South Africa: Why Countries Acquire and Abandon Nuclear Bombs

Why did South Africa give up its nuclear weapons? In this historical case study, learn about the only country in the world to have developed and then dismantled its nuclear program.

Teaching Resources—Nuclear Proliferation: Nonproliferation (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

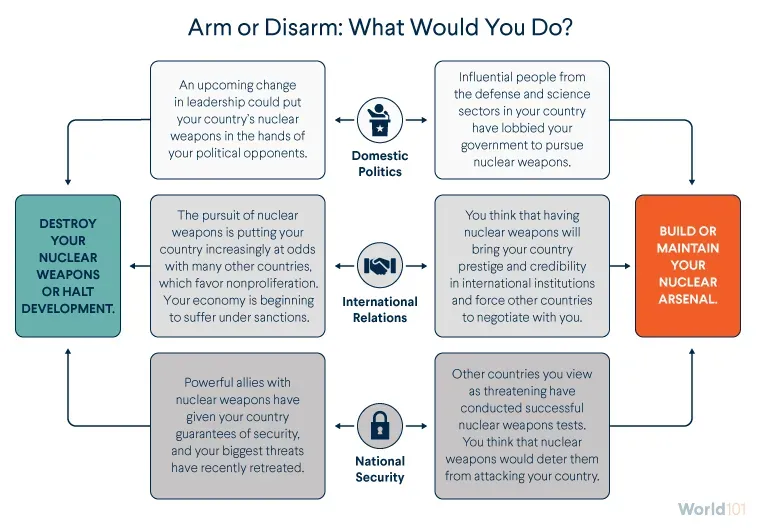

The decision to build a nuclear program is often shaped by a range of domestic and international economic and political factors:

- Domestic politics. Leaders who are contemplating a nuclear program weigh the political situation in their countries against desires of competing interest groups like scientists or defense contractors. Even the personal ambitions of political leaders can come into play.

- International relations. On the one hand, countries that possess nuclear weapons wield great influence with other countries; on the other, pursuing or possessing nuclear weapons can result in economic sanctions against a country. Becoming a pariah on the world stage is a concern for leaders who are considering a nuclear program, especially as countries are increasingly swearing off nuclear weapons.

- National security. Countries that feel threatened by their neighbors, especially those that are nuclear-armed, could consider starting a nuclear weapons program. The desire to intimidate rivals often tips the scales too.

The decision to build or destroy a nuclear weapons program can have life altering ramifications for citizens of one’s country and those living around the world.

Explore how leaders consider these issues in the following case:

South African Leaders Offer a Historical Case Study

South Africa is the only country in the world to have developed and then dismantled its nuclear program. The South African case offers insights into why leaders of a country would seek to acquire nuclear weapons and why they would give them up. Of course, South Africa armed and disarmed in secret, so its exact motivations can be difficult to determine. But declassified documents and official accounts help historians understand what drove the country’s leaders to pursue a nuclear program and then abandon it less than two decades later.

South African Nuclear Ambitions

Domestic Politics

In the late 1960s, the South African government began to explore a nuclear program for infrastructure projects, not weapons. Influential members of the nuclear power, military arms and equipment, and mining industries had a vested interest in such a program and likely convinced the country’s political leadership to pursue it.

South Africa was run at the time by the National Party, a conservative, anti-communist party that represented the interests of the ruling white minority known as Afrikaners. The National Party instituted apartheid, the system of institutionalized racial segregation in South Africa, which would ultimately make the country an international pariah.

International Relations

Initially, South Africa’s apartheid government maintained close ties abroad, including with the United States, which already had nuclear weapons. In fact, the United States helped build South Africa’s first nuclear reactor in 1965 and supplied it with highly enriched uranium, necessary for nuclear weapons. But South Africa was never a formal ally of the United States, which meant that U.S. support was limited. The South African government likely felt that having nuclear weapons would give it a more important role to play on the world stage.

When the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), the main treaty seeking to eliminate nuclear weapons, opened for signature in 1968, South Africa did not sign it. That decision was risky. During the 1970s, its system of apartheid and refusal to sign the NPT increasingly isolated South Africa. It couldn’t participate in the UN General Assembly, for example, which also encouraged member countries to sanction the country. The U.S. government suspended aid to South Africa and its athletes were even barred from participating in the Olympics and international cricket and rugby events. Yet that pressure did not curb South Africa’s nuclear ambitions. The country’s leaders at the time believed its international isolation was tied to apartheid, not its nuclear program. They thought that nuclear weapons would protect the country from security threats, not extend its exile.

National Security

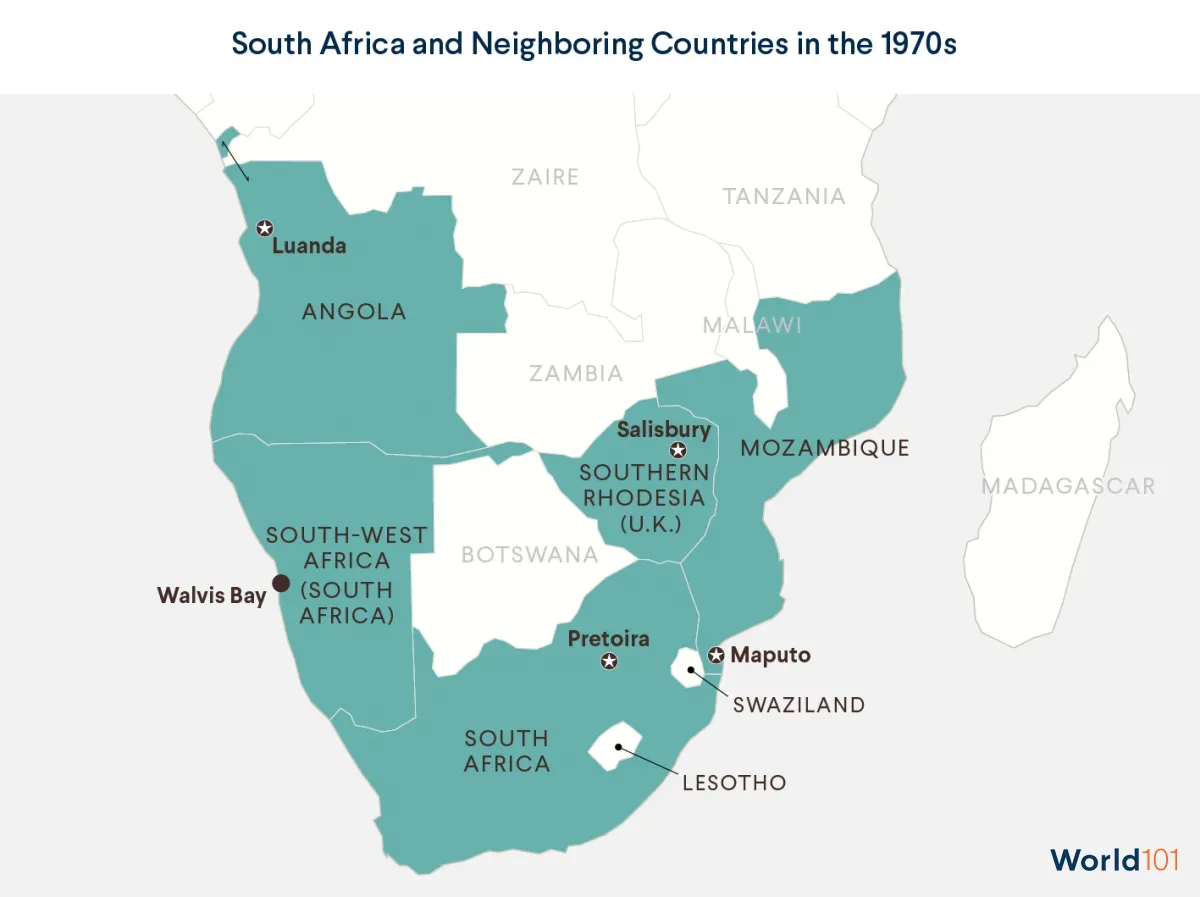

Government accounts claim that South Africa pursued nuclear weapons, at least in part, to counter security threats from its neighbors. Mozambique and Angola had gained independence from Portugal in 1975. Almost immediately, both countries became embroiled in domestic conflicts involving communist forces backed by the Soviet Union. Another neighbor, modern-day Zimbabwe, was also on the verge of independence, and the racist and anti-communist apartheid government feared imminent encirclement by Black communist nations. Desperate to deter against that perceived threat, South African leaders bet on nuclear weapons.

Why did South Africa give up its nuclear weapons?

In 1991, South Africa shut down its nuclear test site and uranium enrichment facility. Afterward, it joined the NPT as a nonnuclear country. On March 24, 1993, in a speech to the South African parliament, President F. W. de Klerk announced publicly that his country had secretly built and dismantled six nuclear weapons.

After weighing the options, assuming the risks, and putting in the time and resources to acquire nuclear weapons, South Africa gave them up. Why?

South African Denuclearization

Domestic Politics

President F. W. de Klerk assumed power in South Africa in September 1989, a time of domestic political unrest and uncertainty. Led by Nelson Mandela, the African National Congress (ANC) had built up strong domestic and international support for its opposition to the apartheid policies of the ruling National Party, of which de Klerk was a member.

De Klerk quickly ordered a report exploring the possibility of disarmament. The timing suggests the apartheid government feared that the ANC’s popularity could soon put nuclear weapons in the hands of a democratic Black government, one which de Klerk’s National Party had repressed and opposed for decades. The ANC’s connection to communism also stoked fear among South African leaders of a possible transfer of nuclear weapons to other countries or organizations hostile to South Africa, such as Cuba, Iran, Libya, or the Palestine Liberation Organization.

International Relations

Threats from the United Nations could have driven South Africa to acquire the bomb, but the promise of international reintegration and influence played a large part in the apartheid government’s decision to give up its nuclear weapons.

As more countries joined the NPT, South African leaders embraced the potential benefits of joining the treaty, which included the rehabilitation of its international reputation. Rehabilitation didn’t just mean getting on the same page as most countries. It meant participating in international sporting events and the global economy, from which South Africa had been isolated. Apartheid South Africa had been barred from participating in the Olympics, as well as major international competitions like the football and rugby world cups. At the same time, European countries had imposed trade sanctions, the world’s major oil producers established an oil embargo, and major financial institutions in the United States and Japan refused to do business in South Africa.

In 1991, South Africa officially ended its policy of apartheid. That same year, it joined the NPT as a nonnuclear country.

National Security

The late 1980s and early 1990s were an era of massive political change as communist governments around the world, including the Soviet Union, fell. The conflict in Angola, where South Africa had sent troops, ended in 1988.

As active regional conflicts subsided and the Soviet Union dissolved, South Africa’s government felt less vulnerable. The diminished threats, both regionally and internationally, played a large part in South Africa’s decision to disarm.

Historical cases inform future nuclear policy.

As this chapter of South African history illustrates, the decisions to acquire and give up nuclear weapons are not simple: they are informed by domestic and international issues and threats, both real and perceived. Looking critically at the decisions South African leaders made during that time can reveal what could cause a country to acquire nuclear weapons and what might persuade countries with nuclear aspirations to reverse course.