Understanding the Constructive and Destructive Natures of Nationalism

Nationalism can unify diverse societies. But when taken to extremes, it can also fuel violence, division, and global disorder.

Teaching Resources—Building Blocks: Introduction (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

Countries are the building blocks of the modern world. Nearly two hundred make up the globe today. They vary in population and size: China and India are home to more than one billion people. Meanwhile, Vatican City and Monaco are smaller than a single square mile.

The world also comprises a large number of nations.

While the terms country and nation are often used interchangeably, they have subtle, but important, differences. Nations are groups of people united by ethnic, linguistic, geographic, or other common characteristics. Countries, on the other hand, refer to places with governments that are internationally recognized and have the power to oversee what happens within their borders.

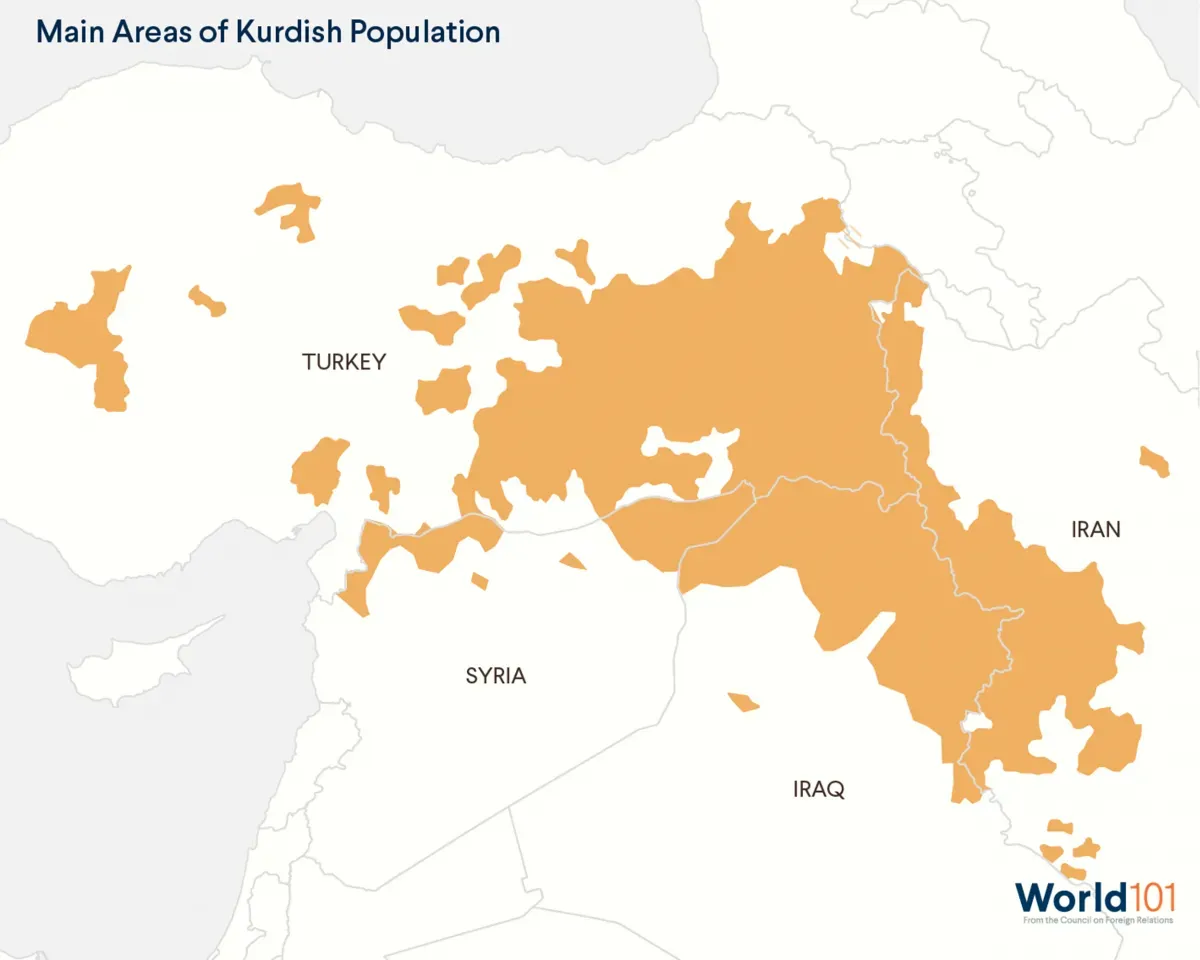

Like countries, nations come in different shapes and sizes. But unlike countries, nations are not always reflected in borders on a map. Some nations span multiple countries, such as the Kurdish nation, whose approximately thirty million people live in Armenia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. The Kurds, importantly, do not have a country of their own and are a minority in all the countries that they inhabit.

Other nations exist primarily within one country. Belgium, for example, is largely made up of two different groups of people—the Flemings and Walloons—which have distinct languages and cultural identities. Few members of these two nations live outside Belgium. Sometimes, a nation neatly overlaps with the borders of a country. For example, in Japan, 98 percent of citizens are of the same ethnicity and nearly all speak Japanese and share national traditions.

Groups of people working to advance the interests of their nation, country, or would-be country is known as nationalism. Often, nationalism is invoked by groups pushing for independence, especially when they are ruled by perceived outsiders. But nationalism doesn’t always mean being pro-independence. It can also entail people promoting their culture, asserting their religious beliefs, or organizing for greater political power.

In certain contexts, nationalism can serve as a basis for unity, inclusion, and social cohesion for a country. But when taken to extremes, nationalism can fuel violence, division, and global disorder.

When is nationalism positive?

Rarely do all people in a country look, speak, and pray the same way. Even in Japan—one of the world’s most homogeneous societies—more than two million citizens are ethnic minorities.

In reality, most countries comprise a diverse tapestry of unique identities. When that’s the case, how do countries create a common national identity amid so many internal differences? Let’s take a look at Indonesia.

The sprawling southeast Asian archipelago has around six thousand inhabited islands. It’s the world’s fourth most populous country. Indonesia has more than 260 million citizens who speak over seven hundred languages and practice a half dozen official religions. Its existence today as one country is the result of three centuries of colonization, during which mostly European empires drew borders. These colonial boundaries had little regard for any national, economic, or internal political criteria.

So how has Indonesia stuck together since gaining independence, and what does it now mean to be Indonesian?

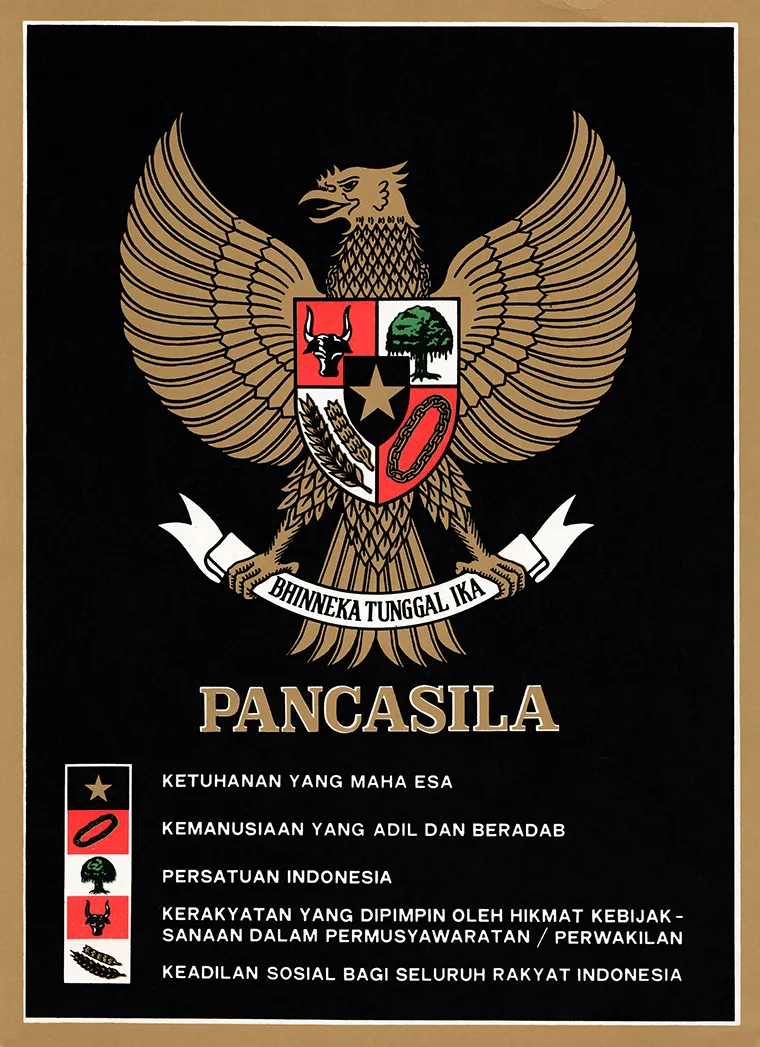

Rather than build a national identity based on geography, language, religion, or ethnicity, Indonesia’s founding father, Sukarno, forged one through ideas. In 1945, just weeks before his country achieved independence, Sukarno laid out a vision known as Pancasila—meaning Five Principles—for an Indonesian identity. This philosophy was intended to unite the diverse and soon-to-be independent country. An iteration of Sukarno’s Pancasila would ultimately appear in the preamble of the country’s constitution. To be Indonesian meant adhering to the following:

- belief in the One and Only God

- just and civilized humanity

- the unity of Indonesia

- democratic rule that is guided by the strength of wisdom resulting from deliberation/representation

- social justice for all the people of Indonesia

Pancasila is an example of how a belief in shared ideas and values can unify diverse groups of people. It encourages social cohesion and contributes to pride in one’s country, often referred to as patriotism. Moreover, national identities built solely around characteristics like ethnicity, language, or religion exclude those who do not meet these narrow criteria. As a result, a national identity based on ideas (as well as shared history and common experience) is more accepting.

Throughout the world, liberal countries build unity around common ideas such as freedom and equality. Like Pancasila, liberal principles are often enshrined in countries’ laws and constitutions.

But just because a country lays out a vision for one, all-inclusive national identity doesn’t mean that its citizens are always treated equally. In Indonesia, people have been imprisoned for not adhering to one of the country’s six official religions. And in the United States—a country that prides itself on its diversity—discrimination is still a major issue. This issue was especially evident during the countrywide protests for social justice and against police violence targeting Black Americans following the death of George Floyd.

When is nationalism negative?

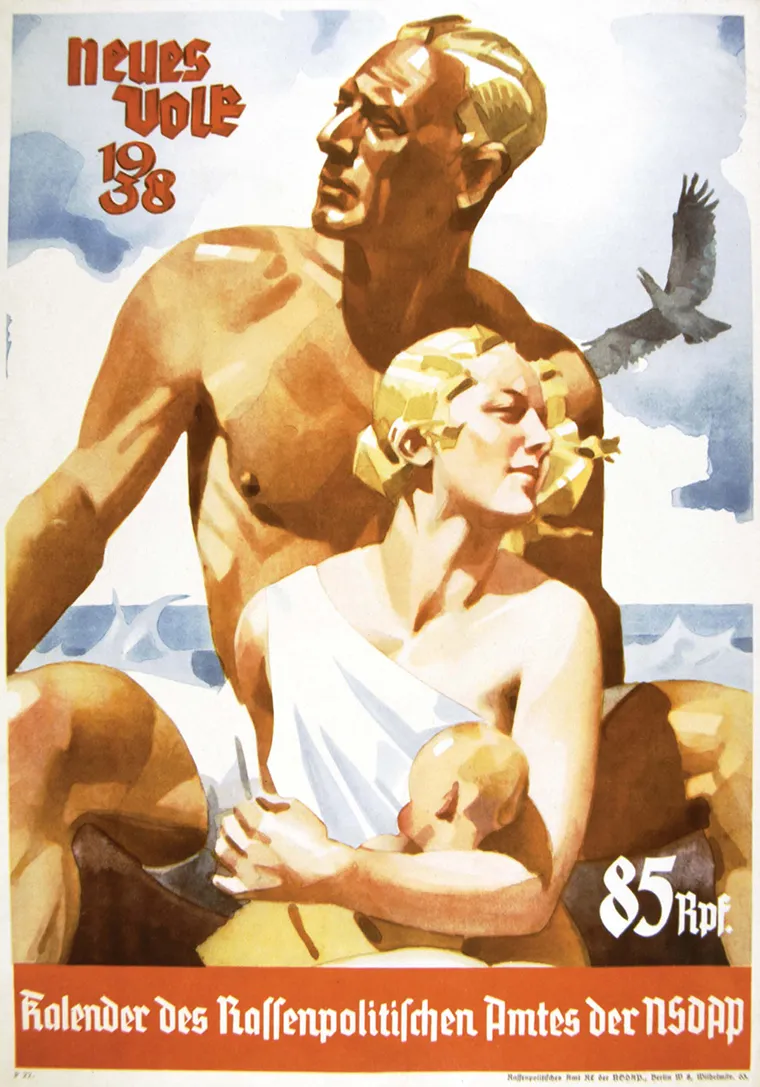

Like ideologies or technology, nationalism can be a positive or a negative force. Narrow or aggressive forms of nationalism can be highly divisive. Such nationalism calls for advancing the interests of one group above all else—even at the expense of others. Extreme nationalism is illiberal and intolerant. It doesn’t accept those outside the narrowly defined nation as equal. This “us versus them” mentality, often rooted in ideas of racial and national superiority, can lead to dangerous and violent ends.

What are some instances in which nationalism fuels conflict and global disorder?

Extreme nationalism (hyper-patriotism): Aggressively advancing one country’s or nation’s interests can have consequences that reverberate around the world.

Such strident nationalism precipitated World War I. Shortly thereafter, the world witnessed perhaps the most dramatic example of extreme nationalism fueling global disorder: Nazi Germany. There, a belief in Aryan (essentially white Germanic) racial superiority—a manifestation of what is known as ethnocentric nationalism—led to World War II. Extreme Nationalism unleashed the deadliest conflict in human history, which included horrific campaigns of identity-based violence. Particularly, the Nazi government perpetrated the Holocaust, a systematic killing of over six million Jews.

Since the end of World War II, European leaders have sought to promote regional security and prosperity over solely national interests by binding countries together through political and economic institutions like the European Union (EU). But recently, a rising tide of nationalism has led countries to once again question such partnerships. Most notably, nationalism fueled the United Kingdom’s decision in 2016, known as Brexit, to leave the EU.

Elsewhere in Europe, identity and exclusive nationalism have led to an aggressive foreign policy that threatens world order. For instance, the Russian government has pursued a multi-year campaign to occupy land in the neighboring nation of Ukraine, partially under claims about its support for ethnic Russians living in the country. However, such justifications are undermined by at least one poll showing that the majority of ethnic Russians in Ukraine oppose Russia's land grab.

Exclusive nationalism: This is the idea that only people who meet certain criteria are citizens and those who are not part of this group can never be equal. In Saudi Arabia, for instance, Islam is the official religion, and non-Muslims cannot become citizens. Even then, not all Saudi Muslims are treated equally. In the majority-Sunni society, adherents of Shia and other minority denominations face prejudice.

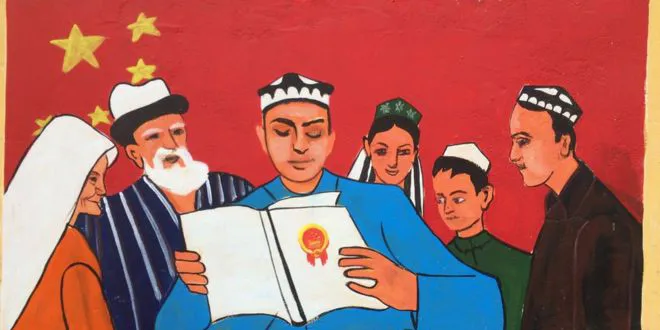

Strict definitions of who is and is not part of the nation can lead to economic and political discrimination or even violence as governments attempt to forcibly assimilate minority groups.

In China, the government has forced over one million Uighur Muslims into detention centers, where detainees are made to learn Mandarin, renounce Islam, and pledge loyalty to the Chinese government.

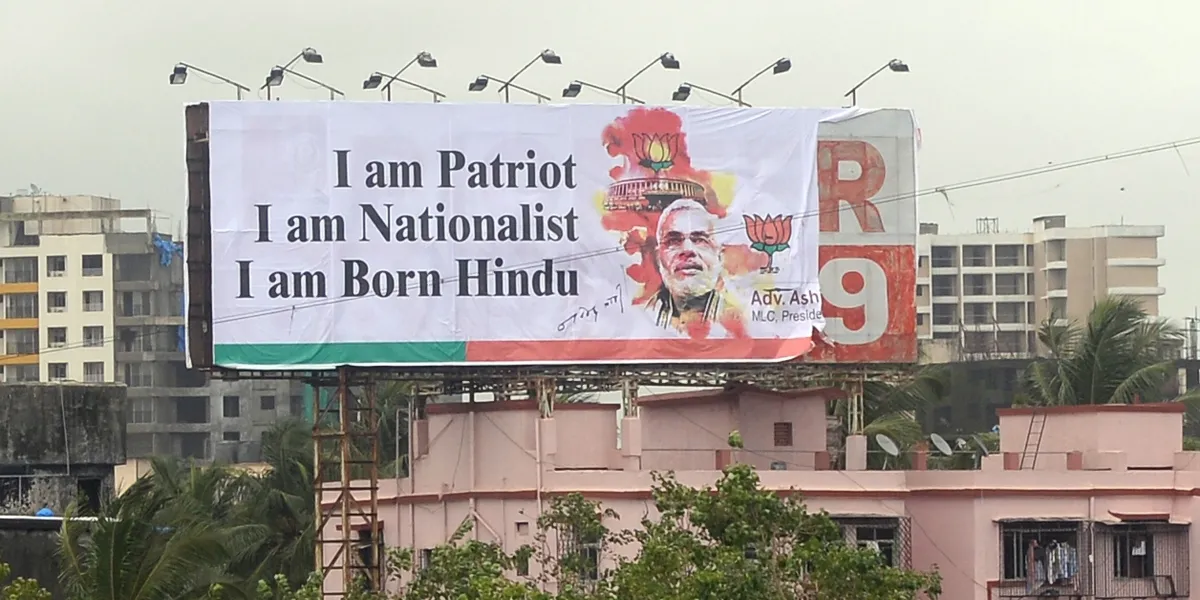

In Iran, minorities often face government persecution; for instance, Baha’is—adherents of a small religious group—are barred from attending universities. In India, Hindu nationalists, who have gained power in recent years, reject the country’s founding vision as a secular, multicultural society. They have increasingly advocated for preferential treatment for Hindus. At this times this has come at the expense of the rights of some two hundred million Muslim Indians.

In the most extreme cases, nationalism has led to genocide, the targeted mass killing of a specific group of people. In the predominantly Buddhist Myanmar, Muslim Rohingya have faced decades of persecution. Tensions spiked in 2017 when the government carried out a violent and brutal campaign against the ethnic Muslim minority. This violence forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee into neighboring Bangladesh.

Economic nationalism: This form of nationalism promotes domestic control of the economy, usually to protect jobs and minimize imports. Economic nationalists also tend to oppose free international trade. To shore up local industries against foreign competition, governments often implement protectionist policies, including tariffs, subsidies, and import quotas.

On the surface, a policy that purports to put the nation’s economic interests first seems fine. However, such policies can actually hurt that country’s citizens. Tariffs increase the prices of imported goods, and consumers must bear the additional cost if the goods are not produced domestically. When one country imposes tariffs on goods from another, it usually faces retaliatory tariffs. These tariffs make it difficult for industries to sell their products at competitive prices abroad.

In today’s global era, international trade is essential. No country is entirely self-sufficient—it cannot rely solely on what it produces within its borders. Whether it’s importing fuel, food, electronics, or face masks during a pandemic, a country needs international trade to function. Some experts even argue that increased trading makes the world a safer place, as countries that are economically interdependent are less likely to go to war.

Nationalism in a Global Era

At the end of World War II, countries sought ways to ensure the world would never again break down into such horrific conflict. Leaders created new global institutions—including the United Nations, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. These governing bodies form the backbone of what is called the liberal world order. For decades, this liberal world order has tried to guard against the most violent impulses of nationalism. They create forums for international cooperation designed to promote collective security and economic growth. And while certainly not always successful, it has contributed to a largely peaceful and prosperous era for many.

But around the world, nationalism is on the rise again, often along with populism—the movement when large groups of people believe the ruling elites are not addressing their concerns. This combination of sentiments has led to the emergence of new leaders who claim to represent “the people,” alongside efforts to oust existing elites.

Numerous factors account for these developments, including stagnating wages, rising income inequality, and job losses. While such losses in the labor market are mostly associated with technological innovation, they are often attributed to global factors, such as the 2008 global financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic. This is also happening—somewhat paradoxically—as the world grows increasingly interconnected: globalization has enabled people, ideas, money, goods, data, drugs, weapons, greenhouse gasses, viruses, and more to move around the world at unprecedented speeds.

In a time when so much travels across borders so quickly—including today’s greatest threats—the world requires more cooperation. No country can deal successfully with global challenges on its own; countries fare better when they join forces with like-minded partners.