The Sustainable Development Goals

In this free SDG resource, learn about the formation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and review the opportunities and challenges for meeting them.

The world faces more interconnected challenges than ever before, shaped by new and evolving economic, environmental, political, and social dynamics. In an effort to encourage global cooperation, countries have convened over the last several decades to set targets for a more peaceful, prosperous and sustainable future.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the latest broadly agreed upon approach that supports countries to work together to set goals and measure progress for global development. Emerging in 2015 and building on the initial Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) first established in 2000, the SDGs aim to build a "shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future." They establish seventeen goal areas with targets countries wish to achieve by 2030, vastly expanding an initial set of eight goals set out in the MDGs. The seventeen goals cover everything from gender equality, reducing poverty, improving education, responding to climate change, promoting peace, and more.

The SDGs are ambitious, and in order to achieve these goals, substantial investment and change will be needed in both developed and developing countries. Collaboration across and within countries is required for progress, and many challenges remain. Still, the SDGs continue to serve as a guidepost that shapes flows of international development finance, major international dialogues, and political decisions in many countries around the world. After their "midpoint" in 2023, now is an apt time to review what's been accomplished via the SDGs and what remains to be done.

History of the SDGs

In 2015, UN member states adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the current framework the UN uses to monitor progress on development. However, the foundation of the SDGs began well before 2015. In September 2000, world leaders gathered in New York to decide the United Nations’ goals for the new millennium. From this gathering came the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), eight priorities for the first fifteen years of the third millennium, and the precursors to the SDGs.

The MDGs focused on basic objectives such as bringing people out of extreme poverty (then defined as living on less than $1.25 per day). And because problems such as extreme poverty disproportionately affect the world’s least-developed countries, the MDGs mainly focused on development in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

On paper, countries successfully met the MDG targets: From 2000 to 2015, the world experienced rapid development. One billion people rose out of extreme poverty, and global gross domestic product (GDP) more than doubled.

However, that does not mean that the world has finished developing, or that the development driven by the MDGs was felt equally everywhere.

Much of the progress made toward the MDGs happened in just two countries: China and India. They have the world's two largest populations and were long home to more poor people than anywhere else. Between 2000 and 2015, approximately three hundred million people in China emerged out of extreme poverty. But many of the methods used to achieve this goal afforded Chinese citizens few individual rights and, notably, had severe environmental consequences. For example, the Chinese government encouraged factories to increase the production of goods for export, and many farmers moved to cities for work. More coal-powered factories intensified air pollution and worsened air quality, and weak environmental laws did no prohibit pollution in waterways, contributing to longstanding environmental degradation despite these practices economic benefits at the time.

In India, too, over three hundred million people rose out of extreme poverty during the same period and the country’s GDP quadrupled between 2000 and 2015. But although India succeeded in eliminating extreme poverty, it had moved hundreds of millions of people just above the extreme poverty threshold with few savings, and major growth benefited different economic classes of people unequally.

Why were the SDGs created?

When the United Nations convened in 2015, identifying sustainable ways to develop was a top priority. The United Nations came up with a new development framework to address the shortcomings of the MDGs: the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Three main characteristics distinguish the SDGs from the MDGs: sustainability, interconnectedness, and a global focus. On January 1, 2016, the SDGs officially came into effect.

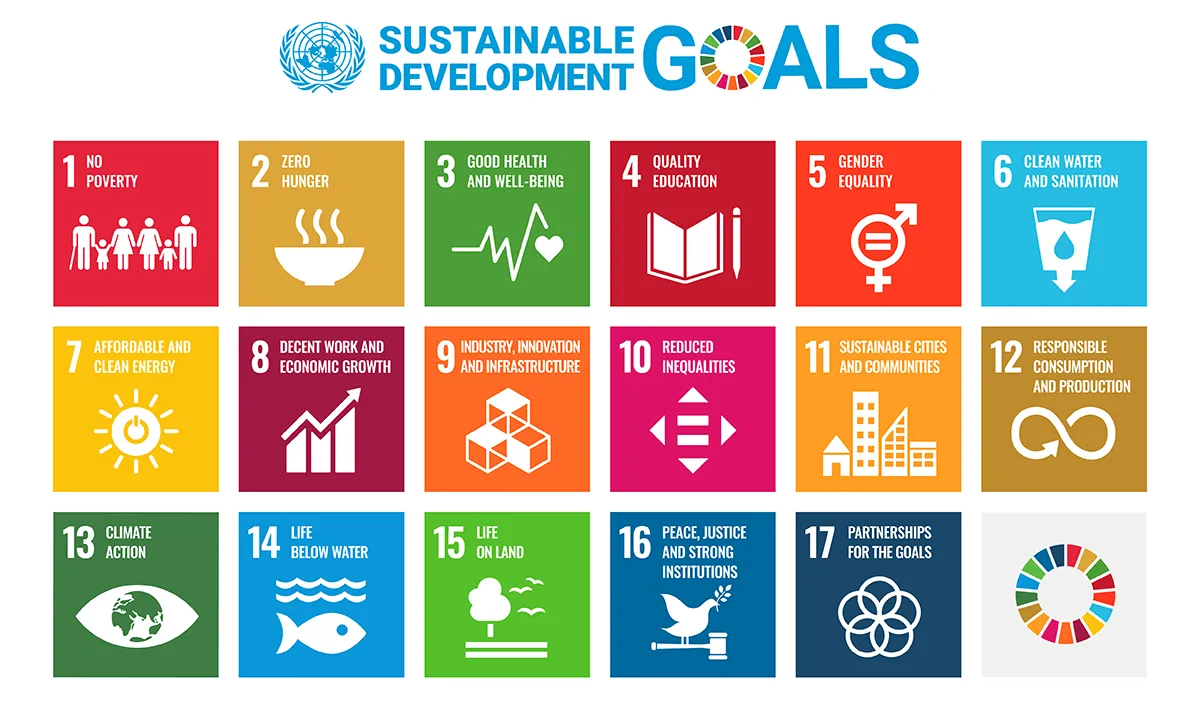

What are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals?

The seventeen goals set out in the SDGs are the following, each accompanied by their own sub-priorities, agendas, and metrics.

- No poverty

- Zero hunger

- Good health and well-being

- Quality education

- Gender equality

- Clean water and sanitation

- Affordable and clean energy

- Decent work and economic growth

- Industry, innovation, and infrastructure

- Reduced inequalities

- Sustainable cities and communities

- Responsible consumption and production

- Climate action

- Life below water

- Life on land

- Peace, justice, and strong institutions

- Partnerships for these goals

The SDGs focus on sustainability.

It is no longer considered enough to improve people’s livelihoods regardless of the environmental cost. The SDGs encourage countries to find environmentally friendly methods of development, such as by powering factories with renewable energy rather than by exclusively exploiting fossil fuels, which contribute to climate change. Each development project has to account for its environmental impact: how it would affect life on land, ensure a clean water supply, and respond to climate change.

The SDGs are also economically sustainable in that they promote inclusive growth. An overall increase in a country’s wealth is a worthwhile goal, but the SDGs ask these questions: Who benefits, and is the average person in a country gaining from the growth, or are just a few wealthy people reaping all the rewards? The SDGs push for programs that specifically target marginalized social groups, which often include women, ethnic and racial minorities, and people with disabilities. To be considered sustainable, development projects need to ensure equal opportunities for growth and eliminate discriminatory practices.

The SDGs are interconnected.

Rather than look at poverty in isolation, the SDGs focus on how improvements in one area can help others. For example, one way to improve gender equality is to install solar-powered street lights that stay on all night so that women feel safer walking home later in the evening, a strategy used to support women in rural Lebanon. This small, environmentally friendly step has a ripple effect: Women who are able to extend their hours of activity outside the house past sunset have more opportunities to take night classes at university and improve their educational attainment. They can also work more flexible hours and avail themselves of new job opportunities. Programs that address inequalities end up helping everyone: the more citizens who are able to work, the larger an economy can grow.

Instances of these interconnected methods can be seen in many places, and they often focus on environmentally sustainable methods of growth. In 2018, Peru’s environment ministry kicked off a project to combat the issue of giant garbage dumps and landfills that dominate the cityscape of Peru’s second-most populous city, Arequipa. The strategy included setting up teams of volunteers who promoted recycling through grassroots initiatives such as door-knocking in order to reduce the size of the landfills. These volunteers, mostly women from impoverished backgrounds, sorted trash and recyclable material in the landfills and sold crafts made from the recycled materials they collected. This program did not simply address the problem of expanding landfills; it did so in an environmentally friendly way, much more so than burning trash that releases greenhouse gases. One initiative can encourage progress toward a whole host of SDGs, including gender equality, work opportunities, responsible consumption and production, and a reduction in poverty.

The SDGs have a global focus.

With the creation of the SDGs, the United Nations recognized that it’s not just developing countries that need work; developed countries, too, face gender inequality, high income inequality, pollution, and other problems.

In Germany, hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, was banned in 2016 after years of debate. While fracking today is a cheap and easy means of extracting oil and natural gas, scientists warn that it poses serious risks to the environment. Ultimately, German politicians decided that environmental sustainability doesn’t have to be a trade-off for economic growth, a core principle of the SDGs. In the long term, it’s cheaper to invest in renewable energy than to deal with the public health burden and environmental damage caused by fracking.

In the United States, some municipalities are trying to combat income inequality, which is higher in the United States than in most other developed countries. For example, in 2015, officials in Emeryville, California, decided to gradually raise the minimum wage to $16 per hour by 2020. This change set off a ripple effect: higher wages mean workers don’t need to hold down two or three jobs to make ends meet. This means they are more likely to stop smoking (a habit highly correlated with stress), can afford to eat healthier rather than rely on fast food, and are able to see a doctor early on if they need to, rather than wait until health issues become serious. In the long term, these health outcomes can reduce strain on the U.S. health-care system as a whole. Studies indicate that a $15 per hour minimum wage across the United States would lower rates of child abuse, teen pregnancy, and teen alcoholism.

SDGs at the Midpoint

As the world reaches the halfway point to the 2030 set completion date for the SDGs, many challenges remain. Progress varies significantly depending on the goal. And in about one third of the target areas, progress is showing no change or even lagging behind earlier progress.

While progress in terms of achieving goals is slow, countries are getting better at monitoring their SDG outcomes. Countries' national statistics offices are partnering with stakeholders in international NGOs, academia, and the private sector to improve data coverage and monitoring coordination. Data is crucial to knowing if countries are on trajectories to meet the SDGs, and in helping them stay on course.

Will the SDGs succeed?

The SDGs make clear that improving development cannot come at the cost of serious environmental harm and economic inequality. And unlike the MDGs, the SDGs focus on improved living conditions in both developed and developing countries. But to truly succeed where the MDGs fell short, the SDGs will require countries to collaborate on projects beyond their borders.

For example, Angola, Namibia, and South Africa all share the Benguela ecosystem on the coast of southwest Africa, an area on the coast of southwest Africa rich in biodiversity and marine life. This ecosystem has been damaged by overfishing, marine transport, mining, and pollution. The decrease in the availability of fish has hurt fishers in all three countries who depend on healthy marine life for their livelihoods. Realizing that overfishing and pollution are not simply domestic issues, officials from Angola, Namibia, and South Africa agreed in 2001 to collectively promote sustainable development in the area. In 2007, the countries created an intergovernmental organization, the Benguela Current Commission, that continues this work today.

Because these countries cooperated to achieve a shared goal, their local economies and environments all receive the benefits of sustainable development. This type of cooperation is essential to achieving the SDGs because global challenges don’t stop at one country’s borders and neither can the responses.