Understanding the Last Fifty Years of Global Development

Has life gotten better for people around the world? Learn how improvements in health, education, and income are measured and explore three countries' opportunities and challenges with development.

Humans are living longer, literacy rates are up, and the world is, in many ways, a healthier and wealthier place. In China alone, more than eight hundred million people have left conditions of poverty over the past 40 years thanks to their country’s rapid development, and extreme poverty rates are declining worldwide.

But development is more than just lower rates of poverty and not everyone in the world is benefitting from development equally.

UN Definitions of Development

Development deals with the overall well-being of people in a given country. But what exactly does someone need to live well? Is a steady income enough, or does someone need other things, such as access to education and health care? Can a country be considered developed if some of its citizens fare much better than many others? Because there are no clear answers to these complex questions, there is no single definition of development.

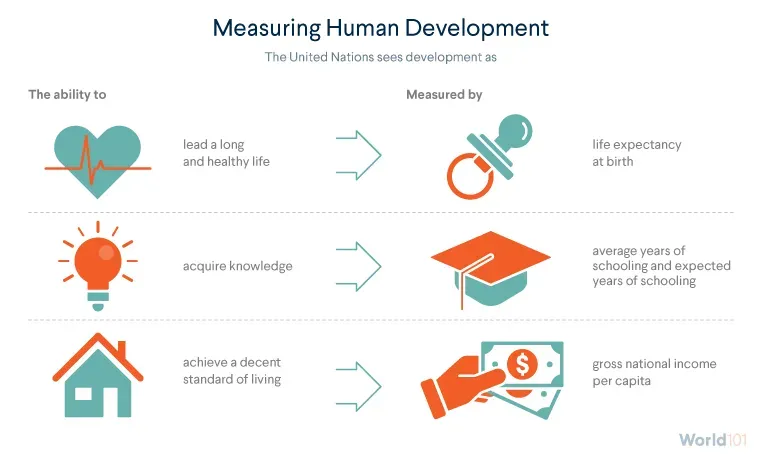

Nonetheless, some of the world’s leading institutions, such as the United Nations, have taken up the task of defining development. The UN Development Program (UNDP), a UN agency tasked with helping countries achieve sustainable development, works with countries to reduce poverty and inequality. Here’s how the UNDP defines and measures development:

By many measures of development, it would appear that everything is improving. The world today is generally a healthier, better educated, and wealthier place than it was fifty years ago.

But these trends do not tell the whole story. While these measures of global development are, on average, improving, not all countries are improving. In some cases, economic or social progress has stalled or even moved backward as a result of wars or crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. And even in countries that have experienced major advancements, everyone has benefited equally.

According to the United Nations, more than three-quarters of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs) - or the countries that are most underdeveloped - are in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. A majority of the world’s poor live in either of these regions, although they are home to only 40 percent of the world’s total population.

Just as extreme inequality can exist between regions, extreme inequality can also exist between countries in the same region. Twenty of the world’s twenty-five poorest countries are in sub-Saharan Africa. But some countries in the southern part of the region, such as South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia, have a higher gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, or per person than countries in the northern part, near the Sahara.

Similarly, inequality can exist within countries, just as it does between them. South Africa has one of the largest economies and among the highest GDP per capita in its region, but it is also one of the most unequal countries there. Meanwhile, the United States, the world’s largest economy, has higher income and wealth inequality than nearly any other developed country. Just because a country has high GDP or GDP per capita does not mean that the wealth is shared equitably among its citizens.

What Causes Development to Improve or Regress?

It can be difficult to determine why some regions and countries have developed faster than others. Many factors contribute to economic, social, and institutional flourishing.

To get a sense of factors that drive or hold back to development, it’s helpful to look at both developed and developing countries as case studies.

Singapore’s foreign trade and investment

Between 1965 and 2023, Singapore went from a newly independent country with scarce natural resources and a GDP per capita of $517 to a major global economy with a GDP per capita of $915,000, just ahead of the United States. Much of this success has been attributed to Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, who combined economic modernization and authoritarian governance to welcome foreign trade and investment and establish a strong rule of law. Singapore also focused on developing its people by investing in education. Since 1980, literacy rates have risen from 83 percent to 97 percent, and life expectancy has grown from seventy-two years to eighty-four years.

Haiti’s foreign debt

Few countries have had as much trouble with development as Haiti, the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. A large part of this is due to the country’s history. After two centuries of colonization, Haitians revolted against the French and achieved independence. But the 1804 independence agreement with France came with a major cost; Haiti was internationally isolated and made to pay reparations for more than a hundred years to France for the loss of its colony—the equivalent of $20 billion today. This foreign debt severely set back the young country’s economy, and, at times, foreign powers controlled Haiti’s finances. In 1915, the United States, concerned with protecting its economic and political interests in Haiti, invaded the country, rewrote Haiti’s constitution to allow foreigners to own land, and moved Haiti’s financial reserves to the United States. The occupation lasted nineteen years.

More recently, internal political instability and social unrest has spooked potential investors and has continued to hold back development and investment. Natural disasters like the 2010 and 2021 earthquakes destroyed crucial infrastructure. Multiple epidemics and mismanagement of humanitarian aid from NGOs further complicate matters in the country.

Syria’s civil war

Development also doesn’t just go in one direction. A breakdown in the rule of law or a lasting, devastating conflict can hold back or even reverse development. Since 2011, Syria has been embroiled in a destructive civil war, which some experts estimate has claimed over half a million lives. It has also forced nearly six million people to flee the country and more than six million others to suffer internal displacement. A significant amount of physical infrastructure—such as roads and hospitals—has also been destroyed in the fighting. Beyond the loss of life and human suffering, the result has been catastrophic to the Syrian economy: Beyond the loss of life and human suffering, the result has been catastrophic to the Syrian economy: between 2010 and 2020, the country’s economy shrank by more than half. While the war was preceded by decades of authoritarian rule which hindered the country’s the economy, the ongoing conflict and earthquake in 2023 has set back the country’s development even further.

What is the future of development?

History, natural resources, demographics, governance, geopolitics, conflict, and climate can drive—or hold back—development. People generally want their countries, and even other countries, to develop. But as these case studies illustrate, though there are recommended policies, there is no clear road map.