The History of Terrorism and U.S. Counterterrorism Since 1945

From the creation of the CIA to the “War on Terror,” learn about the evolution of U.S. counterterrorism policies in this terrorism timeline.

It is easy to imagine that U.S. counterterrorism policy began as a response to the 9/11 attacks. But efforts to stop terrorism have spanned modern American history—though who was designated a terrorist, and how seriously the threats were taken, shifted dramatically over time.

What is counterterrorism?

Counterterrorism is the set of policies and actions—including intelligence collection and analysis, military action, and homeland security measures—designed to combat terrorism.

During the Cold War, the terms "terrorist" and "subversive" were largely reserved for Soviet-backed insurgents abroad, and communist sympathizers at home. The label was even attached to civil rights leaders campaigning for equality. American presidents viewed terrorism as a tactical threat, a low-impact security challenge that warranted only limited attention. The Soviet Union and its allies posed the greater strategic challenge. The collapse of this arch rival in 1991 initiated the first shift in the United States' national security priorities. A decade later, the catastrophic events of 9/11 fundamentally restructured the United States’ national security priorities. Once considered a criminal act, terrorism is now seen by U.S. policymakers as an existential threat, both at home and abroad.

In this timeline, we examine the vastly different ways in which U.S. administrations have defined and prioritized domestic and foreign terrorist threats. We look at how these policymakers have balanced the national security agenda with civil liberties such as the right to privacy and the right to a fair trial. This timeline is not an exhaustive list of counterterrorism policies and operations; it rather serves to illustrate changing priorities that led to today’s two-decade-long war on terror.

Timeline: U.S. Counterterrorism Since 1945

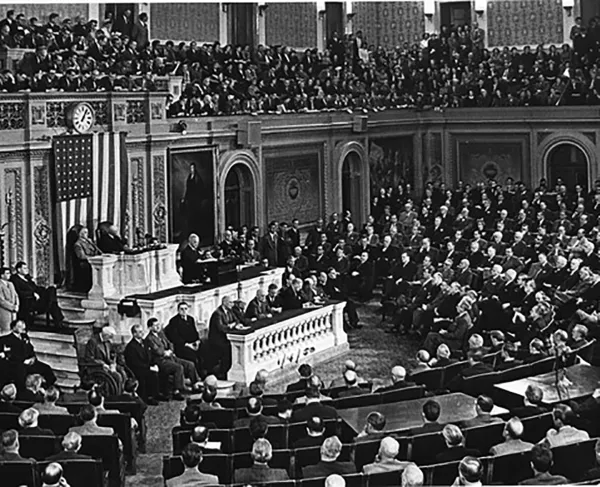

Harry S. Truman: New Security Priorities After World War II

National Security Act Creates the CIA

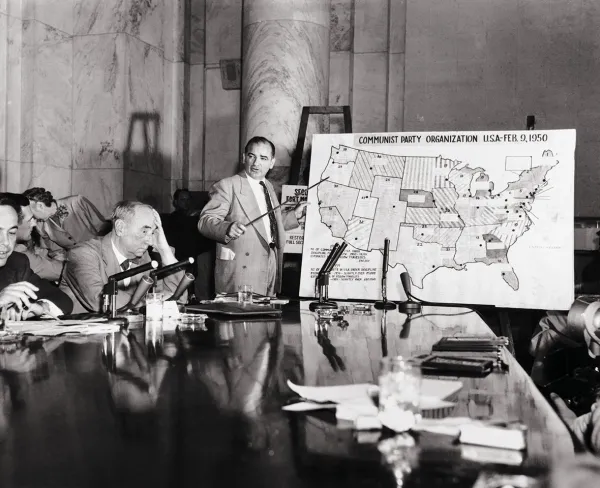

Dwight D. Eisenhower: Rise of the Red Scare

COINTELPRO Targets Communist Groups

John F. Kennedy: Showdown with the Soviets

CIA Warns of American Vulnerabilities

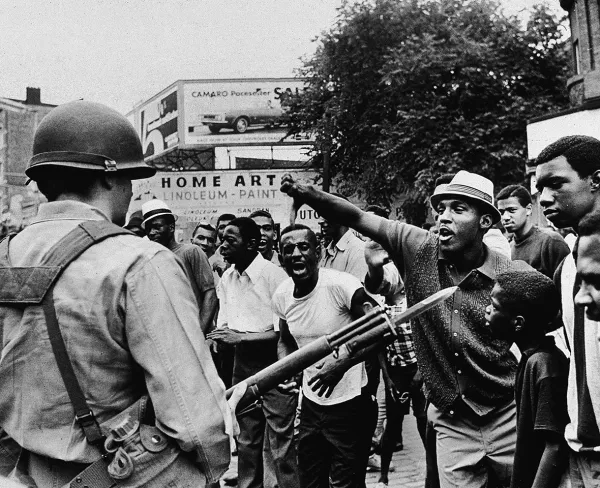

Lyndon B. Johnson: Social Unrest at Home

FBI Tracks MLK Jr., Civil Rights Leaders

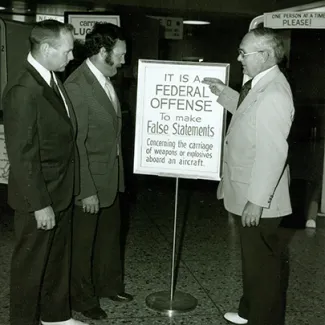

Richard Nixon: Hijackings in America

Southern Airways Flight 49 Scare Changes Airline Safety

Gerald Ford: The CIA and Domestic Surveillance

Senate Report Exposes Spying on U.S. Citizens

Jimmy Carter: State-Sponsored Terrorism

Congress Passes State Sponsors of Terrorism List

Ronald Reagan: International Terrorism and the Cold War

Beirut Barracks Bombing Kills Hundreds

George H. W. Bush: Rogue Threats and Weapons of Mass Destruction

U.S. Passes Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act

Bill Clinton: Terrorism in the National Spotlight

Congress Blocks Clinton Counterterrorism Bill

George W. Bush: 9/11 and the Aftermath

The Invasion of Afghanistan

CIA Implements Controversial Detention and Interrogation Program

Barack Obama: The Global War on Terror

Drone Strike Assassinates U.S. Citizen

Donald Trump: Focus on “Radical Islamic Terrorism”

Trump Signs Contested Travel Ban

Joe Biden’s Policies Include a New Strategy on: Countering Domestic Terrorism

Full withdrawal from Afghanistan