The European Union: The World’s Biggest Sovereignty Experiment

Countries fight to protect their sovereignty. So why would they willingly give it up?

In the summer of 2016, bright red buses drove around the United Kingdom (UK), bearing a four-word slogan: “Let’s take back control.”

The message aimed to rally support for the UK to leave the European Union (EU). Control, to the “Leave” campaign, meant the power to manage Britain’s borders, health-care spending, and defense. Put simply, the slogan urged a restoration of sovereignty. The “Leave” campaign worked: to the surprise of many, the UK narrowly voted for a so-called Brexit.

The Value of Sovereignty—and of Giving It Up

Sovereignty is considered to be a country’s fundamental principle. It means that countries get to control what happens within their borders. Sovereignty also establishes the norm that countries can’t interfere in other countries’ domestic affairs. When a country is recognized as sovereign, it can create its own laws and political infrastructure. A sovereign nation also has the power to develop education and health-care systems, and religious and social norms.

In theory, sovereignty provides countries with an equal playing field. The doctrine is designed to protect countries from being invaded or controlled by other, stronger ones.

While the concept is clear in the abstract, sovereignty in practice has never been respected quite so cleanly: countries violate each other’s sovereignty all the time, as illustrated in this module.

But, less intuitively, countries also voluntarily give up a certain degree of their sovereignty. This occurs when countries enter into international treaties and join international organizations. Countries that engage in multilateral organizations agree to forfeit their right to set their own rules and instead delegate specific powers to those bodies in return for the benefits of international cooperation. In international rulemaking organizations, like the United Nations or the World Trade Organization (WTO), countries are not always the ultimate decision-makers. They have agreed that, in certain cases, international rules on trade, the use of force, arms control, or human rights will dictate (or at least guide) their actions.

Ceding a measure of sovereignty has precedent. But no organization has gone as far as the EU. The EU is a collection of European countries that have pooled their sovereignty to a great extent and handed certain powers over to a supranational authority. The EU represents an unparalleled experiment in balancing national and collective interests.

A Brief History of European Integration

After World War II, global powers created multiple organizations. The goal was to prevent another devastating conflict. These institutions and agreements included the United Nations, to create a peaceful form for dialogue and reduce the risk of war; the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (which later became the WTO), to promote international trade by creating clear trade rules; and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to ensure international financial and monetary stability.

Attempts at international cooperation had failed in the past: after World War I, the League of Nations (forerunner to the United Nations) fizzled out. The failure of the League of Nations was in part because the United States, wary of foreign entanglements, refused to join. One world war later, leaders knew that for these efforts to work—to have legitimacy and authority—countries would have to grant these bodies certain powers. However, to do so, countries were required to give up some of their sovereignty in exchange for the prospect of stability and collective security. If the WTO concludes that a country violated trade rules, the infraction can result in fines. And if the United Nations believes a country is flouting international law, the Security Council can impose sanctions or even authorize the use of military force.

However, Europe, the place of origin of both world wars, took the idea of international cooperation a step further. Countries decided to pool their sovereignty within a regional body with supranational characteristics. A European project, one that would bind countries in a political and economic union, was put in motion shortly after World War II. The goal was to ensure lasting peace in the region—especially between France and Germany, whose rivalry was central to both world wars.

In the early 1950s, European leaders regarded strong national interests with suspicion. The French diplomat Jean Monnet, who is considered the architect of European integration, believed his approach—building European interdependence—was the way to reconstruct the continent. Rather than promoting French interests or German interests, he advocated advancing a European agenda that would allow the continent at last to transcend the bloody rivalries that yielded such destruction. Central to his thinking was to link the economies of Germany and France. As a result, war between them would become unthinkable.

In his vision, a supranational body would craft laws for the benefit of all European countries. This model is similar to how the U.S. government creates laws that are supposed to be for the good of all its states. The more policies European countries coordinated, the more each member would come to depend on the success of its neighbors, and the stronger, and safer, Europe would be. Monnet envisioned a United States of Europe, much like the United States of America.

This increase in coordination is sometimes described as the bicycle theory of European integration. Just as a cyclist requires momentum, so too would Europe rely on ever-closer cooperation to propel it. Without cooperation, the whole endeavor could topple.

However, this model had its detractors. Most notably, French President Charles de Gaulle rejected the idea of an eventual European—rather than French—identity and agenda. Instead, de Gaulle’s view of a “United Europe of States” maintained strong national identities and distinct national governments. De Gaulle succeeded in imposing some limits on the organization’s power. For example, the EU required unanimous votes on several decisions. This requirement prevented the complete cession of sovereignty to the supranational body. As a result, the EU does not always have the final say over the objections of any one member country.

The first incarnation of this European project, born in 1951, was limited geographically to just six countries. Administratively, the union existed to merely remove trade barriers in the coal and steel industries. However, while it teetered at times, European integration did pedal forward. The organization that morphed into the EU added member countries as its mission expanded over the decades. In 1992, it officially began laying the groundwork for a single currency (the euro). The adoption of the euro would require the EU to coordinate more closely than ever.

But debates still rage over the direction of European integration—what’s called sovereignty-sharing or, in reality, sovereignty-ceding. Some European leaders decry the EU’s overreach on their national affairs while others lament the EU’s limited ability to hold members accountable. Issues of accountability persist on issues such as budget deficits and undemocratic domestic legislation.

What Is the EU Today?

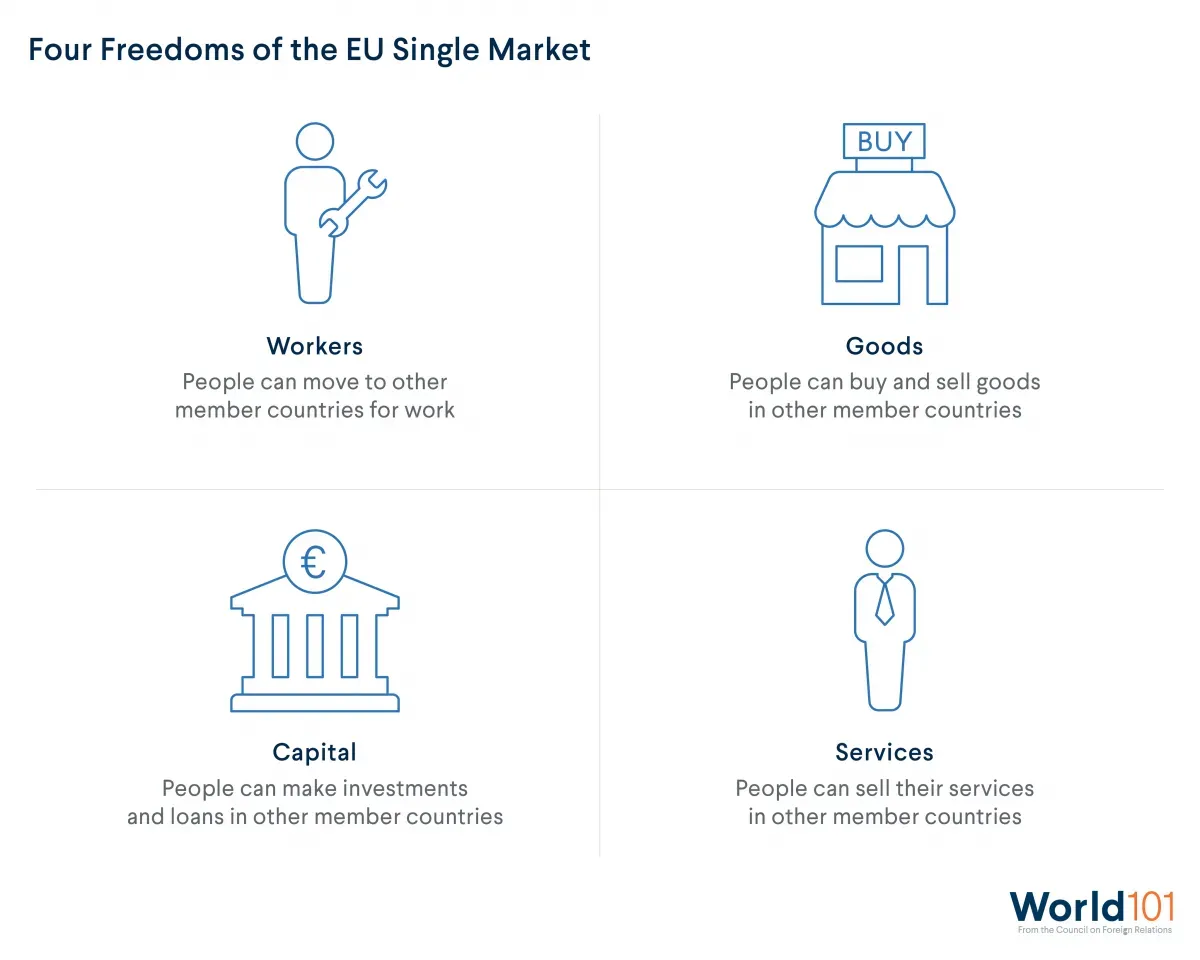

As of 2020, the EU has twenty-seven member countries. The organization works to ensure that workers, goods, capital, and services can move freely within its borders. These are known as the four freedoms.

The EU operates a single market (an economic zone designed to function with one set of regulations and no internal trade barriers). The EU also controls a visa-free area called the Schengen zone. Additionally, the modern European project coordinates labor laws to make working in other countries relatively seamless. Finally, the EU negotiates trade deals as a bloc, giving European countries more leverage when working with bigger economies.

In practical terms, the EU allows a German citizen to commute to work in the Netherlands. The EU also enables goods to travel over country borders as if they were moving inside a country. A train ride from Vienna to Paris requires no passport or currency exchange. Products developed in Estonia adhere to the same rules as those developed in Spain, and an Estonian company can easily sell in Spanish stores.

To govern all of this activity, the EU operates institutions that have varying jurisdiction over certain policy areas. Monetary policy, trade, and fishing, for example, are exclusively under the control of the EU. The European Court of Justice sets precedent for national judicial systems. Decisions over defense and security are shared between the EU and national governments. For example, the EU has collectively imposed sanctions on Russia in response to Russian aggression in Ukraine. Meanwhile in health care, education, and tourism, the EU merely supports national governments through funding or by setting guidelines.

What Do EU Members Get Out of This Arrangement?

EU member countries contribute to the EU budget, comply with EU laws, and vote to elect officials to its institutions. Why cede—or, to use the EU’s term, “pool”—sovereignty in this way? By cooperating closely and establishing some supranational policies, countries in the EU enjoy economic, political, and security benefits.

Economic benefits

Goods and services are cheaper when border controls are eliminated, trade barriers are lifted, and only one set of regulations must be met. A 2019 study found that the average EU citizen is 840 euros richer per year as a result of the single market. Nineteen countries in the EU use a single currency, the euro, which encourages tourism. It also makes it cheaper for poorer countries to borrow money, as they need not worry about exchange rate fluctuations.

From a financial perspective, EU membership particularly benefits poorer countries. Here the EU provides significant funding for public investment projects, including those that improve childcare options, increase internet access, and create jobs. Across the continent, the EU also provides agricultural subsidies, amounting to approximately $65 billion each year, that keep many European farmers afloat.

Political benefits

EU countries gain political leverage by banding together. As the second-largest economy in the world, the EU negotiates better trade deals than a European country could if it were acting alone.

In doing so, the EU helps create global standards. Countries that want to enter into trade deals with the valuable bloc often have to abide by strict regulations on data privacy, emissions standards, and human rights.

Security benefits

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), another post–World War II initiative, binds the United States, Canada, and much of Europe in the world’s largest security alliance. But a defense agreement is also baked into EU membership: members are required to provide aid and assistance when another member asks. However, security commitments are not required for countries with long-standing traditions of neutrality. Ireland or Sweden, for example, can get exemptions from defense arrangements. The EU has entered into a debate over whether it should continue to rely on the United States for its security. The alternative is that the EU becomes more self-dependent—a concept referred to as strategic autonomy.

Many smaller countries with unfriendly neighbors have rallied for ramped-up EU defense efforts. For instance, the EU introduced a military mobility initiative that allowed the union to quickly move troops and equipment across Europe to protect eastern European countries from Russian invasion. This initiative was adopted following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Drawbacks of Ceding Sovereignty

Despite its collective benefits, power-sharing can be a divisive endeavor. The 2016 Brexit vote made this clear. Several countries in Europe, such as Norway and Switzerland, have chosen not to join the EU (though they have coordinated in some policy areas, such as trade and travel). Some existing members, like Hungary, are deeply critical of it. The downsides affect member countries differently.

Hazards of Economic Interdependence

With economic benefits come risks. The nineteen countries that use the euro are bound to the same monetary rules. However, such close economic integration does not mean those nineteen national governments have the same political priorities. Such conditions have made it difficult for the EU to create rules that work well for all economies.

It also means that one tanking economy can bring down the entire union. An economic crisis in one country can certainly amplify the effects of an economic downturn in another. In 2010, this scenario played out in the so-called eurozone crisis, when Greece’s cratering economy threatened the economic stability of much of the EU.

When One Country Becomes Too Powerful

Certain countries will always be more powerful than others, but sovereignty is supposed to be an equalizer. It prevents strong countries from changing the borders of their weak neighbors or meddling in their domestic politics and law (with specific exceptions).

In the EU, countries cede some of the powers that sovereignty is designed to protect—national budget–making, monetary policy, and immigration and work authorization laws. Countries do so to reap the benefits discussed above and because they trust that the EU will use those powers to serve the interests of all members. But when one EU country exerts too much influence, it can set the bloc’s agenda to serve its own national interest more than that of the collective.

Germany, the EU’s richest and most populous country, is considered to be the bloc’s most influential member; its longtime leader Angela Merkel is sometimes referred to as the chancellor of Europe. In 2015, more than one million migrants entered Europe, the largest influx of people since World War II. During this migration crisis, Germany agreed to take in thousands of refugees and expected that other EU countries would do so as well. When some refused, Germany enlisted the EU to introduce quotas to force countries to accept refugees. This demand was eventually dropped after years of EU deadlock on migration issues. Countries like Hungary accused Germany of attempting to impose its national policies upon the entire bloc, undermining the collective interests of the EU.

When Sovereignty-Sharing and National Identity Struggle to Coexist

In addition to its simple, primal slogan, the red Brexit bus advertised an eyebrow-raising claim: “We send the EU £350 million a week,” it read. “Let’s fund the NHS,” referring to the UK’s widely beloved health-care system.

Fact-checkers later debunked the £350 million claim. However, that didn’t stop people from accepting that figure as true. It was an easy sell because the claim fit with their belief that EU membership came at the expense of domestic programs—and national identity.

To some critics, Brussels, where the executive branch of the EU is headquartered, evokes a nanny state—an overbearing authority that encroaches on sovereignty. Some still cling to the pervasive myths—essentially misinterpretations—like the EU forces Italians to make mozzarella from powdered milk or that it nitpicked on the name of a British snack mix. These complaints, though trivial, reflect larger questions about the balance of power between the EU and national governments.

In the 1950s, fiercely protecting national sovereignty was often considered distasteful compared to achieving regional peace. But recently this balance has undergone intense scrutiny. In the last several years, some politicians have gained traction—and votes—across Europe by pitting people against the EU elite. These messages have resonated in countries like Greece, where people mobilized against the EU’s demands to balance its budget; in Hungary, where leaders have rejected the EU’s migration quotas; and in Poland, where the far-right government has dismissed EU criticism of the country’s crackdown on the independence of its courts.

Where Is the EU Headed?

The EU’s challenges are far from settled. Some are old: grouping countries with different financial, cultural, and geographic realities has inherent difficulties. Others are new: the UK’s exit dealt a harsh blow to the bloc. Some experts feared the departure—the first in EU history—would make the institution seem like a hotel that countries could check in or out of at will. But the fact that the UK’s departure took years of difficult negotiations (and agreements on post-Brexit trade and travel relations have yet to be made) has also revealed just how interconnected Europe has become. Amid the coronavirus crisis, the EU announced a $2 trillion stimulus plan to help the region’s economies recover. With the support of powerful members, including Germany and France, the massive package proved to knit the EU together even more tightly.

The EU stands alone as a sovereignty-pooling organization. No other region in the world operates such an ambitious endeavor. Indeed, while some international organizations have been unable to evolve as the world changes (e.g., the WTO has not agreed on comprehensive new trade rules since 1995), the EU has forged ahead, adding members and continuing to mostly deliver on its original promise: an enduring peace on the continent.