How Did Mass Production and Mass Consumption Take Off After World War II?

Discover how consumer goods have become cheap and ubiquitous in the global era.

Teaching Resources—Global Era: Economy (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

In 1954, microwaves sold for today’s equivalent of $30,000. Now, they can easily be purchased for under $50.

This steep discount isn’t just some big-box store’s latest supersale. Rather, it’s part of a broader trend of plummeting consumer goods prices in recent decades.

In large part, this trend dates back to the aftermath of World War II, a time during which producing goods became faster and cheaper. Decreasing labor and technology costs, soaring efficiency in manufacturing, and burgeoning global supply chains contributed to falling prices for average consumers. What’s more, rising incomes and innovations like consumer credit meant that people could buy goods that were once too expensive.

This emergence of cheap consumer goods allowed the largest global population in history to enjoy the highest average standard of living. However, such mass consumption also introduced its fair share of environmental and labor-related challenges.

This resource explores how goods became cheaper and how buying power increased, as well as the benefits and drawbacks of this new age of consumerism.

How have goods become cheaper?

Cheaper inputs: Throughout much of history, people used natural resources to create finished goods. To build a house, you’d chop down a tree for wood; to make medicine, you’d forage for plants; and to produce tires, raincoats, ships, and tanks, you’d harvest vast amounts of rubber.

If a community lacked those resources, it would need to import them—sometimes from faraway places. This process of trade could be costly and time-consuming. In the late 1930s, for example, the United States imported nearly 97 percent of its rubber from plantations in Southeast Asia.

But around this time, manufacturers began creating synthetic—or, factory produced—alternatives to many natural resources, which drove down prices and manufacturing time. During World War II, the U.S. military used synthetic rubber substitutes like plastic to create everything from pocket combs to aircraft windows. After the war, plastic also replaced steel in cars, paper in packaging, and glass in bottles.

The development of these new materials made previously cost-prohibitive appliances affordable for middle-class consumers. Radios fell from around $90 to just $10 in the 1930s as plastic replaced wood and steel components. Plastic use is so pervasive that it is nearly impossible to go a day without using something at least partially made from the material. Essential products like a coffee maker, a subway car, or a television are all made from this synthetic material.

Automation: Before factories existed, highly skilled workers individually handcrafted items such as books, clothing, and furniture. The pace of production was slow, and in turn, goods were often expensive and scarce.

But in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a period of groundbreaking innovation called the Industrial Revolution upended manufacturing. New technology allowed entrepreneurs to automate parts of production. Meanwhile, factories—which had become increasingly common—made manufacturing faster and cheaper by utilizing a system of division of labor in which each worker repeatedly performed the same small task.

These forces only accelerated in the twentieth century. Take car manufacturing, for example. In 1913, Henry Ford revolutionized the industry by implementing the moving assembly line. This innovationreduced the time it took to produce a single car from twelve hours to just over ninety minutes. As a result, the cost of Ford’s cars fell from today’s equivalent of $23,585 to just $4,000.

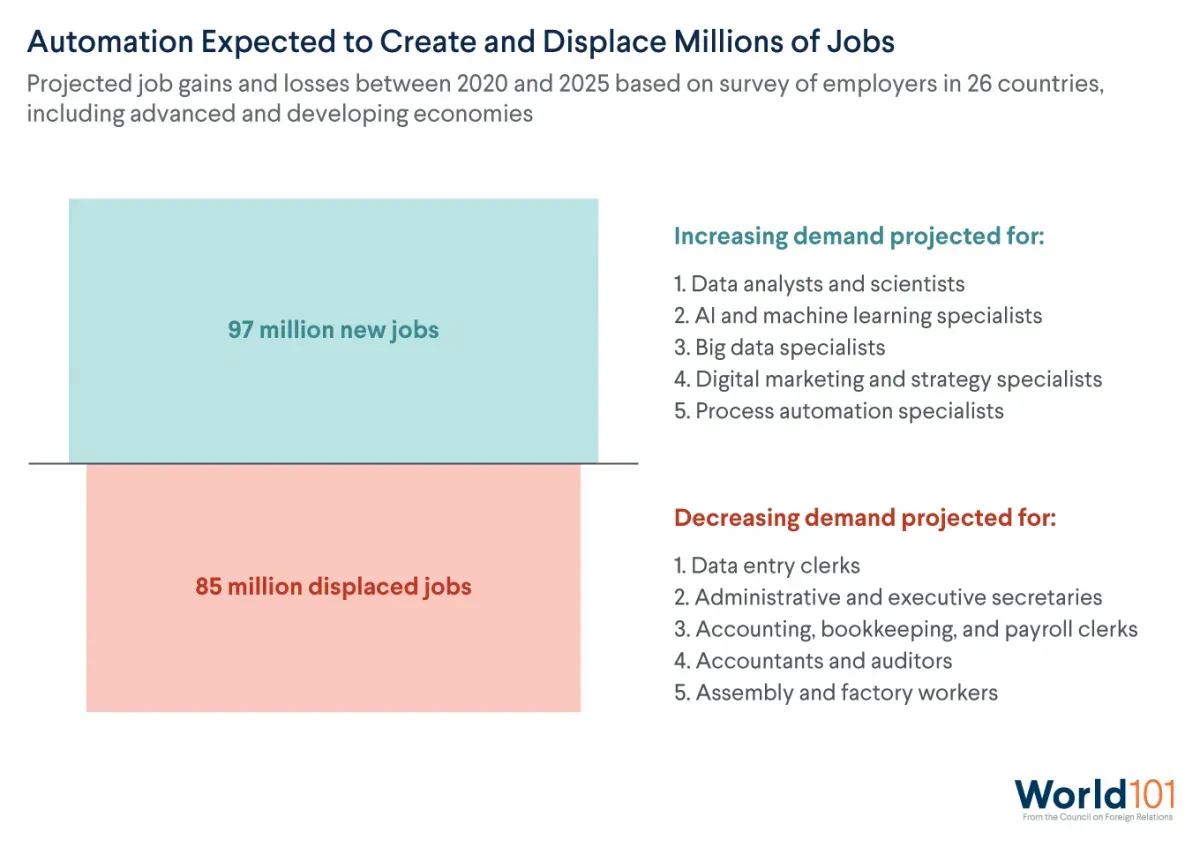

Since then, robots and other advanced technologies have continued to expedite tasks across numerous industries. Automation has increased production speeds and driven down production costs. In many instances, these innovations have completely replaced work once done by humans; however, some experts believe that increased automation will produce more new jobs than it eliminates.

Here are some examples of how automation is changing certain industries:

- Auto Industry: Nearly thirty percent of all industrial robots at work today are found in the automaking industry. With over 100,000 robots installed annually, carmakers typically deploy their automated workforce for repetitive welding and painting jobs. And while some automakers like Tesla have attempted to fully automate their factories, this approach hasn’t met with much success because many carmaking tasks still require a human touch.

- Health Care: Service robots, programmed to complete tasks like cleaning, stocking, or delivering medicine, and surgical robots, which are often operated by humans and used to enhance precision during surgery, are widely at use across the health-care industry. Beyond serving as a support for doctors, nurses, and staff in medical facilities, rapid advances in health-care robotics may soon usher in an era where robots travel to patients as opposed to patients traveling to the hospital for surgery.

- Agriculture: The possibilities for robots to disrupt the labor-intensive field of agriculture are many, from pickers and weeders, to crop monitors. The industry has its eyes on robots as a way to complete tasks undesirable to humans and as a way to increase efficiency on farms. For example, using robots reduces the time it takes to harvest strawberries by up to 40 percent.

- Transportation Industry: Though the technology that powers automated vehicles, or AVs, has advanced rapidly in recent decades, a future dominated by AVs won’t be reached without navigating some speed bumps, in particular the need to update related legal and financial systems. But the number of companies already operating in the space—fifty-two companies have permits to test AVs on California’s roads alone—has led many scholars to highlight those who drive for a living, from long-haul truckers to ride-share and delivery drivers, as parts of the workforce most vulnerable to automation.

- Restaurant Industry: Already, automation allows customers to order and pay for food using a kiosk or table-side tablet, eliminating a server’s role. But automation is being introduced to the food preparation process too, via machines used to complete repetitive tasks such as making coffee or assembling burgers. One upside? Often, these machines are faster, more consistent, and more sanitary than human workers.

Free trade: Following World War I, Congress enacted economic policies aimed at shielding domestic industries from foreign competition. On the surface, policies that purport to put the nation’s economic interests first seem fine, but in reality, they can hurt the country’s citizens. Tariffs (or taxes) increase the prices of imported goods, leaving consumers to bear the brunt of added costs. And when one country imposes tariffs on goods from another, it usually faces retaliatory tariffs on its own exports.

This scenario is exactly what unfolded in the early 1930s after Congress raised tariffs on hundreds of items through the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. Other countries responded with their own tariffs, making American products less competitive in foreign markets. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act reduced the total amount of international trade and worsened the economic fallout during the Great Depression.

After World War II, countries tried to reverse course and promote international economic cooperation. Twenty-three countries signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). It established a new rules-based trading system that sought to lower trade barriers like tariffs and create rules for how countries should trade freely. Indeed, the GATT and its successor organization, the World Trade Organization, have helped bring average tariffs today to under 3 percent—down from more than 20 percent in 1947. This has increased consumers’ access to more affordable products and inspired innovation as companies compete on the international market.

In today’s global era, such international trade is essential. No country can produce everything it needs at reasonable prices within its borders. Instead, a country will be richer if it makes what it is best at and imports what it is not as efficient at producing. This idea is known as comparative advantage. The United States, for instance, sells airplanes to countries around the world but imports products like coffee and tea from elsewhere.

Global supply chains: Decreasing tariffs also enabled manufacturers to assemble goods more cheaply across multiple countries. A Converse sneaker, for instance, sources materials for its soles, canvas, and shoelaces from different countries before assembly in another, Vietnam, where labor costs are low. Such global supply chains allow consumers to pay a lower cost for the shoe than if it were produced all in one country.

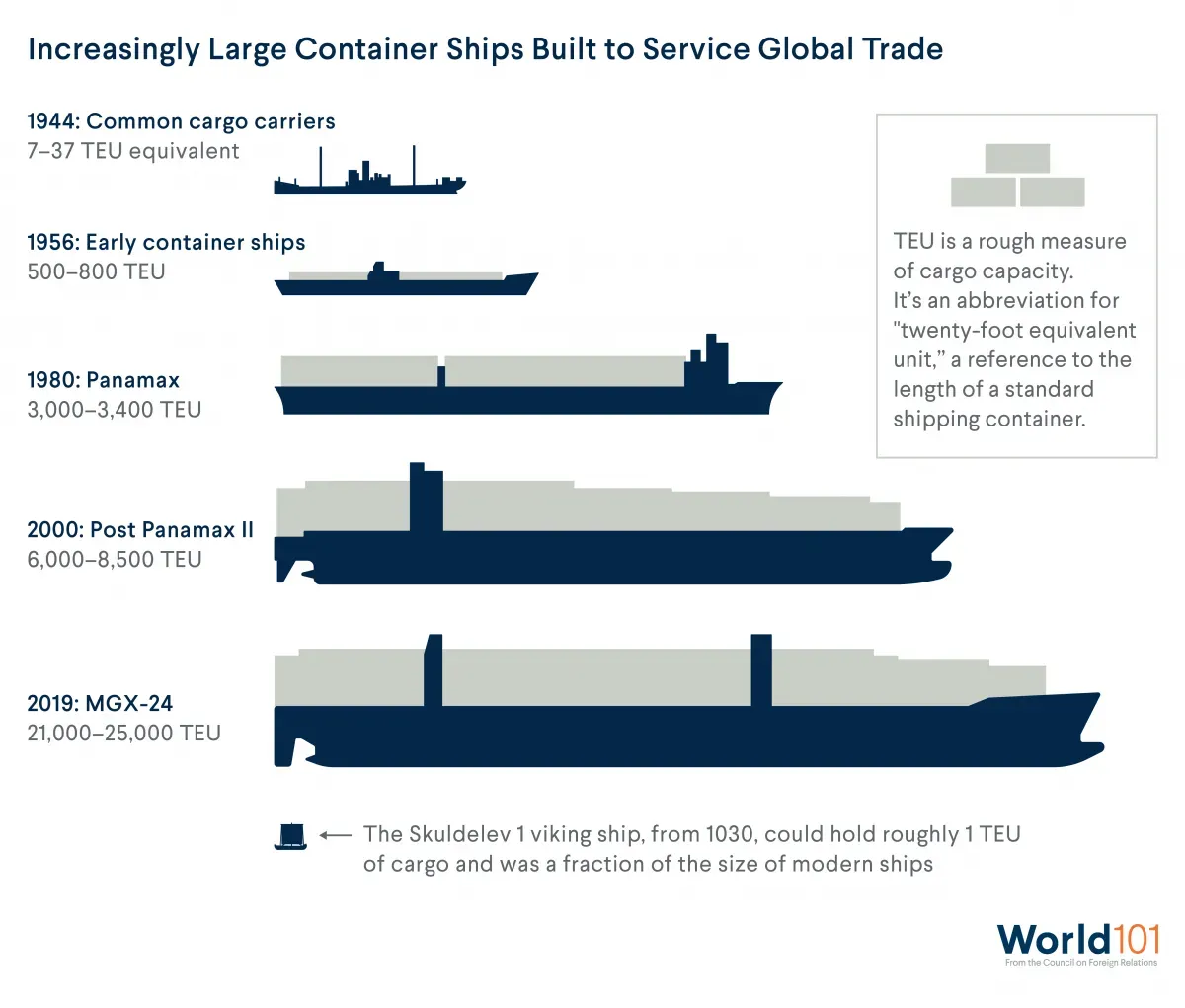

Free trade alone, however, did not enable the rise in global supply chains. Technological innovations like the container ship in 1956 allowed more cargo to be shipped across the world at cheaper prices. Additionally, policies like the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act allowed the industry to set its fares and routes, which further brought down the cost of transporting goods.

Although global supply chains benefit consumers and producers, reliance on foreign suppliers for essential goods presents challenges as well. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States and other countries struggled to acquire personal protective equipment when their primary supplier, China, halted exports. China similarly supplies the United States with a majority of its rare earth minerals—used in iPhones, missiles, satellites, and other critical products. As a result, when the two countries launched a trade war in 2018 fears emerged of export restrictions and economic pain. Beyond political rifts, natural disasters and armed conflict in one country can threaten the acquisition of goods in another.

How has buying power increased?

Higher incomes: In addition to goods becoming cheaper, consumer buying power increased in the period between the end of World War II and the 1970s. This era is known as the Golden Age of Capitalism.

Increases in productivity and consumption led to high levels of employment and rising incomes. During World War II, American manufacturers produced massive amounts of supplies for the U.S. military and its allies; shipbuilders in the Bay Area built a boat a day while Ford produced a bomber plane every hour. After the war, manufacturers catered to surging consumer demand for goods following years of strict wartime rationing. With this burst in industry, median U.S. incomes doubled between 1947 and 1965.

This postwar economic growth was not limited to the United States; between 1945 and 2000, nearly all people living in developed economies experienced rising incomes, making it possible for families to buy previously cost-prohibitive goods. However, in some places, this trend of rising incomes has since largely stalled out. In the United States, productivity has steadily risen since World War II, but pay has not increased at the same rate since the 1970s, contributing to a rise in economic inequality.

For more on economic inequality, check out The U.S. Inequality Debate.

Birth of consumer credit: Rising incomes, population growth, and new advertising strategies increased the postwar demand for goods. But the emergence of consumer credit was arguably the most powerful force. The credit card increased consumption by making it easier for people to spend more money than they had in their bank accounts.

The first universal credit card—the Diners Club Card—started in 1950 with two hundred cardholders and fourteen participating restaurants in New York City. One year later, it counted over forty thousand members. By 2018, the United States saw nearly forty-five billion annual credit card transactions. The total value of credit card transactions approaches $4 trillion.

Credit cards have been integral in the rise of e-commerce, allowing consumers to make online purchases from the comfort of their homes. However, credit cards are not without their drawbacks; almost half of all American adults hold credit card debt, which can be notoriously difficult to pay off given their high interest rates.

Companies cater to global markets: Increased access to consumer goods is not limited to the United States. Rather, international trade and rising incomes have meant that companies now sell their products to consumers around the world like never before. McDonald’s has restaurants in 118 countries, and Coca-Cola is available everywhere except Cuba and North Korea. The Coca-Cola Company even claims its brand is the second-most widely understood word in the world behind only “okay.”

Companies, however, can run into challenges operating in different countries with their own regulations. For example, Hollywood must follow strict rules to operate in China, the world’s largest film market. Hollywood studios must ensure their movies do not depict homosexuality, feature ghosts and the supernatural, or harm the interests and reputations of the Chinese state.

What are the drawbacks of mass production and mass consumption?

Environmental harm: The production of so much stuff depletes and pollutes ecosystems. For example, in Chile’s Salar de Atacama region, mining lithium—a mineral used in phones, laptops, and electric vehicles—contaminates soil and consumes 65 percent of the water supply, which has forced local communities to relocate. Similarly, fast fashion—low-cost clothing that is quickly thrown away—has helped make the apparel industry the world’s second-largest consumer of water. Today the fast fashion industry contributes 20 percent of all industrial water pollution worldwide.

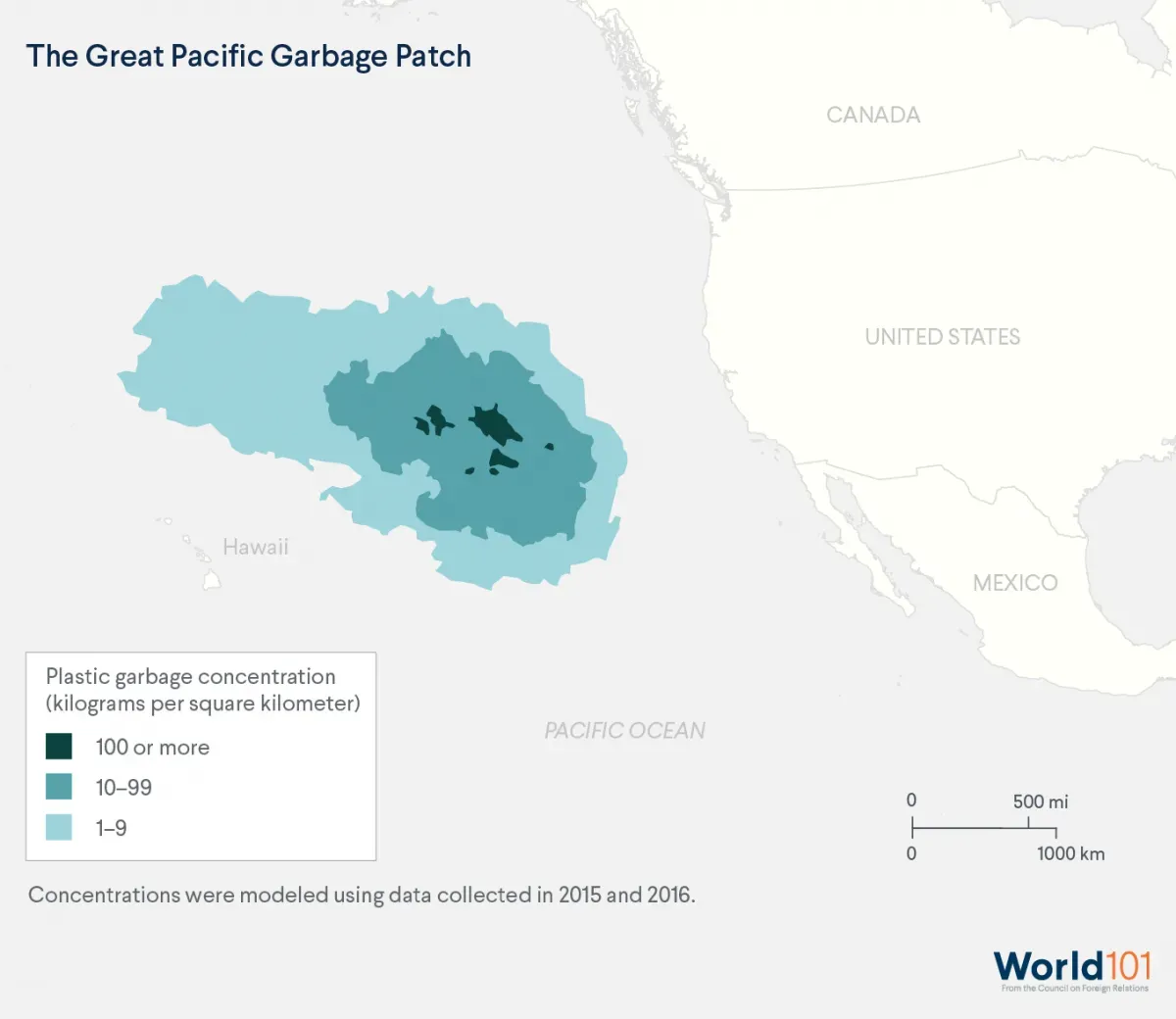

In addition, skyrocketing plastics production has led to hundreds of thousands of tons of the material ending up in oceans and rivers. This plastic, which can take centuries to decompose, becomes concentrated in certain areas, harming aquatic life. One such heap known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch covers an area twice the size of Texas.

Mass consumerism is also linked to climate change. A 2015 study found that household consumption accounts for around 60 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions. Greenhouse gases contribute to the severe effects of planet-wide warming, including longer-lasting heat waves, shrinking crop yields, and rising sea levels.

Innovation-associated job losses: For centuries, machines have replaced jobs once done by humans. Weaving machines replaced textile workers, modern telephones replaced switchboard operators, and computers replaced typists. In manufacturing alone, 1.7 million jobs have been lost to robots since 2000.

Moving forward, artificial intelligence and new forms of automation will continue to reshape both low-skilled jobs like trucking and manufacturing and high-skilled professions like law and medicine. Whom these changes will benefit and how they will reshape society is difficult to know. Automation will undoubtedly eliminate many current professions; however, it will also add new jobs to fields such as data management, computer science, and artificial intelligence—and create new roles not yet even conceivable.

How politicians and companies respond to such innovation will have lasting implications for the workforce of the future. The stakes for policymakers are particularly high as many ordinary people believe those in power are not addressing their concerns.

Exploitative labor practices: Many jobs are performed in countries where workers receive exceedingly low wages. In Ethiopia, for example, garment workers received the equivalent of $26 a month in 2019, making them—on average—the world’s lowest-paid apparel industry workers. As a result, employees struggle to afford decent housing, food, and transportation.

In many countries with such cheap labor, human trafficking and other exploitative labor practices can go unchecked. For instance, experts estimate that the Chinese government forces more than eighty thousand Uyghurs to work in factories across the country. Those factories service the global supply chains of major international companies such as Apple, BMW, Nike, and Samsung.

Mass consumerism in a global era

Indeed, innovations over the past several decades—including advanced robotics, modern shipping containers, and global supply chains—have raised living standards around the world. Mass consumerism has generated economic growth, and driven higher incomes. These developments have shaped today’s interconnected world in which people, ideas, money, and goods can crisscross the globe at unprecedented speeds.

But it’s important to remember that every benefit comes with costs. That pair of cheap jeans, for example, may only have its super low price tag if it’s made with low-wage labor in a process that’s harmful to the environment and contributes to climate change.

As manufacturing in the future likely becomes even faster and cheaper than it is today, the price of many goods may continue to drop. But as these changes occur, it will remain important to consider what factors made them possible, who benefits, and who may be left behind.