It Takes a Village to Make Your Medicine

Follow the global supply chain across borders and into your pill bottle.

Teaching Resources—Globalization: Introduction (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

The pills in your medicine cabinet take just minutes to travel through your bloodstream. Have you considered the journey each of those pills took to get to you?

How and why are U.S. pharmaceuticals produced abroad?

As recently as a few decades ago, medicines consumed in the United States were primarily manufactured at home (or in Europe) and were made using ingredients that originated there. This setup began to change in the 1980s, when trade liberalization relaxed restrictions and introduced regulations to promote free trade among countries. This allowed companies to expand abroad, where ingredients were cheaper and companies were subject to fewer restrictions and regulations.

In the 1990s, the first finished medications made in India began arriving in the United States, and the trend has only accelerated since: today, the United States is the largest importer of pharmaceuticals worldwide. Nearly half of the drugs Americans consume come from abroad, as do virtually all of their necessary ingredients.

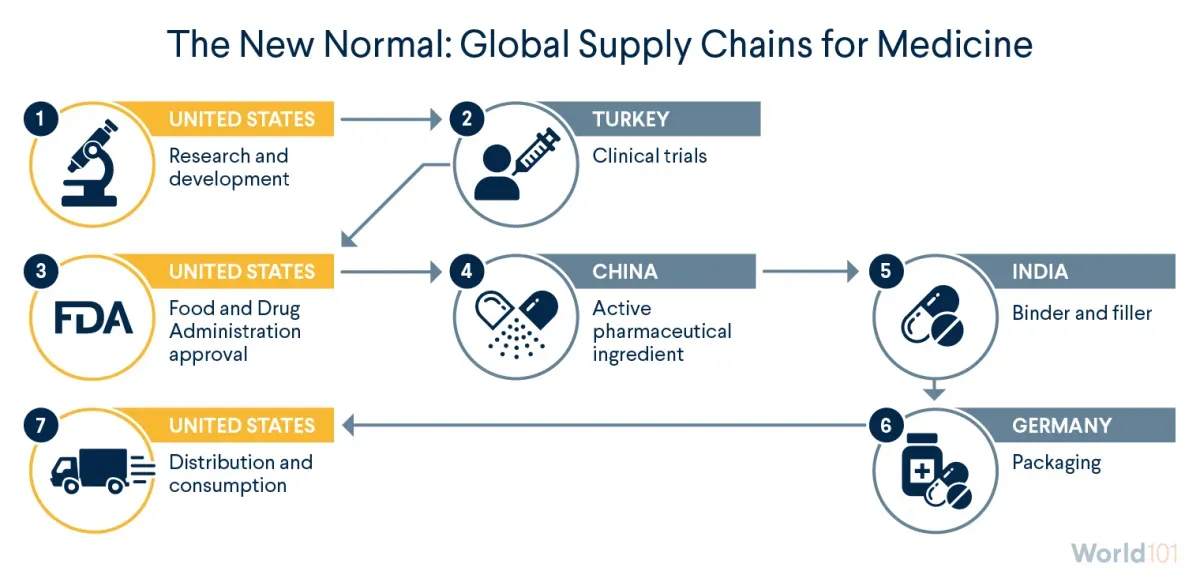

How does the global supply chain work for U.S. pharmaceuticals? Depending on the product, the company, and other factors, your medicine can travel through different paths. Here is one possible path, informed by data from medical and government organizations.

United States: Research and Development

Typically, the journey begins in the United States, where scientists and drug companies, sometimes with government financing, work to identify new and improved medications. They conduct experiments to see, for example, how different compounds react and what dosages might work best. Once they have identified something promising, they conduct preclinical research—think test tubes and petri dishes—on microorganisms and animals to determine if the drug is safe to test on humans.

Turkey: Clinical Trials

If all goes well, the next step is a clinical trial—human testing. Clinical testing involves several phases, of increasing complexity and length, and few drugs make it to the finish line.

Today, more companies are opting to conduct testing outside of the United States, mainly for the same reason they source more materials abroad: fewer regulations and lower costs. Depending on the country, overseas clinical trials can cost up to 60 percent less than they would in the United States. But many of these trials have also raised ethical concerns, in particular regarding the potential exploitation of participants from low-income environments asked to take on the risk of experimenting with new treatments they probably won’t be able to afford in the future.

As recently as 1990 … a mere 271 trials were being conducted in foreign countries of drugs intended for American use. By 2008, the number had risen to 6,485.

In recent years, Turkey has become home to more research activity for a number of reasons, including its unique geographic location straddling Asia and Europe, its emerging economy, its large population with low levels of pharmaceutical use, and the relatively low costs of testing, which still meets European standards. Nearly two thousand clinical trials took place in Turkey between 2012 and 2018, up from twenty-three conducted between 1994 and 2000.

United States: FDA Approval

Data collected at clinical trials then heads to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval. The approval process and duration vary by drug type; a standard process takes about one year. Once the drug is approved, production begins.

Most new drugs proceed into the market under patents that bar other companies from copying their inventions. But when those patents expire (many are set at twenty years), others can replicate those drugs and produce their own equivalent—or generic —medications for much cheaper.

China and India: Ingredient Sourcing

The substance that directly attacks the problem a medication aims to solve is called the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). China produces most of the world’s APIs, making it likely that one of the medicines you take has Chinese ingredients.

The next stop could be India, which runs more than 10 percent of the world’s facilities for making finished medications. India is a frequent provider of binders and fillers—ingredients that hold a pill together and give it shape. One example is lactose, which binds ingredients tightly and bulks up a pill to make it easier to swallow.

Germany: Packing

After the medication is assembled, it is packaged. Germany has been a large source of the United States’ packaged medications imports and in 2019 was the largest exporter of pharmaceutical products to the world.

United States: Distribution to U.S. Consumers

The supply chain ends where it started: in the United States. After wholesale distributors purchase drugs from manufacturers and send them to pharmacies, hospitals, clinics, and elsewhere, the final stop for a medication is your medicine cabinet.

The Consumer: What the Global Supply Chain Means for You

Medicines are not the only things that pass through the global supply chain—it’s part of nearly every product in our daily lives, including what we eat and wear. Understanding how products move through the world before they land on our shelves can help us make informed decisions about what we choose to buy, sell, and use.