The Inflation Reduction Act

What is the IRA? In this free resource, learn what the United States' largest-ever climate change legislation does.

Teaching Resources—Climate Change: Actions (including lesson plan)

Higher Education Discussion Guide

What is the Inflation Reduction Act?

On a hot June day in 1988, NASA scientist James Hansen testified before the U.S. Congress that the earth’s climate was changing. Greenhouse gases from human activities were causing global temperatures to rise, which would likely lead to higher sea levels and an increased risk of extreme events like heat waves.

Over the next couple of decades, scientists continued to warn that those effects would potentially incur enormous economic costs and that they threatened the well-being of millions of people in the United States and around the world. And with that startling information, to prevent the harms of climate change, Congress did—well, not much. At least until the summer of 2022, when it passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

More than three decades after Hansen’s testimony, President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law. That far-reaching bill makes significant changes to U.S. tax policy and healthcare costs, but most important, it’s the United States’ largest-ever investment in addressing climate change—to the tune of around $370 billion over the course of ten years.

The bulk of those billions goes toward mitigation efforts to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change. Those efforts can largely be broken up into three broad approaches:

- ensuring the United States has the knowledge and resources necessary to develop more clean energy and manufacture more electric vehicles

- encouraging U.S. industries and businesses across the economy to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

- encouraging individuals to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by improving the energy efficiency of their homes and driving cleaner vehicles

The IRA also funds some adaptation measures to prepare the country to face climate change’s effects. For example, it supports programs that would help protect forests from wildfires and plant trees in urban areas, which can provide shade and lower temperatures for city dwellers. Additionally, parts of the bill specifically target funding at both disadvantaged and rural communities to ensure that climate adaptation and mitigation projects aid them directly.

Look here for a deeper dive into the different policies and programs in the IRA:

Inflation Reduction Act Policy Highlights

Why is the government spending money on all of those programs? Why can’t the government just make a rule saying that everyone must stop emitting greenhouse gases? It’s not so simple. The U.S. economy relies on fossil fuels—with around 80 percent of U.S. energy consumption and production coming from coal, oil, and natural gas.

Replacing that much energy infrastructure requires time and an enormous amount of financial and physical resources. For now, banning fossil fuels outright would create severe disruptions in everyone’s lives. But those costs alone shouldn’t stop efforts to reduce fossil fuel use because the pollution and climate change they cause generate significant health and economic costs as well.

The U.S. federal government recognizes both the harms of fossil fuels and the costs of transitioning away from them, and those considerations are reflected in its more measured greenhouse gas regulations. Instead of an outright fossil fuel ban (which is not considered a serious proposal by most policymakers), the U.S. government’s regulations currently focus more on limiting how much greenhouse gases new power plants and vehicles can emit, with the expectation that those cleaner power plants and vehicles will eventually replace the older, dirtier ones.

In addition to regulations, though, governments have other tools to fight climate change—like throwing money at the problem.

One way is to fund the research and development (R&D) of new emissions-reducing technologies and projects that the academic and private sectors haven’t fully funded for one reason or another. (Maybe the technology doesn’t seem commercially viable, or perhaps it requires an enormous amount of resources to develop.) Sometimes the projects won’t pan out, but other times they wildly succeed. For example, federal funding helped develop the Global Positioning System (GPS), the internet, supercomputers, and COVID vaccines.

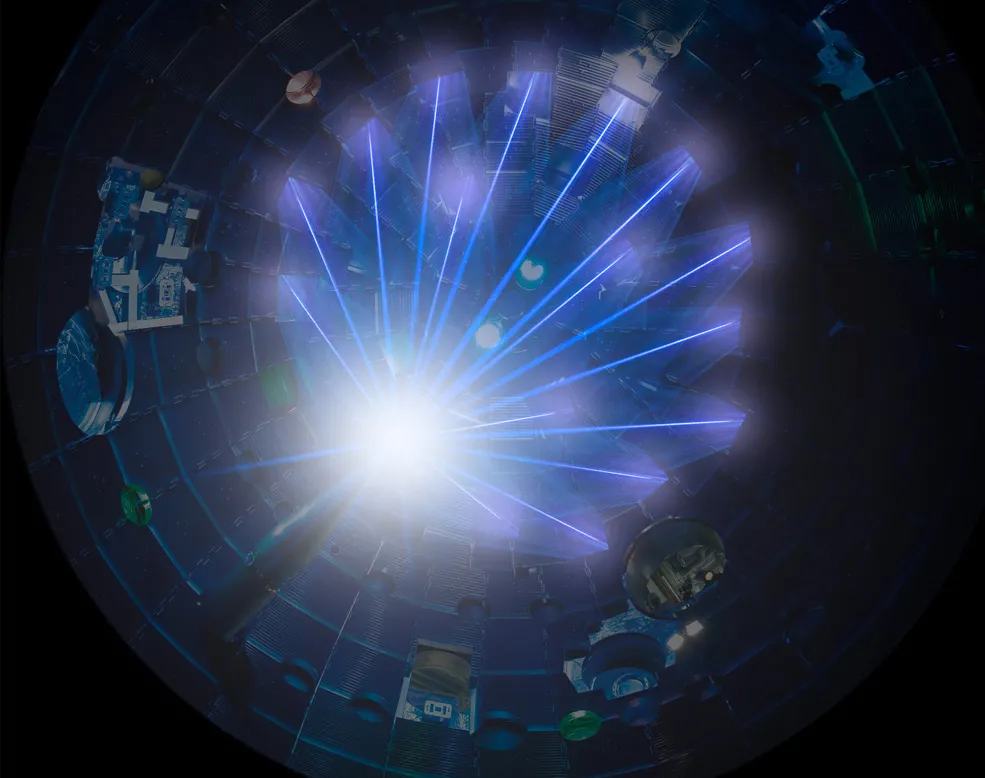

The IRA embraces that R&D approach, dedicating hundreds of millions of dollars to researching new types of energy generation, like nuclear fusion, which could greatly help to combat climate change.

The IRA isn’t just gambling on technological breakthroughs, though. It’s also spending billions of dollars to increase the development and adoption of already-viable clean technology like battery storage, clean hydrogen, electric vehicles, solar power, and wind power.

That spending takes various shapes, from tax credits and rebates to grants and loans, but the overall function, called a “subsidy,” is the same. The government is offering carrots—instead of sticks—to change behavior. To get that federal money, recipients—whether they’re local governments, private businesses, or individual consumers—need to take a specific climate mitigation or adaptation action.

While these direct changes in behavior are beneficial in their own right, there can be indirect benefits too. As the subsidies encourage more people to buy more climate friendly products and services, the businesses that provide those products and services are more likely to invest in better tools, new research, and greater production facilities. Those investments would then lead to the delivery of better and cheaper climate-friendly products and services, which could attract more business and new customers. This in turn, would justify additional investment, creating a virtuous cycle. Eventually, the markets for these products and services would grow to be self-sustaining at a large scale and able to function without the government subsidy.

While governments can spend money to encourage beneficial behavior, they can also raise money (via taxes and fees) in ways that disincentivize, or discourage, harmful behavior.

To mitigate climate change, dozens of countries have established carbon taxes, which are fees typically placed on producing certain products and activities based on how much carbon dioxide (CO2) they emit. Such fees encourage businesses to reduce their carbon footprint to avoid paying the tax. Some industries will respond by increasing the cost of those products and activities, which will make consumers less able to afford them. People will use those products and perform those activities to a lesser degree, thus reducing CO2 emissions.

Various groups have advocated that the United States establish a carbon tax; however, over the past couple of decades, attempts to pass a carbon tax have failed in the U.S. Congress, with opponents citing potential economic costs and unpopularity with the American public as factors.

CO2, though, isn’t the only greenhouse gas. One of the others is methane, on which the IRA placed a per-ton-emitted fee, establishing the U.S. government’s first-ever tax on a greenhouse gas. The tax is limited in scope, only applying to certain facilities in the oil and gas industry. Nevertheless, it’s a milestone in U.S. environmental policy.

Expected Effects of the IRA

To mitigate climate change, dozens of countries have established carbon taxes, which are fees typically placed on producing certain products and activities based on how much carbon dioxide (CO2) they emit. Such fees encourage businesses to reduce their carbon footprint to avoid paying the tax. Some industries will respond by increasing the cost of those products and activities, which will make consumers less able to afford them. People will use those products and perform those activities to a lesser degree, thus reducing CO2 emissions.

Although the IRA alone won’t satisfy the U.S. pledge, some experts say it helps restore U.S. credibility on climate change. In the prior administration, President Donald Trump had pulled the United States out of the Paris Agreement and rolled back U.S. climate regulations, but Biden had the United States rejoin the Paris Agreement and is pushing forward new, far-reaching climate mitigation policies. So now, the United States will likely be better able to convince other countries to meet their own emissions-reduction pledges—which could allow the United States to retake a leading role in coordinating new international efforts against climate change.