How Does History Inform the Chinese Communist Party’s Domestic and Foreign Policy Goals?

Learn how China’s transformation from a state of economic and political collapse to its rise as a global power shapes the motivations of its leaders today.

At the climax of Wolf Warrior II, the highest-grossing movie in Chinese history, the 2017 film’s Rambo-style hero, Leng Feng, faces off against an American mercenary named Big Daddy. “People like you will always be inferior to people like me,” Big Daddy says, holding Leng Feng at knifepoint. But in a flash, Leng Feng violently overpowers the American. “That’s history,” says the Chinese fighter.

Wolf Warrior II smashed box office records in China for a reason. The story of a down-and-out soldier fighting off powerful foreign enemies and restoring China’s honor struck a chord with audiences who saw parallels in China’s recent history. To many of its citizens, China is an underdog, a once-great nation brought low by nineteenth- and twentieth-century invasions, internal rebellions, civil war, and international isolation. Only recently has China become strong enough to retake its place among the world’s leading economic and political powers.

This narrative has been embraced and perpetuated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the political party that founded the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. The CCP continues to hold a tight grip on power to this day. The party claims it alone can keep predatory foreign forces at bay, maintain internal unity and stability, and restore China’s great power status after decades of conflict and poverty. By referencing low points in the country’s modern history when China was invaded and divided, the CCP seeks to promote a narrative that, without strong leadership, the country is taken advantage of. This historical argument thereby legitimizes the party’s authoritarian rule and present-day domestic and foreign policies. What’s more, in today’s increasingly interconnected world, those policies have implications not just for China’s 1.4 billion people but also for the global economy, world order, and the state of human rights.

This resource walks through China’s transformation from a state of economic and political collapse to its rise as a global power and explores how that history informs the goals and motivations of Chinese leaders today.

Part One: China’s “Century of Humiliation”

The People’s Republic of China only came into being as a country in 1949. However, Chinese culture and various Chinese political entities go back millennia.

Chinese inventions, including the compass, fireworks, paper, and printing, changed the course of human history. Before Italian explorer Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1492, fifteenth-century admiral Zheng He sailed the Ming dynasty’s massive naval armada from East Asia to East Africa. Meanwhile, thanks to successive dynasties' place at one end of the Silk Road—an ancient global trade network—and ravenous European demand for Chinese goods like silk, tea, and porcelain, China became the world’s largest economy. By 1820, China accounted for nearly one-third of global production.

By the mid-twentieth century, however, China’s economy and political system were in tatters. What went wrong? Let’s explore several events that took place during what many in China have branded its “century of humiliation.”

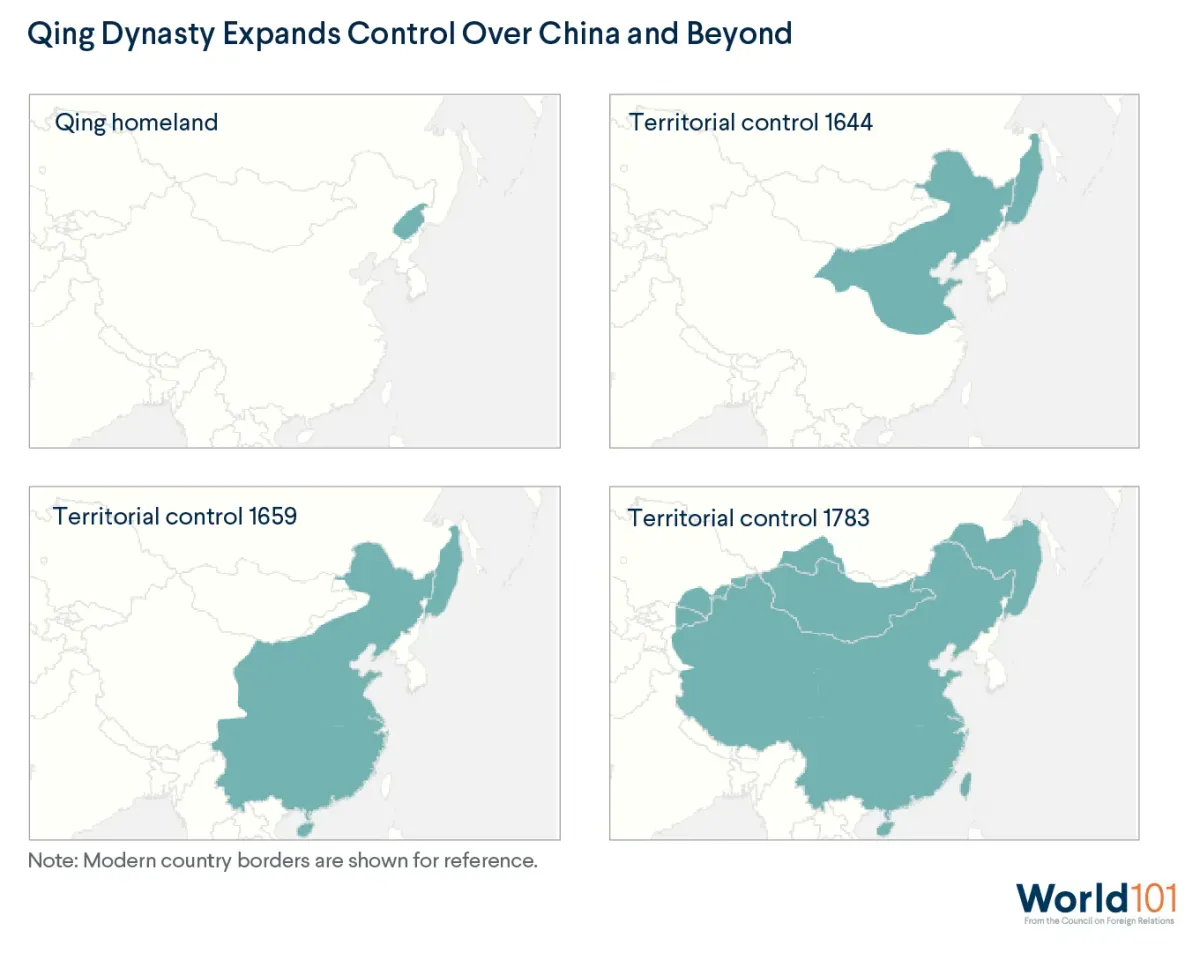

The Qing empire collapses: In the 1790s, the Qing dynasty ruled over much of what is now known as China. Its leaders had doubled the size of China’s previous territory and population to create a stable, wealthy nation. At the height of the Qing dynasty, China was home to more than three hundred million people.

But problems were on the horizon. As the empire’s population grew, ordinary people struggled to feed themselves and millions died in famines. Meanwhile, elites enjoyed the spoils of corruption. As a result, there was little reform of the government and military. Conquered regions on the fringes of the empire stirred restlessly.

Then, in 1839, a decisive conflict set off a series of foreign incursions. The United Kingdom—worried at how fast British silver was flowing out of the country to buy tea and porcelain—had long attempted to entice China to import more of its wares. But the Chinese market wouldn’t bite—that is until the British began selling opium. Concerns in China mounted over rising consumption of the drug and the sudden reversal of trade fortunes. As a result, Chinese officials seized and destroyed twenty thousand chests of opium at the port of Canton (now Guangzhou). The British, eager to force favorable trading conditions with China, now had the fight they were looking for.

Although Chinese forces outnumbered the British ten to one, they were quickly outmaneuvered and outgunned by the British Navy. This loss was not the Qing empire’s last. The First Opium War, as it came to be called, was followed by a second. Further conflicts with Western powers followed. Then, Japan invaded and colonized the Qing dynasty province of Taiwan in 1895. Territory was lost, and foreign powers, including France and Germany, set up shop in ports where they had previously been forbidden from trading. These foreign powers enjoyed extraterritoriality on Chinese soil, meaning their citizens were not subject to Chinese laws—a humiliating blow to the Qing empire.

These incursions weakened the Qing empire and fueled domestic resentment. Anti-government sentiment ultimately erupted in the mid-nineteenth century with internal insurgencies that left between twenty and seventy million people dead.

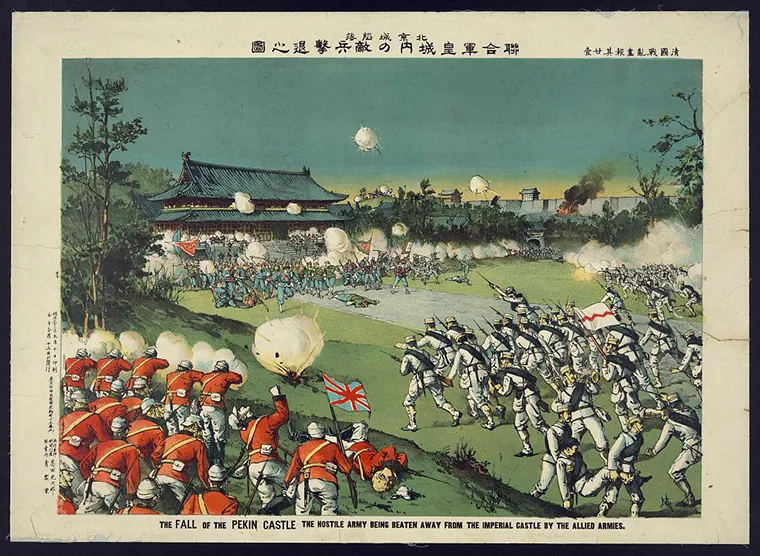

Then, in 1900, Westerners and Chinese Christians became targets of a movement called the Boxer Rebellion, which was suppressed not by the Qing government—which at first encouraged the attacks on foreigners—but by a coalition of foreign countries. After the conflict subsided, those countries demanded 450 million silver taels (equivalent to eighteen thousand tons of silver) in financial damages. The conflict and its resolution revealed the Qing empire’s inability to control affairs within its borders.

Nearly bankrupt, militarily outmatched, and politically unpopular, the centuries-old Qing empire collapsed in 1911. Sadly, darker days were ahead. In the following decades, tens of millions would perish due to famine, poverty, and conflict.

Internal division and Japanese occupation: Soon after the Qing dynasty disintegrated, the former empire splintered into fragments controlled by regional warlords. Amid the political turmoil, two rival factions emerged eager to lead the country: the Nationalist Party, formed in part by anti-Qing revolutionaries, and the Communist Party, which took inspiration from Russia’s 1917 revolution. During the 1920s, the larger Nationalist Party absorbed the small-but-growing Communist Party. This so-called United Front conquered dozens of regional warlords on a campaign known as the Northern Expedition.

The marriage of convenience between the Communists and Nationalists, however, would soon break up. Fearing a Communist power grab, Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek pursued a violent purge of Communist Party members in 1927. As a result, a wider civil war soon followed. In 1934, the Nationalist threat forced the Communists’ Red Army to flee its stronghold in southeastern China on a grueling, six-thousand-mile retreat known as the Long March. Of the one hundred thousand troops who began the journey, only an estimated twenty thousand survived.

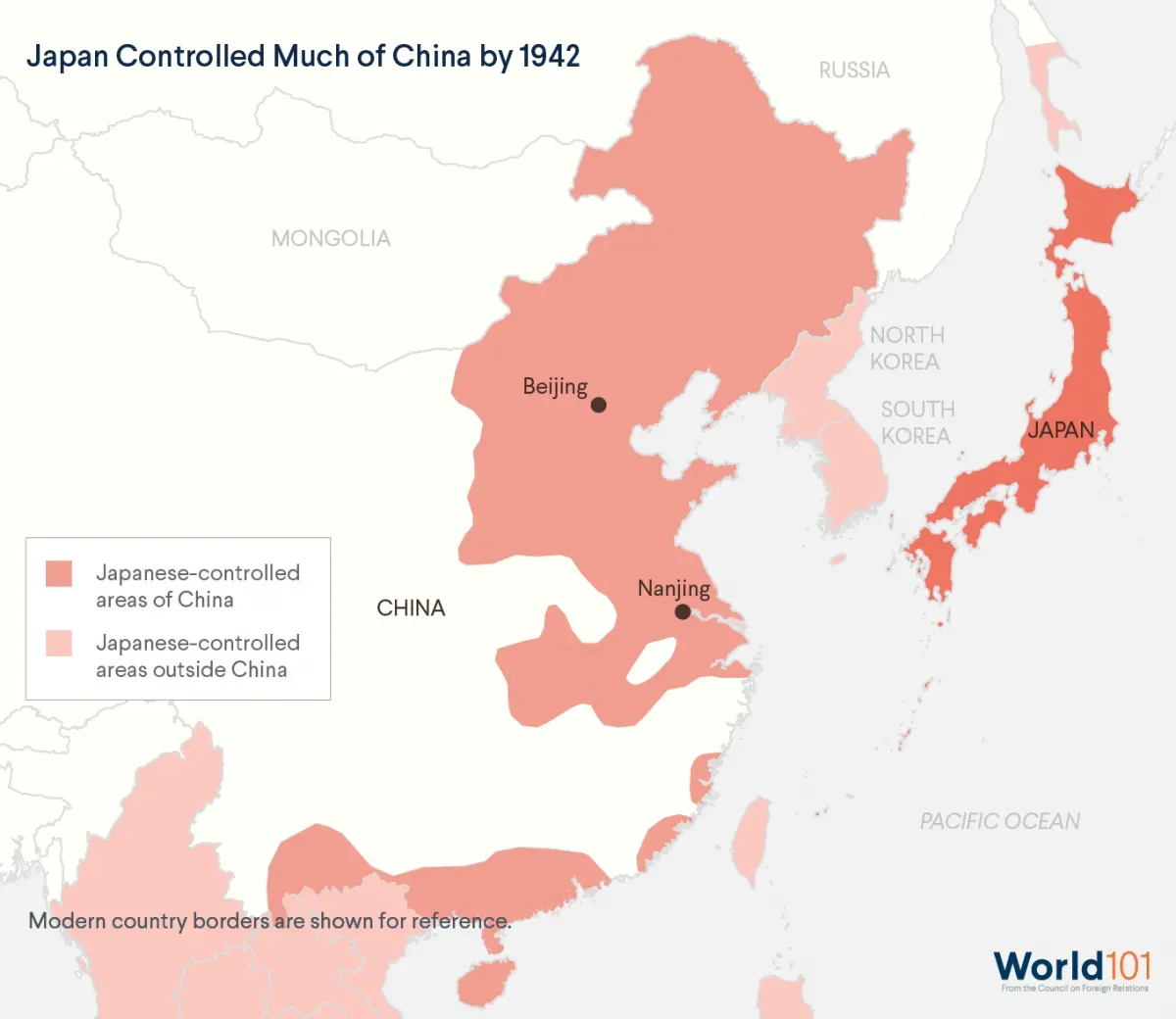

Although this bloody rivalry was far from over, the Nationalists faced another problem: in 1931, Japan invaded Manchuria—a region in northeast China that served as the country’s industrial base. The Communists and Nationalists briefly formed another alliance, but the weakened Communists did not offer the Nationalists much help to repel the invaders. The Japanese would soon control much of China’s eastern seaboard. (By contrast, the Communists took advantage of this time to prepare for a future fight with the Nationalists.) During the conflict, Japanese forces employed brutal tactics—especially during the Nanjing Massacre—including live burials and widespread sexual violence. Between 1937 and 1945, up to twenty million Chinese people are estimated to have been killed. Another ninety million were internally displaced.

Japan only withdrew from China in 1945 after its defeat in World War II. Still, China would not know peace for long. The Communists and Nationalists quickly resumed their civil war, with the Communists eventually prevailing. In 1949, the Communists—led by Chairman Mao Zedong—took control of the government and declared the founding of a new country known as the People’s Republic of China. Meanwhile, the Nationalists fled to the island of Taiwan, which Japan had been forced to forfeit as part of the peace settlement. Despite this loss, the newly formed United Nations and many countries (including the United States) continued to recognize the exiled Nationalists as the legitimate government of China.

Part Two: The Chinese Communist Party in Power

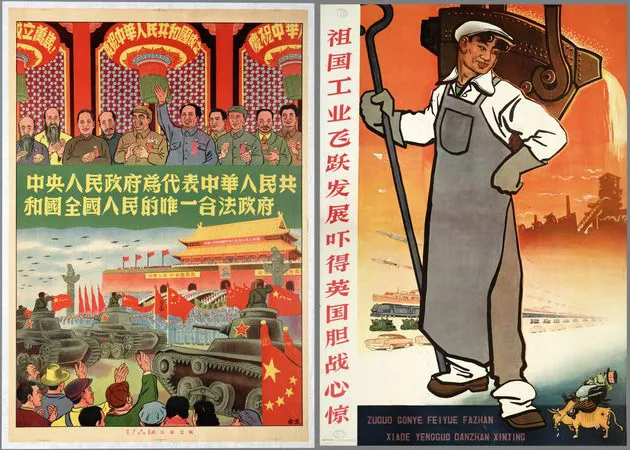

When Mao Zedong and his party took power, China was in a precarious state. A century’s worth of invasions, rebellions, and revolutions had left the country poor, weakened, and humiliated. But Mao had declared an end to China’s shame. “Ours will no longer be a nation subject to insult and humiliation,” he said. “We have stood up.”

Mao aimed to transform his country into a socialist society through nationwide revolution. But in the coming decades, he would launch a series of experiments and political campaigns that would result in some of the darkest periods of China’s modern history.

The Great Leap Forward: Once responsible for nearly one-third of global production in 1820, China accounted for just 5 percent in 1952. Mao, however, believed that with China’s massive population, he could transform the country. He sought to industrialize society almost overnight.”

Mao’s plan, which he named the Great Leap Forward, began in 1958. This economic initiative called for the countryside to produce enough food to fuel industrial growth in the cities and to send abroad for profit. To this end, the CCP organized rural farmers into communes, placed their land under state ownership, and set them to the task of producing grain. Mao also set a goal to double Chinese steel production in just one year. Pressured by CCP officials to meet these targets, ordinary people set up blast furnaces in their backyards to make steel. In response to governmental pressure, Chinese citizens were melting everything from cooking woks to doorknobs.

The results of those initiatives were catastrophic. Backyard furnaces produced unusable steel, and the CCP’s agricultural policies created the worst man-made famine in human history. An estimated forty-five million people perished from starvation and extraordinary violence.

These failures caused Mao’s star to fall in the party, although not for long.

The Cultural Revolution: After the miserable failures of the Great Leap Forward, Mao sought not just to reassert his power but to spur China into political upheaval. He believed repeated revolutions were necessary for socialism to succeed.

Under his guidance, the CCP launched the new Cultural Revolution on May 16, 1966. Mao would achieve his goal of stirring up revolutionary fervor. However, the Cultural Revolution would result in the near dismantlement of the Communist Party from within.

Mao’s new movement called for the proletariat (the workers and peasants of China) to root out and “sweep away all monsters.” This category of enemies included the bourgeoisie (the middle class, academics, and capitalists) as well as anyone perceived as standing in the way of the party and its goals. The movement also urged the creation of a new Chinese identity premised on the destruction of traditional Chinese ways of life. The Four Olds—old culture, old ideas, old customs, and old habits—had to go.

Mao wanted China’s youth to experience revolution so they would carry on the country’s socialist transformation with him at the helm. Millions rose to his challenge. They formed paramilitary groups known as the Red Guards, which wreaked havoc on society. Precious cultural artifacts and religious monuments were ransacked and destroyed. The Red Guards and others targeted teachers, intellectuals, and landlords; anybody they saw as going counter to the revolution was beaten, tortured, and killed. Others were forced to confess to alleged crimes in humiliating public displays.

Meanwhile, the Communist Party was imploding. When Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, he alleged that the party had been infiltrated by counterrevolutionaries and the bourgeoisie. Local operatives responded by overthrowing their superiors.

In 1968, Mao recognized the need to retake control, and the military cracked down. Millions of youths were sent down to the countryside. This was nominally for them to learn from China’s peasant class, but it proved a convenient way to defuse the Red Guards’ power.

The Cultural Revolution only ended in 1976 with Mao’s death. By that point, an estimated three million people had died. Families were torn apart as children denounced their parents for crimes against the CCP. In 1981, the party admitted that the movement caused “the most severe setback and heaviest losses” for the CCP, China, and its people since 1949.

Part Three: The Chinese Dream

Mao Zedong’s leadership resulted in tens of millions of deaths and some of the most brutal violence in modern history. To some Chinese citizens, however, Mao’s unification of the country and his success in restoring its sovereignty stand out as crucial accomplishments. Still, after enduring the catastrophic consequences of Mao’s policies, the country turned toward reform.

Ordinary people across China—reeling from the turbulence of the Cultural Revolution—had begun splitting up collective farmland and taking part in limited private entrepreneurship. Deng Xiaoping, who succeeded Mao’s chosen successor Hua Guofeng in 1978, embraced those moves. Deng instituted further economic reforms that began to integrate China into the global economy. He introduced a period of “reform and opening up,” and eventually, growth skyrocketed. This four-decade trend has helped more than eight hundred million people escape poverty.

Deng would later become known as the architect of modern China. Among his most influential initiatives was the establishment of special economic zones—regions where, unlike during the Mao era, both foreign investment and limited experiments with market forces were encouraged.

Under Deng, limited political reforms also took place. He fostered greater political stability by addressing past CCP mistakes. Deng also undercut the cult of personality that surrounded Mao, famously admitting that Mao was “70 percent right and 30 percent wrong.” When it came to foreign policy, Deng prioritized maintaining external stability so that China could focus on economic growth. He emphasized that China should eschew international leadership, hide its strength, and bide its time. China pursued a positive relationship with the United States and in general did not press its various territorial claims (with a brief war with Vietnam in 1979 standing as the exception).

But the reforms had a limit. That limit was revealed in 1989, after a student-led movement urging democratic changes escalated into hunger strikes and mass demonstrations in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people were killed in the ensuing CCP crackdown ordered by Deng. The message was clear: challenges to the CCP’s rule would not be tolerated.

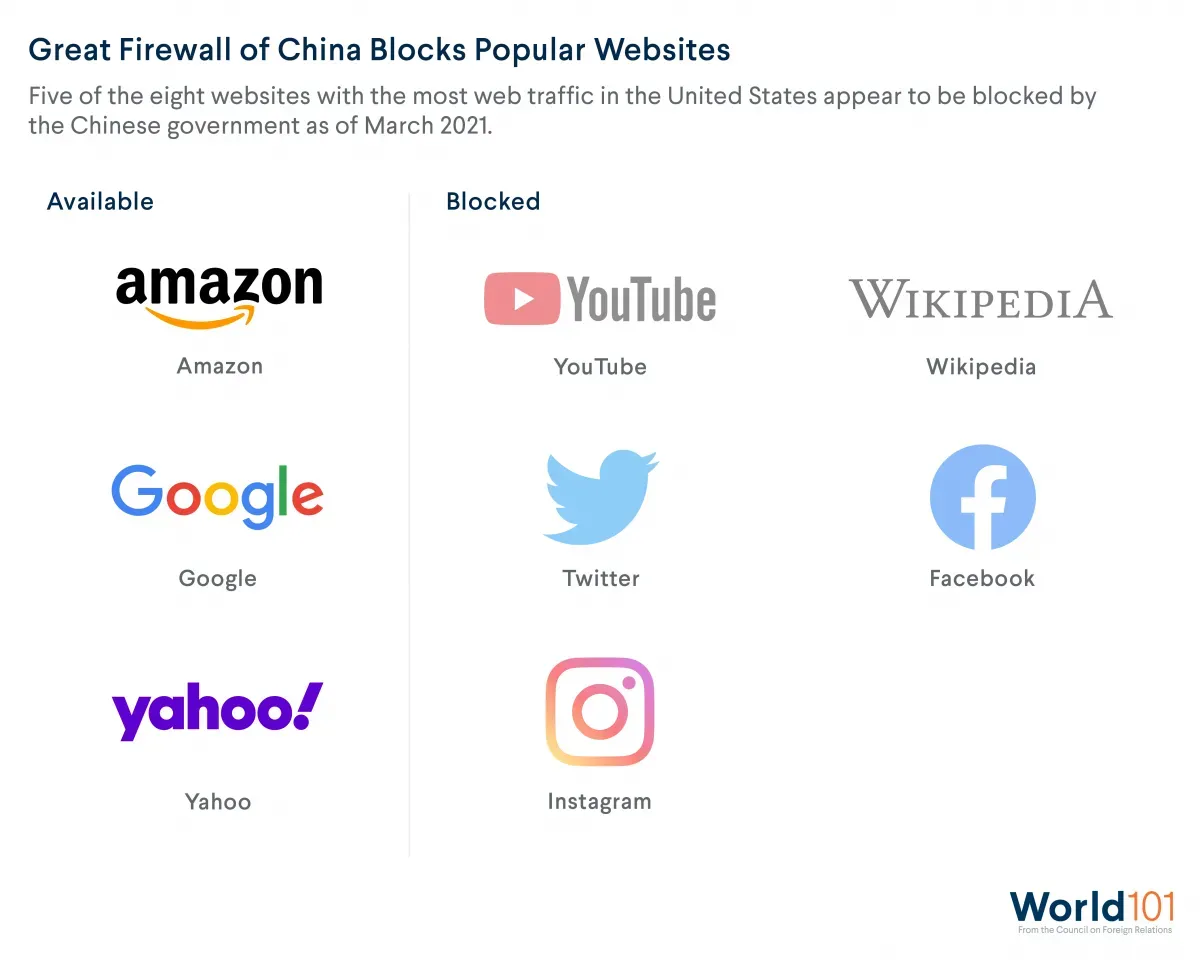

Today, the CCP still has a monopoly on political power in China. In fact, its grip on the country has only grown stronger under the current president, Xi Jinping—arguably China’s most influential leader since Mao. Under Xi, China has entered an era of “reform without opening up,” with the CCP backtracking on decades of liberalizing changes. In recent years, the party has cracked down on civil society and ramped up its system of highly effective internet censorship that some have dubbed the Great Firewall. The CCP has also eliminated presidential term limits—paving the way for Xi to preside in perpetuity. Meanwhile, Xi has departed from Deng’s strategy of keeping a low profile on the global stage and instead initiated a more aggressive foreign policy.

Although Xi has broken with tradition in many ways, he follows in the footsteps of previous CCP leaders. Specifically, he uses China’s past—especially its century of humiliation— to remind the public of what can happen without strong CCP leadership. This tactic was on clear display when Xi gave a speech outlining his vision for the future of China on November 29, 2012. After touring a museum exhibit on Chinese history starting with the First Opium War, Xi announced his plans for the revival, or national rejuvenation, of China.

Xi has pursued the “Chinese dream” of national rejuvenation at home and abroad through policies seeking to restore what was lost during the century of humiliation. These areas of focus include international standing, territory, and domestic control. Here are just a few outcomes of those policies:

International Standing: China has become the world’s second-largest economy. The nation’s GDP per capita has surged more than one hundredfold since 1960. But in recent years, this breakneck economic growth has slowed, leading the CCP to seek new markets abroad to sell its goods and services. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is President Xi’s signature foreign policy undertaking. Under BRI, Chinese institutions have loaned hundreds of billions of dollars to dozens of countries for infrastructure improvements. Investment in projects such as new railways, roads, and bridges have helped make China the world’s largest creditor over the United States and organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Although BRI projects have the potential to raise global income by 3 percent, they have increased indebtedness in host countries to a worrying level. Some countries have begun to question the economic feasibility of projects. Meanwhile, others criticize BRI projects’ disregard for human rights and their funding of nonrenewable energy sources like coal-fired power plants. Despite these issues, the massive scale of China’s economic policies reveals how far China has come in just decades. The country could even have the world’s largest economy by 2028. However, China’s GDP per capita would remain far lower than the United States’.

Shanghai Then and Now

Use the slider to see the changes.

This rapid growth has also increased both the interdependence and rivalry between the world’s two largest economies: the United States and China. Responding to what it viewed as unfair Chinese trade practices that were inconsistent with its World Trade Organization commitments and cost American jobs, the administration of former U.S. President Donald Trump imposed heavy tariffs on Chinese goods. These free trade restrictions pressed China to implement reforms and close the growing bilateral trade deficit. The move resulted in increased trade friction that saw multiple rounds of retaliatory tariffs imposed by both sides. In addition, the United States and China are battling over the technologies of the future. For example, the United States ordered a halt of exports to China’s Huawei telecommunications firm. Conversely, the CCP has pushed to develop artificial intelligence technology to help the Party control China’s vast population.

Territory: Throughout Chinese history, various dynasties ruled over different spans of territory. Today, the CCP uses select moments from that history to justify its territorial claims over disputed areas. Take Taiwan, for example. The Dutch colonized Taiwan’s indigenous population in the seventeenth century. After the Qing dynasty took control of China, it loosely governed the island until Japan wrested it away in 1895. After losing the civil war to the Communists, the Nationalists fled to Taiwan and relocated their government there in 1949. The Nationalists imposed martial law on the island’s residents until it began the process of democratization in the 1980s.

The CCP, meanwhile, claims Taiwan as an inalienable part of China and views it as a renegade province. However, the CCP makes this claim without actually having ever ruled over the island. The CCP has stated it is willing to use force, if necessary, to prevent Taiwan’s emergence as an independent country. Xi Jinping has made “unification” with Taiwan a central precondition to achieving the “Chinese Dream.”

In response, Taiwan has sought strong ties with the United States to ensure its security. However, the United States has walked a diplomatic tightrope in its policies toward the island. Three U.S. communiques (1972–1982) recognized the CCP’s stance “that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of China” and also downgraded U.S.-Taiwanese relations to become unofficial. Meanwhile, the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act promised the U.S. government would “consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means of grave concern to the United States.” Today, the United States sells advanced weapons to the island. But it also maintains a policy of ambiguity on whether it would defend Taiwan with force should China attack it.

The CCP has also used history to support its claims to territory in the South China Sea—specifically, a mid-twentieth-century map that it inherited from the Republic of China showcasing a dashed line that the government argues demarcates its sovereign maritime territory. An international court ruled that these claims had no basis in international law. However, that decision has not stopped the CCP from building man-made islands and military installations in the disputed waters. In 2018, President Xi declared that China would not cede “even one inch of the territory left behind by our ancestors.” Meanwhile, the United States, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam continue to contest China’s claims.

For more on China's territorial claims and border disputes, check out The China-India Border Dispute: What to Know and Tensions in the East China Sea.

Domestic Control: Xi’s “Chinese dream” seeks to establish a “harmonious” society. The CCP has used this vision to justify the brutal repression of ethnic minorities and political dissent. In the Xinjiang region, the government has set up a sweeping surveillance system and destroyed thousands of mosques. The CCP has also detained over one million Muslims (mostly of the Uyghur ethnic group) in shadowy facilities, where they have been made to endure “reeducation,” forced labor, and forced sterilizations. In 2021, the United States declared this behavior amounted to genocide.

Meanwhile, the CCP has sought to bring Hong Kong—a former British colony and special administrative region of the PRC since 1997—more firmly under its control.

The push to exert authority over Hong Kong has been widely viewed as a violation of the “one country, two systems” framework that was established ahead of the 1997 handover. Under the agreement, Hong Kong was guaranteed a significant degree of economic and political autonomy. The “one country, two systems” framework was designed to protect civil liberties such as freedom of the press and the right to assemble in Hong Kong. In exchange, matters of diplomacy and defense were left to Beijing. The framework was set to expire in 2047.

In 2020, however, the CCP passed a new national security law criminalizing most forms of protest in Hong Kong. This oppressive measure effectively wiped out political opposition and led to the arrests of dozens of high-profile activists. The law, which was supported by pro-Beijing lawmakers in Hong Kong, came on the heels of months of major protests against CCP encroachments. As a result of this crackdown, thousands of people have left or are trying to leave the island.

These developments in Hong Kong have also pushed Taiwan further away from the mainland, as the concept of “one country, two systems” has lost its credibility and appeal to the vast majority of Taiwanese people.

China on the World Stage

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the CCP has used its version of history to argue that a strong government is essential to protect China from foreign incursion. The CCP has leveraged history to restore the country to a long-lost position of global power. This narrative has been used to advance the government’s domestic and foreign policy goals, sparking both internal conflict and friction with other countries like the United States.

With differing understandings of history and competing visions for the future, the United States and China have come into competition in several ways. In recent years, the two countries have been locked in a trade war, imposed economic sanctions on one another, and leveled accusations of meddling in the other’s domestic affairs. None of these issues has come close to triggering an actual war. However, the contentious relationship between the world’s two largest economies has serious implications for regional and world order.

Despite disagreements on how the past informs the present, the United States and China—among others—will need to find a way to manage their increasingly sharp competition. The two countries are also responsible for working together to tackle shared challenges. No nation can deal successfully with global challenges—such as climate change or the COVID-19 pandemic—entirely on its own.