past remains an open wound. In 2011, researchers found the region has the world’s highest recorded rate of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nearly half of adults know someone who was injured or died in the Troubles. And more than three thousand murders related to the conflict are still unsolved. Over the years, Northern Ireland has pursued several different strategies to address its difficult past, including the establishment of a historical deaths investigation unit. Some citizens have advocated for a truth and reconciliation commission. This tool has been used in postconflict situations like South Africa after apartheid to investigate past abuses and help communities gain closure. Northern Ireland has yet to create such a commission, and many residents criticize the government for not doing more to heal the divided society.

Is there still trouble in Northern Ireland?

The challenges Northern Ireland faces in the aftermath of its conflict are not unusual. Post conflict societies often struggle with weak governments and divided populations. Fragile institutions and bitter hostility among communities present the risk that conflict will reignite. Some conflicts do not ever completely cool down to peace but stay at a simmer, with the ever-present threat they will boil over into violence. More than half [PDF] of civil conflicts from the early 2000s restarted within five years. Civil conflicts resolved through negotiations (rather than military victories) are the likeliest to begin again.

Despite those daunting statistics, Northern Ireland remains more or less peaceful today. But a reminder of how fragile that peace still feels was on display in 2016 when the United Kingdom decided to leave the European Union in a referendum known as the Brexit vote.

Most voters in Northern Ireland voted against Brexit. Many feared its effects on the border with the Republic of Ireland. During the Troubles, border checkpoints were the sites of repeated violence. However, following the Good Friday Agreement, the border essentially disappeared. Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland were both in the European Union and the same customs zone.

With Brexit, many people worried that a stricter border could return. Experts predicted that if a so-called hard border separated the two regions, people would protest and physically destroy border infrastructure—a situation that could contribute to a resurgence in fighting.

On January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom left the European Union. Politicians avoided a full-scale crisis in Northern Ireland by creating a plan for the region to continue following EU customs rules and to keep its invisible border with the Republic of Ireland—though details could still change. Nevertheless, the Brexit vote revealed the undercurrent of fear still present in Northern Ireland over a return to its troubled past. This saga highlighted the fact that ending conflict and ensuring lasting peace remain separate and complex challenges.