Teaching Resources—Migration: Introduction (including lesson plan with slides)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

More than 280 million people—roughly one out of every thirty people on earth—currently live in a country in which they were not born. With more people than ever on the move, it’s important to understand what drives migration because it’s increasingly likely that people will encounter—or become—migrants in their lifetime.

People move for a lot of reasons, which are often called push and pull factors. Some people are pushed to leave their countries because of conflict, natural disasters, or persecution. The conflicts ongoing in Ukraine and Syria, for example, have displaced millions of people. The majority of migrants, however, are pulled to countries that offer better economic prospects for themselves or their families. It’s quite common that a mix of push and pull factors affects a person’s decision to migrate.

In the past thirty years, the number of international migrants rose by over 80 percent.

In 1990, migrants represented 2.88 percent of the global population. Since 2005, the number of international migrants has shot up. In 2000, that percentage fell slightly to 2.82 percent, but in the winter of 2020 before COVID-19 restrictions set in, it rose again to 3.6 percent. People are far more likely to be international migrants today than in the recent past.

Much of this increase can be simply attributed to the growth of the global population in general. Major, enduring conflicts such as the Syrian civil war have also contributed to the rising numbers of migrants in the twenty-first century. And while the middle of 2020 saw a halting of migration the following years have seen migration trends reignite.

Where do migrants come from?

About one-third of all international migrants come from just ten countries.

However, numbers alone don’t tell the whole story:

- India is the top country of origin for migrants, with more than seventeen million Indian-born people living in foreign countries. Although Indian migrants are the largest group coming from a single country, they represent only 1 percent of India’s total population.

- Small countries can be dramatically affected by push and pull factors causing migration. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, violent conflict during the 1990s and lingering instability in the region since then has pushed much of the population abroad: in 2019, approximately 50 percent of the 3.3 million people born in Bosnia and Herzegovina lived elsewhere. Similarly, job opportunities and other factors have pulled around 10 percent of the Philippine population abroad. Emigrations of that size have profoundly affected the economies of these countries.

Where do migrants live?

In 2020, two-thirds of all migrants lived in just twenty countries. While this has been true for the past twenty years, the share of all international migrants living in these 20 countries has decreased, meaning more people are migrating to a larger variety of countries.

High-income nations hosted a majority of international migrants. That’s not surprising considering that a vast majority of the world’s international migrants are economic migrants who have voluntarily left their countries for better economic opportunities elsewhere.

Many refugees and asylum seekers, who make up just over 10 percent of the world’s international migrants, reside in developing countries or ones near those that they left. However, as we’ll see below, most asylum seekers ultimately apply for asylum in higher-income countries for similar economic reasons.

Among these nations, one stands out as the top destination for international migrants: nearly one-fifth of all international migrants currently reside in the United States.

Why are people migrating?

Where people migrate depends on what’s happening in the world. The countries that host large numbers of migrants change in response to the same push and pull factors that lead to migration: economic and political developments, as well as conflict, persecution, natural disasters, and other crises.

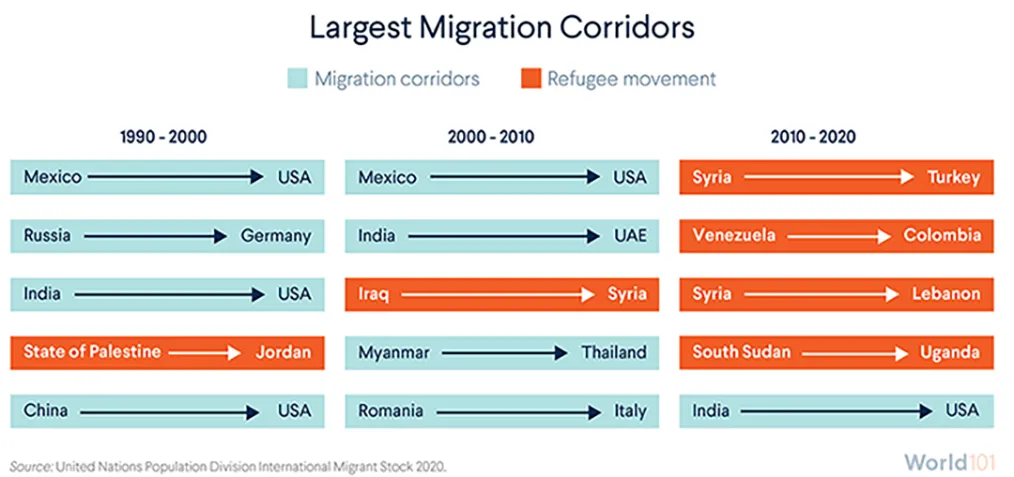

From 2010 to 2020, the four largest migration flows between two countries (also called bilateral corridors) were driven by refugee movements, fueled largely by the civil war in Syria. This is a change from previous decades, when the largest migration corridors consisted mainly of economic migrants looking for better work opportunities abroad.

Displaced people are driving migration today.

Humanitarian crises around the world have caused an increase in the numbers of displaced persons in the twenty-first century. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that by the end of 2022, over 100 million people were forcibly displaced. This means that more than 1 in every 74 people have been forcibly displaced.

The world’s refugee population is at a record high. The UNHCR estimates that there are over thirty-five million refugees as of 2022 (including Palestinian refugees under UNRWA's mandate). Syrians, Palestinians, and Afghans account for more than half of all refugees.

For the most part, refugees end up in countries near those that they fled.

At the end of 2022, low and middle income countries were home to approximately 76 percent of the world’s refugees and other displaced people. For example, as a result of the civil war in Syria, neighboring Turkey currently hosts the world’s largest refugee population of 3.6 million refugees. Sometimes these refugees live in temporary refugee camps run by host governments or the UNHCR; often they strike out on their own. Around 80 percent of refugees live outside camps.

High-income countries receive the most asylum claims from refugees.

Although a majority of refugees live in developing countries, three of the top five destinations for asylum seekers in 2021 were high-income countries, which offer better economic prospects. The United States alone received an estimated 188,900 claims that year—the most of any country.

What is the future of migration?

Migration—who migrates, where, and why—is constantly evolving. For instance, experts estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic reduced migration rates by 27 percent in the first half of 2020. Today’s migration patterns can tell a lot about the broader global context, from economic opportunities to humanitarian crises. But they also give a preview of what the future will look like in a world shaped by the paths of migrants.