The History of Terrorism and U.S. Counterterrorism Since 1945

From the creation of the CIA to the “War on Terror,” learn about the evolution of U.S. counterterrorism policies in this terrorism timeline.

A U.S. Army soldier stands guard from atop a tower at maximum security prison Camp Delta at the Guantanamo Naval Base on August 25, 2004 in Cuba.

Source: Mark Wilson/Pool via Reuters

Teaching Resources—Terrorism: Confronting Terror (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

It is easy to imagine that U.S. counterterrorism policy began as a response to the 9/11 attacks. But efforts to stop terrorism have spanned modern American history—though who was designated a terrorist, and how seriously the threats were taken, shifted dramatically over time.

What is counterterrorism?

Counterterrorism is the set of policies and actions—including intelligence collection and analysis, military action, and homeland security measures—designed to combat terrorism.

During the Cold War, the terms "terrorist" and "subversive" were largely reserved for Soviet-backed insurgents abroad, and communist sympathizers at home. The label was even attached to civil rights leaders campaigning for equality. American presidents viewed terrorism as a tactical threat, a low-impact security challenge that warranted only limited attention. The Soviet Union and its allies posed the greater strategic challenge. The collapse of this arch rival in 1991 initiated the first shift in the United States' national security priorities. A decade later, the catastrophic events of 9/11 fundamentally restructured the United States’ national security priorities. Once considered a criminal act, terrorism is now seen by U.S. policymakers as an existential threat, both at home and abroad.

In this timeline, we examine the vastly different ways in which U.S. administrations have defined and prioritized domestic and foreign terrorist threats. We look at how these policymakers have balanced the national security agenda with civil liberties such as the right to privacy and the right to a fair trial. This timeline is not an exhaustive list of counterterrorism policies and operations; it rather serves to illustrate changing priorities that led to today’s two-decade-long war on terror.

Timeline: U.S. Counterterrorism Since 1945

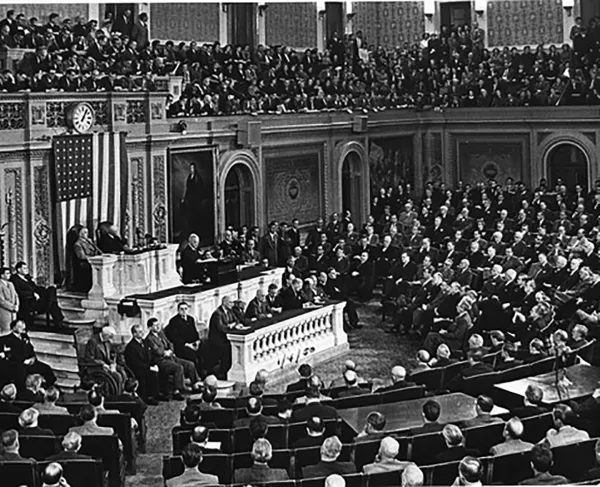

The Soviet Union emerged as an international superpower in the wake of World War II. In response, President Harry S. Truman passed a series of sweeping domestic and international policies. These actions aimed to confront and contain this rising global competitor. One such measure entirely restructured the United States’ military and intelligence agencies, forming the basis of today’s U.S. national security apparatus.

Abbie Rowe/National Park Service via Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

Abbie Rowe/National Park Service via Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

Abbie Rowe/National Park Service via Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

The National Security Act of 1947 established the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency, the first peacetime intelligence agency. This structure remained in place until 2004 when Congress created a new office—the Director of National Intelligence. This role was created to effectively coordinate and promote information-sharing across the U.S. intelligence community. The National Security Act, along with a 1949 amendment, also created the Department of Defense. This executive department is led by a secretary who oversees the Army, Navy, and Air Force, the same basis of today’s U.S. military.

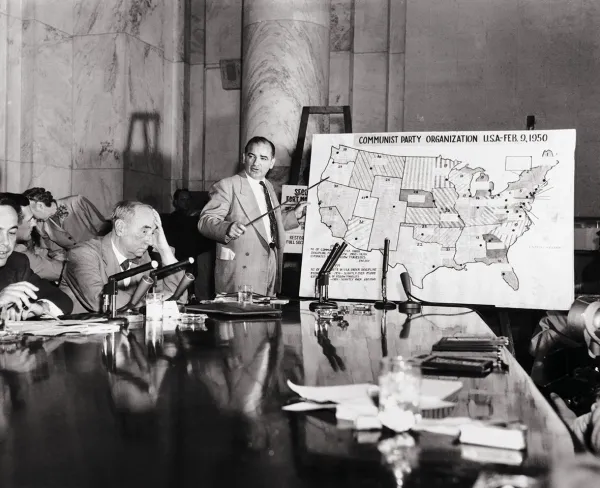

American fears of communists, radical leftists, and anarchists spread in the early twentieth century amid attacks against politicians, judges, and bankers. This period from 1917 to 1920 is known as the First Red Scare. President Dwight D. Eisenhower took office three decades later when American policymakers once again feared communism due to growing Soviet global influence. The FBI more than doubled in size throughout the forties and fifties in a wave of anti-communist hysteria led by Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy. This period—known as the Second Red Scare or the era of McCarthyism—was marked by political repression. During the era of McCarthyism, the careers of thousands of politicians, academics, and entertainers were destroyed by accusations of communist sympathizing.

Bettmann Archive via Getty Images

Bettmann Archive via Getty Images

Dan Grossi/AP

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover directed an aggressive FBI operation targeting domestic political organizations that he considered to be threatening to the “internal security” of the United States. Agents working on Hoover’s operation, called the Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), initially sought to disrupt communist groups in the United States. COINTELPRO served as a forerunner of modern-day domestic surveillance tactics such as those laid out in the post-9/11 Patriot Act.

The Cold War intensified during the John F. Kennedy administration, as the two global superpowers narrowly avoided nuclear war. Kennedy’s top priority was confronting Soviet influence at home and abroad, not combating terrorism. U.S. policymakers did not view international terrorism as an existential threat. Instead, the term terrorist was often used to refer to Soviet-backed insurgents and guerillas acting as Cold War proxies in locations such as Cuba and Vietnam.

Cecil Stoughton/White House via John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Cecil Stoughton/White House via John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Cecil Stoughton/White House via John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

In March 1963, the CIA reported that the United States was highly vulnerable to weapons of mass destruction—nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons—being smuggled into the country. Kennedy, however, did not implement any additional counterterrorism measures, in sharp contrast to today’s response to such threats. He believed that the Soviets—and only the Soviets—were capable of carrying out such an attack. According to Kennedy, it was highly unlikely that the Soviets would want to provoke nuclear war in fear of mutually assured destruction.

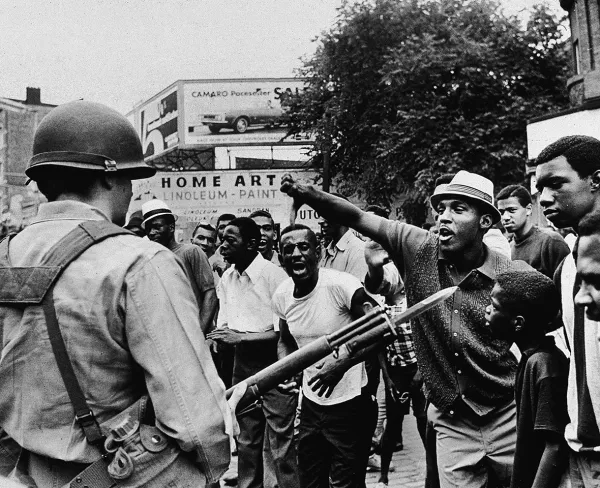

Following a decade of post–World War II prosperity that largely benefited white Americans, groups advocating for civil rights reform and other political change sparked domestic unrest. Reaction to this social upheaval dominated the counterterrorism agenda of the 1960s. Law enforcement resources were spent targeting domestic groups, individuals, and ideologies deemed threatening to national security.

Neal Boenzi/New York Times via Getty Images

Neal Boenzi/New York Times via Getty Images

Agence France Presse via Getty Images

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) tracked not just groups with alleged communist affiliations but also civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. COINTELPRO also sought to “neutralize” the activities of groups including the Black Panthers. However, under Hoover, COINTELPRO greatly exceeded the bounds of intelligence gathering. In 1964, the FBI went so far as to send an anonymous blackmail note to King, which appeared to insinuate that he killed himself. “You are done. King, there is only one thing left for you to do,” the letter read. “You know what it is.”

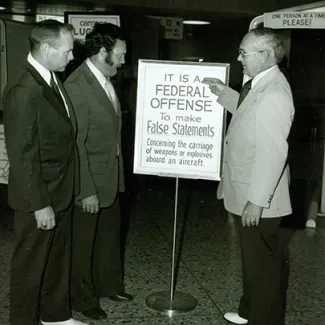

The U.S. government did not always view airplane hijackings as terrorist threats. Between 1968 and 1972, more than 130 airplane hijackings took place in the United States, occurring at a rate of about two per month. The vast majority were carried out by Americans trying to reach Cuba. These “skyjackings” became so common that the Swiss government, which represented American diplomatic interests in Cuba, created a form letter to request the return of the diverted plane, crew, and passengers. Finally, the Air Line Pilots Association, tired of having their planes overtaken by gun-wielding passengers, demanded tougher security. However, the airline industry and the federal government dismissed the idea as ridiculous. This lack of attention to airline security is a far cry from current policy in the United States.

Lynn Pelham/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Lynn Pelham/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

FAA News via Flickr

On November 11, 1972, three men armed with guns and hand grenades hijacked Southern Airways Flight 49. The hijackers threatened to crash the plane into a nuclear reactor in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, unless they were paid $10 million. Facing a potential nuclear disaster, Southern delivered part of this money to the hijackers, who refused to release the passengers and continued to Cuba, where they were arrested. Realizing the potential mass lethality of such hijackings, the Federal Aviation Administration began full passenger and carry-on luggage screening at American airports shortly thereafter, starting on January 5, 1973.

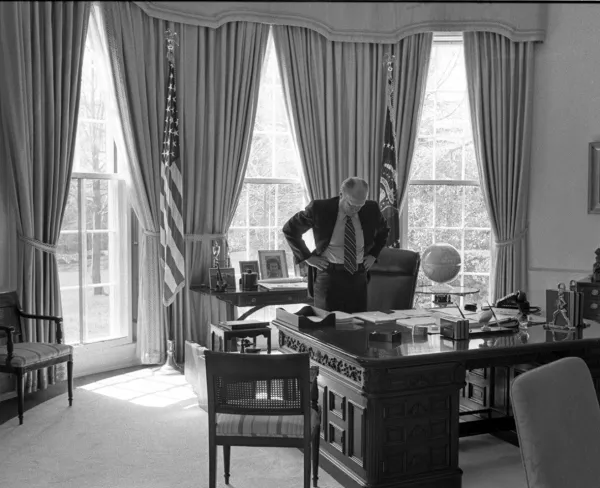

The American public profoundly distrusted the government following the Watergate scandal. The scandal resulted in Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974, prematurely ending his administration. Those feelings intensified four months into Ford’s presidency when the New York Times published a story, in December 1974, exposing yet another domestic surveillance operation, distinct from COINTELPRO. In this case, the CIA conducted a “massive, illegal domestic intelligence operation” called Operation Chaos, during the Nixon administration. Through Operation Chaos, a CIA unit kept files on ten thousand “dissident Americans” involved in anti-war activities and other protest movements. Truman’s 1947 National Security Act explicitly prohibited the CIA from conducting such internal security operations.

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

Boise State University Special Collections and Archives

The Senate convened a special committee to investigate abuses by the CIA, FBI, National Security Agency (NSA), and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The committee was tasked with unearthing information regarding unlawful domestic surveillance operations carried out by the intelligence community. The Church Committee—chaired by Idaho Senator Frank Church—issued its eye-opening final report in April 1976. The Church Committee exposed an even farther-reaching network of politically motivated intelligence operations taken against U.S. citizens. That same year, Attorney General Edward Levi created guidelines for government agencies, including rules that limited the FBI’s ability to gather domestic political intelligence. However, subsequent attorneys general significantly weakened these guidelines to today’s standard; it is once again easier for the FBI to surveil and investigate American citizens; such monitoring can occur even without clear proof of criminal activity.

American policymakers first seriously took notice of international terrorism as a threat to national interests in the 1970s. Amid a wave of high-profile attacks, perhaps most notably the killing of Israeli athletes in Munich at the 1972 Olympics, terrorism emerged on the radar of American national security and intelligence agencies. In response to these threats, the United States monitored not just individuals but also entire countries that supported terrorism. The Carter administration initially singled out four countries: Iraq, Libya, Syria, and South Yemen, which unified with the North in 1990. Each of these countries also had Soviet-leaning sympathies during the Cold War. The State Sponsors of Terrorism list today designates Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and Syria as state sponsors.

Eberhard Klöppel/Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

Eberhard Klöppel/Ullstein Bild via Getty Images

Jack Garofalo/Paris Match via Getty Images

Congress passed the State Sponsors of Terrorism list in 1979 primarily to control weapons sales during the Cold War. Previously, the United States could sell planes to Syria and military vehicles to Libya with little to no oversight. With the dual threats of the Cold War and rising international terrorism, the list acted as a tool to monitor and regulate the sale of U.S. military equipment to countries that were actively supporting terrorism. Over the past forty years, the list has grown into a powerful foreign policy instrument. The list is now utilized not only to monitor weapons sales but also to justify sanctions, travel bans, and similar actions.

Hundreds of U.S. citizens died at the hands of state-sponsored terrorist groups throughout the seventies and eighties. But unlike in the post-9/11 era, U.S. policymakers did not view such terrorist attacks as existential national security threats. Rather, these acts of terrorism continued to take a backseat to the Soviet threat; the Ronald Reagan administration believed international terrorism was an unavoidable reality during the Cold War. It would take a catastrophic attack on American soil to completely restructure the U.S. government and the way the country dealt with terrorism.

U.S. Army

U.S. Army

U.S. Marine Corps

Suicide bombers linked to Hezbollah, an Islamist militant group based in Lebanon, drove truckloads of dynamite into the barracks of U.S. Marines and French paratroopers, killing 305 people. Hezbollah’s attack was designed to expel foreign peacekeepers from Lebanon. Reagan promised a muscular response to what was then the deadliest terrorist attack in U.S. history. But the United States pulled out of a planned air assault with France, and the White House did little to support ambitious counterterrorism legislation when it stalled in Congress. Reagan’s response was typical for the Cold War period when, once again, conflict with the Soviet Union largely overshadowed the concept of international terrorism.

At the start of the George H. W. Bush presidency, the Cold War was nearing its end and new global threats were rising. American policymakers feared that deadly chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons from the Soviet Union could potentially fall into the arms of terrorists. Meanwhile, in the Middle East, Saddam Hussein’s regime had just ended a brutal war against Iran. During this conflict, Saddam flagrantly abused chemical weapons to massacre thousands of Iraqis in 1988.

Reuters

Reuters

Peter Turnley/Corbis via Getty Images

In 1975, twenty-two governments ratified the Biological Weapons Convention. This international treaty aimed to prevent nations from developing, stockpiling, and deploying biological and toxic weapons. Fourteen years later, the United States joined the convention by passing the Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act of 1989. The legislation sought to strengthen the United States’ defense against biological warfare and individuals who may use these weapons. It was even strengthened after 9/11 and is still in effect.

In the decade following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States enjoyed unprecedented global primacy. But the 1990s were also marked by terrorist threats against U.S. citizens both at home and abroad. In 1993, Ramzi Yousef carried out the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York. Two years later, Timothy McVeigh bombed a federal building in Oklahoma City, killing at least 168 people. The Oklahoma City bombing was the then-deadliest domestic terrorist attack. President Bill Clinton sought to enact powerful and unprecedented counterterrorism policies to address this growing threat.

Rick Wilking/Reuters

Rick Wilking/Reuters

Jim Bourg/Reuters

In the face of growing and varying terrorist threats, the Clinton administration proposed the first reforms to U.S. counterterrorism policies in nearly a decade. Known as the Omnibus Counterterrorism Act of 1995, the Clinton legislative initiative sought to grant the government significantly enhanced surveillance powers. Specifically, the legislation loosened restrictions on the government’s ability to listen in on phone calls. Many of the proposals closely resembled the Patriot Act, which would come into effect six years later. But unlike the George W. Bush administration, the Clinton administration faced steep bipartisan resistance in Congress who argued that the proposal would threaten civil liberties. The act failed to get through Congress. It would take another six years and the 9/11 attacks before Congress would seriously revisit such legislation. The failure of the Omnibus Counterterrorism of 1995 characterized the ongoing debate on the balance between civil liberties and national security.

In one of the deadliest terrorist incidents on record, militants from the terrorist group al-Qaeda hijacked four planes. They used them as weapons to kill 2,977 people and cause extraordinary destruction. The nineteen hijackers crashed two planes into the World Trade Center in New York and flew another into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. The fourth plane was heading toward Washington, DC when passengers overtook the terrorists and crashed the aircraft in Pennsylvania. After 9/11, U.S. counterterrorism strategy changed remarkably. No longer a marginal issue, counterterrorism took center stage in U.S. policy both at home and abroad. The attacks on 9/11 prompted two wars, a vast government reorganization, and a series of sweeping security measures.

Peter Morgan/Reuters

Peter Morgan/Reuters

Jim Hollander/Reuters

Three days after the 9/11 attacks, Congress authorized the president to respond militarily to those who had “planned” the 9/11 attacks and “harbored” the attackers. This law, the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), provided the legal basis for the invasion of Afghanistan and the start of the so-called war on terror. Thus began a war against a concept—terrorism—a conflict without end and certainly without clear boundaries. U.S.-led coalition forces retaliated against not only al-Qaeda, which had planned and carried out the 9/11 attacks, but also the Taliban, which had protected the terrorist group in Afghanistan. The war in Afghanistan spanned twenty years (2001-2021), becoming the longest in U.S. history. Over 2,400 Americans lost their lives in the conflict and more than twenty thousand were injured. The U.S. government spent over 2 trillion dollars in the “war against terror.”

Also in the aftermath of 9/11, and with the approval of the Bush administration, the CIA began apprehending and detaining individuals the agency suspected of being a threat to the country. These activities evolved into a covert program employing what the U.S. government labeled “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Meanwhile, critics described these techniques as torture. The tactics used included waterboarding, sleep deprivation, exposure to extreme temperatures, and confinement in small boxes.

In 2014, members of the U.S. Senate found evidence that at least thirty-nine people had been subjected to enhanced interrogation. The Senate’s report concluded that the program, which ended in 2008, “was not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees'' and “damaged the United States' standing in the world.”

The 2010s brought frequent reminders of the globalized threats of terrorism. Global deaths from terrorism soared starting around 2013. The increase in terrorist threats was largely due to the rise of groups such as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and Boko Haram in Nigeria. While the Bush administration launched the war on terror, the Obama administration expanded the scope of its operations to respond to these new threats. More than fifteen years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the Obama administration used the 2001 AUMF to carry out counterterrorism training or operations in six continents. Most notably, the AUMF authorized the killing of the al-Qaeda leader and 9/11 architect Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in 2011. In this expanding fight against terrorism, the Obama administration conducted drone strikes even in non-battlefield settings in Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen.

Mohammad Ismail/Reuters

Mohammad Ismail/Reuters

Staff Sergeant Suzanne M. Jenkins/U.S. Air Force

On September 30, 2011, the United States carried out a targeted drone strike in Yemen on a senior al-Qaeda recruiter and spokesperson, Anwar al-Awlaki, a U.S. citizen. The assassination of al-Awlaki marked the first time that the United States had deliberately killed an American citizen by drone strike. The drone assassination denied al-Awlaki constitutional rights to due process, including the right to a fair trial. The targeting of the radical cleric raised constitutional questions about the war on terror and shed light on the Obama administration’s increasing use of drone warfare. Obama authorized at least 542 drone strikes during his presidency, killing an estimated 3,797 people, including 324 civilians, though these numbers are difficult to verify.

Beyond the battle against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, the United States expanded counterterrorism operations across Africa in countries such as Libya, Niger, and Somalia. Notably, Trump focused on “radical Islamic terrorism,” threats he said “must be stopped by whatever means necessary.” Previous presidents avoided linking Islam—the second-largest religion in the world, with 1.8 billion adherents—to terrorism. But Trump consistently singled out Muslims in both his campaign rhetoric and actions as president, eliciting sharp criticism for anti-Muslim bigotry.

Carlos Barria/Reuters

Carlos Barria/Reuters

Dennis Bratland via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 4.0

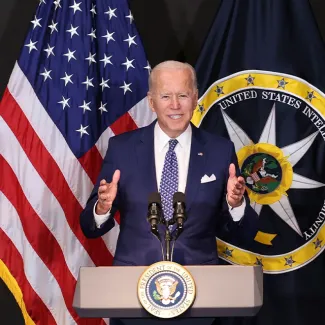

In 2017, just one week into his presidency, Trump signed Executive Order 13769. This executive order barred citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States and suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program. Despite the United States having some of the strictest immigration laws in the world, Trump argued that the order was vital for national security. The executive order—referred to by critics as the Muslim ban or the travel ban—faced significant protests, public condemnation, and legal challenges. It was ultimately replaced by a revised version, which the Supreme Court upheld. However, on his first day in office, President Joe Biden issued a proclamation ending the Trump administration’s travel ban.

Evelyn Hockstein / Reuters

For the first time in U.S. history, Joe Biden announced a strategy to combat domestic terrorism. This comes following a report released in October 2020 from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security stating that racially and ethnically motivated extremists will remain the most persistent domestic threat.

Reuters

The War in Afghanistan officially ended in 2021 as the United States withdrew its remaining troops from Afghanistan as outlined in a peace agreement signed in February 2020. Since then, the Taliban has taken power in the country. According to the UNDP, the Taliban has also wiped out gains in Afghans’ standards of living that were made over the two decades after the U.S. invasion.